The Assay Interview Project: A. Kendra Greene

April 25, 2022

|

A. Kendra Greene began her museum career marrying text to the exhibition wall, painstakingly, character by character, each vinyl letter trembling at the point of a bonefolder. She became an essayist during a Fulbright grant in South Korea, finished her MFA at the University of Iowa as a Jacob K. Javits Fellow, and then convinced the Dallas Museum of Art they needed a Writer in Residence. Of late, she is a Visiting Artist at the Nasher Sculpture Center and a Library Innovation Lab Fellow at Harvard University.

|

|

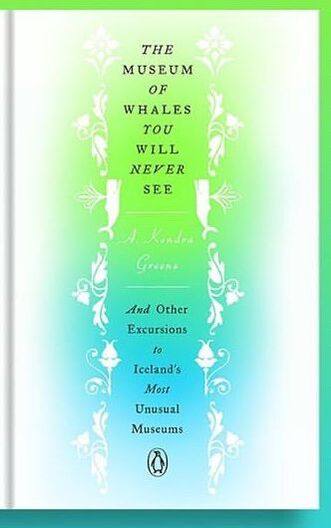

About The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: And Other Excursions to Iceland’s Most Unusual Museums: Iceland is home to only 330,000 people but more than 265 museums and public collections. They range from the intensely physical, like the Icelandic Phallological Museum, which collects the penises of every mammal known to exist in Iceland, to the vaporously metaphysical, like the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft, which poses a particularly Icelandic problem: How to display what can’t be seen?

In The Museum of Whales You Will Never See, A. Kendra Greene is our wise and whimsical guide through this cabinet of curiosities, showing us, in dreamlike anecdotes and more than thirty charming illustrations, how a seemingly random assortment of objects–a stuffed whooper swan, a rubber boot, a shard of obsidian, a chastity belt for rams–can map a people’s past and future, their fears and obsessions. “The world is chockablock with untold wonders,” she writes, “there for the taking, ready to be uncovered at any moment, if only we keep our eyes open.” Emily Danker-Feldman: In The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: And Other Excursions to Iceland’s Most Unusual Museums, you explore the stories of seven galleries among the more than 265 museums and public collections in a nation with the population of Lexington, Kentucky. You visit penises and stones, birds and “poor people’s stuff,” a lost Herring economy and an inadvertent witch memorial, sea monsters. Across that exploration, you play with expectation and imagination. There are points when you interpret something one way, only to learn it is decidedly not so, when charm is born of surprise or contradiction. “Maybe” and “Perhaps” ring out often, as do “I like to think” and “I imagine.” How did you come to incorporate so much of your own musings and fantasies into this book? Did that evolve or was it a more deliberate undertaking?

