ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

5.2

5.2

|

Live by analogy, I tell my creative nonfiction students. Not by dwelling in comparisons between unfamiliars, but by making their familiars strange. To find a draft essay’s architecture—its organic design—through the revision process, they should look to other arts. Because analogies reframe our creative uncertainties, tilt our stories awry, and resituate us beside them. Similarities between unrelated situations unfold, altering our perspectives and prompting new insights. Analogies offer distance from what we expect, know, or think we know. They provoke creative interference: producing raw ideas held in a state of potentiality, which provokes associative processing and reflection (Gabora and Saab). Most important, they are haptic: to activate an analogy’s simultaneity and surprise requires adaptive, sensorial, hands-on work. [1]

|

|

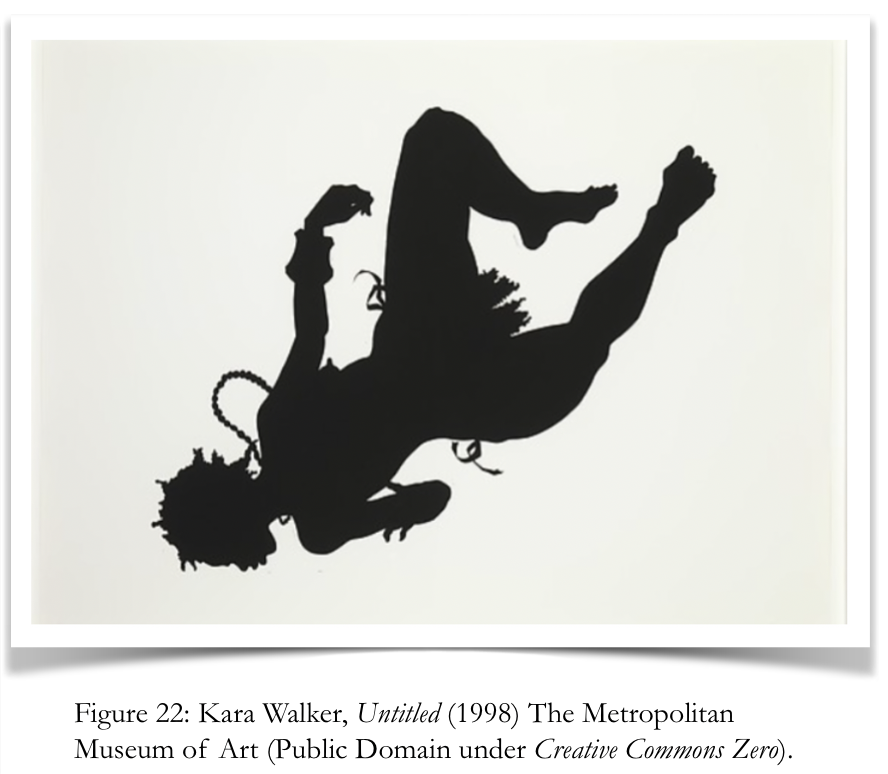

Shifting from marble to textiles, I offer paper cutting as a more practical applied art for the essayist. A brief slide show (from Étienne de Silhouette’s 18th-century shadow portraits to Kara Walker’s shocking wall-sized silhouettes critiquing U.S. racial politics) illustrates how Western paper cutters have variably crafted stories (through human profiles, historical scenes, and alternative lifescapes) in blunt contour.

|

To challenge students’ immediate or automatic ways of seeing, I focus on the well-known silhouette, Rubin’s Vase. A doubled image, it illustrates both the cut-out and hollow-cut silhouette methods that involve maneuver positive and negative space, a kind of internal and external contour at once. [5] And it invites them to look at a given subject from diverging vantage points.

What do you see in this silhouette? I ask them. The positive white space composing the vase? Or the two faces shaped by the negative white space between and around them? Or something else? A trick of the eye perhaps, but twice seen, we recognize the simultaneous figures. After this quick exercise, students adapt their essay’s contour drawing into a silhouette (using either the cut-out or hollow-cut method) and paste it into their writing journals. A revision exercise, the cut and pasted paper helps students to visualize how their essay’s organization (i.e. where details are foregrounded or sublimated) frames (or unframes) its situation and emerging story.

What do you see in this silhouette? I ask them. The positive white space composing the vase? Or the two faces shaped by the negative white space between and around them? Or something else? A trick of the eye perhaps, but twice seen, we recognize the simultaneous figures. After this quick exercise, students adapt their essay’s contour drawing into a silhouette (using either the cut-out or hollow-cut method) and paste it into their writing journals. A revision exercise, the cut and pasted paper helps students to visualize how their essay’s organization (i.e. where details are foregrounded or sublimated) frames (or unframes) its situation and emerging story.