A. Kendra Greene: I find “maybe” and “perhaps” and the whole family of qualification and caveat represent a set of magic words for the essay. By getting you into the spaces that for any number of reasons can’t be fact checked, into anecdote and speculation and imagination, they grant access to the whole other half of human experience. Without them, you miss too much. I think I came to live with them in the first place because I was looking for the scrupulous language to get things right. There’s all the uncertainty and ambiguity of trying to understand things at all, and then so much of what I’m interested in is too small or niche or temporary to definitively corroborate. But those moves to signal the edges of certainty also start to illuminate larger questions of what can be known and how we go about knowing it—and that’s really something. Insofar as this is a book about trying to make sense of a phenomenon, of the rapid and prodigious and really clever expanse of museums that have come into being these last 25 years, it’s a project of collecting facts into meaning. And I want to be transparent about not just what but how I’m figuring it out. As I got deeper into this project, I realized how I’m often not as interested in the ultimate truth of a story so much as the fact that the story is told. And, as long as we’re talking about qualifying language, can we add to these phrases of permission the sheer workhorse nimbleness of “they say”? Its simultaneous best-we-can-do accuracy and near total refusal of an actual attribution? At once hearsay and a truth that needs no author? Mere gossip and the kind of wisdom tested and tumbled down generations to aphoristic shine? I know it would get circled in red pen in a tradition like the research paper, but as a document of how we hold knowledge informally, it’s just stunning. What wasn’t, isn’t, or won’t be is just as important in this book as what is. There are items never collected, histories unknown, and paths untaken. The title is suggestive: this is about Whales You Will Never See—a museum you could go to but don’t, a gas station you can’t find. What did that negative space mean to you as you were writing this book? There are things that are too big, too intense, too painful to take on directly, and so, instead of staring at the sun, we have filters and pinholes and strategies to still witness the eclipse. Maybe it’s similar: There are things more defined, more knowable, by absence than presence. I love every kind of pause: I love a beat, a rest, a breath. I love a comma, obviously. I love that we need both the en-dash and the em-dash, the colon and the semi-colon; for that matter, the half-title and the dedication and the epigraph and the foreword and the page turn and the end paper and the blank page—so many technologies to represent precisely calibrated space, silence a language of its own. Rebecca Solnit writes about the space between frames in a film strip being what allows the eye to make the illusion of cinema come alive. We need gaps. What isn’t is part of what defines what is. In the book, I think this informs both form and content. I ask a lot of the section break, for instance. It supports pivots and makes connections and makes things land hard or gently. It multiplies the number of beginnings and endings in one essay, and it’s the only thing that makes sense when there are twelve things I kind of need you to know all at once. In subject terms, it’s one of the most striking things to me in museums: the fact that anything survives. The teacup dug up from deep below a farmer’s field by a family that figured out where a steamship sank when the Mississippi River had different borders—and the wear on the gilding on the lip shows that its owner was lefthanded. The Wari panel of blue and yellow macaw feathers from sometime around 650-850 CE in ceramic jars found by workers in Peru in 1943—the feathers, even now, intensely hued. That anything lasts at all is amazing, but that a particular thing is still here, right here, to behold—that it could be collected at all, much less kept, is just so unlikely. Everything that’s here to see echoes with so very much that isn’t. Loss and grief figure prominently in this book. There are losses of ways of being, many of which reflect losses of our natural environment. There are losses of people; two of the museums are born of a loved one’s death and many swell with the possessions of the deceased. You tell the story of Iceland itself as a story of loss, writing “Iceland trades in … every gradation of loss and lack and disappearance. It is a population that hovered near fifty thousand for centuries and centuries, that didn’t hit six digits until 1926, but that every so often is astonishingly diminished.” One museum guide says of the sparsely populated nation, “That is the incredible story: how anyone has survived at all.” What is it about loss and grief and museums that go hand in hand? I talk a lot about museums being storytelling institutions. If you are also an institution of collection and preservation—of persistent stories—of course you are also a site of memory and memorial. In 2020 the American Alliance of Museums was predicting a third of US museums would likely close due to the pandemic. In June of 2021 its survey was less dire (maybe 15% at risk) but still a reminder how even places that traffic in preservation are as vulnerable as anything else. That fragility also underscores how much we like to think of museums as permanent—we want something to be safe and sturdy. But museums are profoundly human places. They work at a kind of precipice, between past and future, active and passive, here and gone, known and unknown. A lot of what we know about those boundaries, those liminal spaces, we know from loss and grief, but I’d like to point out it doesn’t make them inherently sad or mournful. Pam Houston writes a lot about trauma and climate change. Recently, when I heard her interviewed, for almost two hours outdoors in a canyon, most of the conversation was about finding joy. She was saying grief is about love, that in the midst of so many sources of grief we need to remember how that pain points to what we love. I think that it’s easy to see how museums relate to loss and to grief because of the ways they connect to or express the bygone. But we’d be wise to see that, more than grief, at their core, museums are often about love. I wondered, as I was reading this book, about how you recorded and kept track of everything, especially your conversations and impressions. What was your process? Was anything lost along the way? A lot of my practice is waiting. Even a tiny museum has a café. You can be parked for days in a place most people have left in an hour. I came to recognize a kind of panic a few days in that I’d guessed wrong, that I couldn’t get at whatever had piqued my interest and this was all a huge waste of resources—and then some new and necessary thing would find me because I was still there, right where I needed to be. I take my field notes by hand. It can be a little slow-going when I need to transcribe a printed text or a number of museum labels, but mostly I’m recording pieces of oral history and trying to catch what strikes me or seems promising in a space. I like the transparency this has during an interview, that even if you can’t make out my handwriting upside down, you can see when I’m writing, that I’m writing. And to the extent it slows down the conversation—when I need to get two whole sentences exactly as uttered because it’s not the idea but the phrasing doing the work, or to be sure I have the spelling right so I can hope to research more later—I find slowing down, the care of that act, makes space for a conversation to find its depth. My second trip to Iceland for this project, I took an audio field recorder because I thought it would be responsible, professional, but ended up only capturing the stream tripping through the garden lot of the stone collection. I also collected. I have a whole shelf of museum brochures and guides and leaflets and maps and all stripes of museum ephemera. I remember measuring a two-month research trip by the waxing weight and waning space as my backpack filled with the books the museums themselves had made. Between 2011 and 2019 the camera technology improved so much that the text I started out copying down could eventually be photographed and still be legible, even down in the archives or in the dim chambers of the Sea Monster Museum. I didn’t start out thinking I was working on an illustrated text, but when the essays started appearing as chapbooks with Anomalous Press, when they weren’t just text but objects, I started leaning into what books get to do: custom end papers and half titles and maps and original art by Annie Nilsson and Fowzia Karimi. By the time I was working with Penguin, the seven trips’ worth of pictures were an important archive for everything from talking about the tone and palette of the cover to how I wanted to draw for the book. When the book arrived into a world just getting used to Zoom events, the pictures were one more way to transport readers to the landscape of this book, and going through them made me think a lot about how I had been photographing as a matter of reference and document, for myself, but there were ways to compose them into something public facing. The book is quite dense with information, but it doesn’t feel that way because of how you use generative storytelling as an entry point. We’re drawn into a narrative about a woman who got married and began bringing stones home. You ask us to imagine bringing something, anything, home, one every day. You tell us how you’ve seen her stones, one “clotting in the middle to the color of cream stirred into weak tea.” Then, suddenly, we’ve learned that Iceland has some 150 varieties of minerals, that Jasper is particularly common to the east, and that the remains of a deer who arrived before the Ice Age, possibly on a lost land bridge from Scotland, were found up in Vopnafjörður. Your storytelling, full of interesting characters and turns, laced with your poetic impressions and imagination, makes the density feel light. If you had to pick one thing, what, for you, makes a good story? Why? In ninth grade we took the Myers-Briggs personality inventory, and I remember this one question: All things being equal, is a story better if it’s true? I remember because it was something I had never given much thought to, and yet, I also knew the answer so instantly I was startled. I don’t know that there’s any one thing in isolation that makes a good story—it might always be a matter of chemistry and proportion. But if you can have all the things story can do—if you can have rhythm and resonance, surprise and satisfaction, if you can be made to imagine or empathize or wonder or care—if you can have that and also be given some insight into the world, some new working knowledge of the universe?! If you can know something new and that changes what you know to be possible and you get to grapple with that while all the bells are ringing? If you can have wonder? My god. What more could you hope for? What more could you want? There is so much poetry in this book. Too many phrases to pick one. You write of stories that are “unshakeable, like shadows” and watching the “perfect reflection” of eggs, how “their reflection inside the glass doubles and redoubles, the hollow shells reproduced, a line not quite straight but predictable, lifting up and back, to infinity.” What drove or sustained the poetry of this book? What force(s) kept you returning to that expansive place? It seems possible that Iceland itself is the expansive place: a place settled mostly on the shoreline, so much facing the eternal sea. The writing, perhaps, is only responding to what’s there. There are places in Iceland marked by lines of stone cairns. The cairns are very old, spaced so you could navigate the landscape even through thick mists. When you see them on a clear day, they’re not far apart at all. One summer, I was in Iceland for two weeks before the marine layer blew off long enough to see the sky. There are months at a time no one sees that blue or the sun itself. A place used to such big shifts in visibility, in daylight itself, a place that turns a precious flock of sheep to pasture away in the highlands for a whole season—it makes sense that such a place would shape your understanding of what exists even though it can’t be seen. Meanwhile, Iceland has funneled so much of its creative resources into literacy and literature, poetry and sagas, songs sung across valleys for one other shepherd to hear. If lyric springs from or soaks into a place, if that’s a thing, it’s had a thousand years to happen on that rock. But that’s all a bit speculative. Maybe it is as simple as I write very much like I speak, like I think, and this is just how I sound. Certainly I love conversation and oral history, and I know I’m ready to write when I can hear a line. So much of how we understand the world is through metaphor; we’re already tuned for the literal and the physical to carry the weight of symbol, to have both meanings happen at once. Which is maybe to say I think the poetry is the ends, not the means. I think it’s very possible it’s maybe just what you get when you are striving for accuracy. The world is so beautiful, so maddening, both so intensely concentrated and so ineffably diffuse that just to tell it like it is, to try to, that’s enough to risk poetry. It strikes me that there is a lover’s quest for essence in this book. Poetry and figurative language are shorthand for something deeper. A single anecdote lets you know who someone might be, who they are to you. A story about a fish or a bird, about a museum, lets an outsider peek inside the curtain of a culture. Of the Skógar Museum, with its driftwood and brass ring, you write: “Nothing makes me want to be an Icelander more than this museum.” You write of writing: “And of course what to leave out matters as much as what to include.” How did you go about capturing the essence of a nation that so captivated you? How did you decide what was important to say and what to leave out? I definitely set myself a much smaller task than capturing the essence of a nation. I mean, what an enormous responsibility that suggests—especially working in a language and a country not my own. Obviously I can’t have the authority of an Icelander when talking about Iceland, but where I have some insider status is with museums. So, a pretty niche question about the number and suddenness of a certain kind of institution in a singular small country caught my attention, and just trying to make sense of that proceeded to open all sorts of doors and lines of inquiry. Scratch at museums and you soon arrive at the people who make and sustain and shape them, people who have their curiosity and commitment and love on display. I’ve come to be really grateful for those two forces—both that place of grounding and familiarity that got me started and that place of encounter so amply full of reminders of why we ought to move with humility and generosity. There was a point maybe halfway through the project where I was looking at my field notes and I was very aware of all the details I had recorded but wasn’t using in the writing. I was concerned about the things I was pretty sure were written down nowhere else, things that for whatever reason would never be asked for or remembered or set down like that again. And I felt the weight of that. I saw how there was a path where I could write a dissertation on Icelandic Museum Creation: 1995-2015, and the data in my field notes, more of it anyway, might be available. But that wasn’t my aim. The essay doesn’t just collect facts, it arranges them, questions them, puts them in context like the setting for a gem. As I was realizing I should resist the urge to include everything, I was nonetheless still between research trips. I had used everything I needed from my field notes but didn’t want to lose momentum on the project. It became really instructive to see what needed to be done in that in-between space. The facts and the data and the research had felt so precious and hard won, I’d been focused on them. But as they became totally mined, I experienced how the essay lives in the analysis and the questioning and the trying to make sense that comes next. I think of writing very much as a form of conversation. The philosopher Paul Grice articulated the Cooperative Principle, which suggests in part that a good conversation partner says neither too much nor too little. We get frustrated by people who withhold, but we also struggle with those who inundate or distract or confuse us. The whole point in Grice’s framework is to be informative, truthful, relevant, and clear. I’m tempted to add delightful or astonishing to that list. Or maybe that’s already part of relevant? The way we need to witness together, to share the good stuff, the way we hope to move someone? I know in the writing I am very often trying to smuggle in a darling. If it’s something that I love, that I have to share, that I can’t get over, that I really just want you to know because it’s amazing—that’s a good sign it’s important to say. Emily Danker-Feldman has a passion for creative writing. She is a Supervising Attorney with the Midwest Innocence Project and Director of the Innocence Clinic at the University of Missouri School of Law.

For Further Reading |