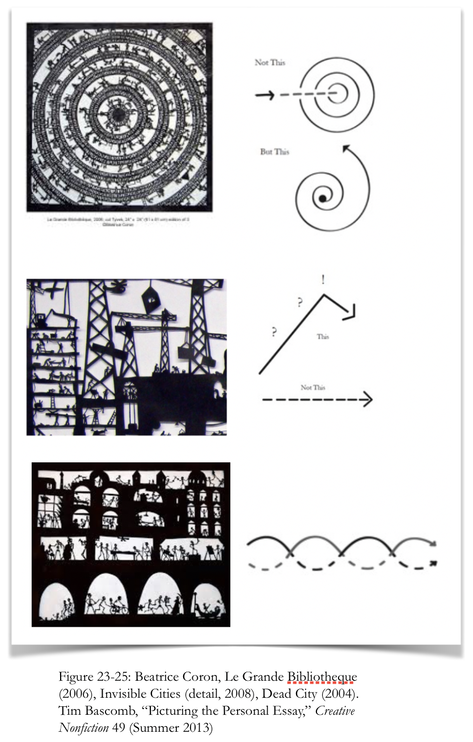

In the following class period, we watch contemporary French paper artist Beatrice Coron’s Ted Talk, “Stories Cut from Paper.” Taking a piece of paper or large DuPont™ Tyvek® (a paper-like product made from flash-spun, high-density polyethylene fibers), Coron typically begins her paper cut by visualizing her story. Sometime sketching, always sensing by hand, she intuits it shape: “By cutting paper, I look for hidden secrets behind the surface.” Through her unplanned process of discovery, Coron trusts the blank paper’s suspended potential, its thrill of anticipation and deferral of meaning. The story and its organic form are indwelling, “already inside the paper,” she explains. “I just have to remove what’s not from that story.” After cutting the story, Coron places the design on a contrasting background for “people to see what I see.” Framing and contextualizing the design—like a revising writer considering their audience--she makes the story clear-cut to its viewers.

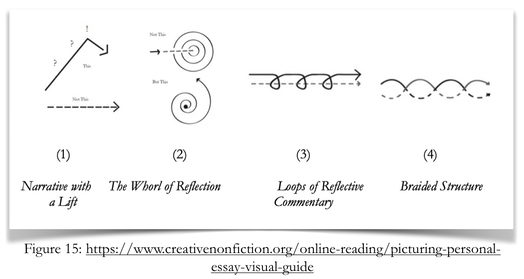

The paper-cutting analogy comes into starker relief by placing Coron’s paper cut-outs beside Bascomb’s earlier essay shapes:

The paper-cutting analogy comes into starker relief by placing Coron’s paper cut-outs beside Bascomb’s earlier essay shapes:

Coron’s urban architectural structures (from library and scaffolds to porticos and colonnades) illustrate the kinetic energy of narrative worlds. Of an essay’s paper architecture. Interactive geometries (of circles and squares and rectangles and rhombuses and parallelograms and trapezoids) transform negative into three-dimensional space. Peopled, these spaces invite us to join the black cut-outs animating the scenes. Tracing each essay’s contour, Bascomb similarly instructs his readers how to view the organic geometries: (This is how the story is shaped, not That). A kind of negative space, the not That resembles the silhouette’s cut-out. It is precisely where the writer-editor removed the extraneous words.

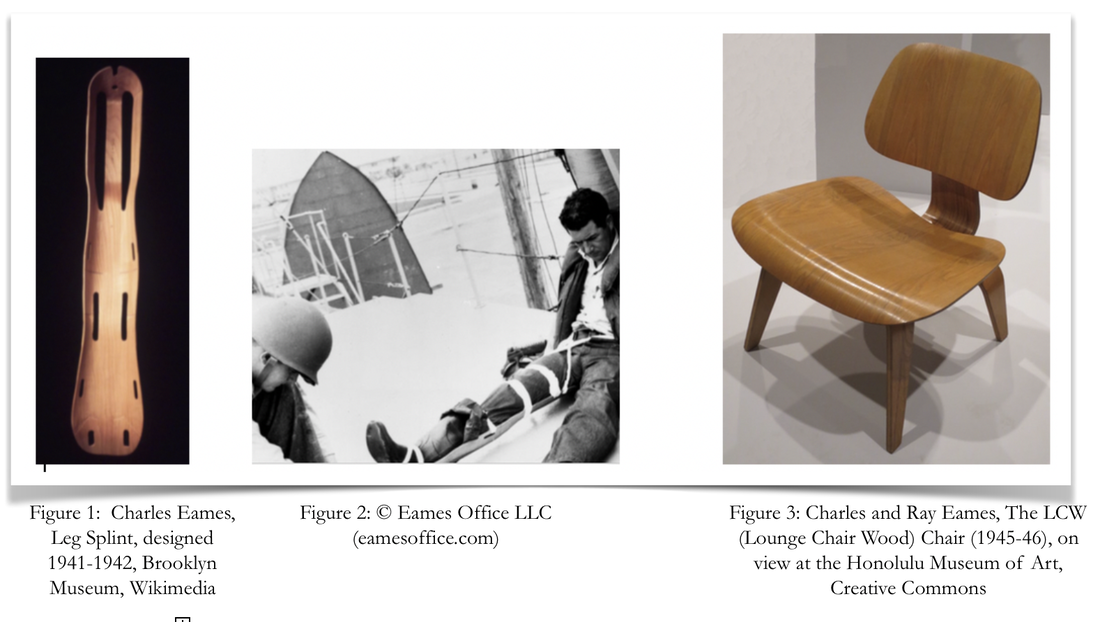

In the next class, I bring each student a pencil and sliver of found wood, and instruct them to hold and turn the fragment in their hands—feeling its striated textures and the bark’s knobs—before making a pencil rubbing in their writing journal. I remind them that wood, like marble and paper, invites subtraction. Another substrate with indwelling forms, wood suspends its carver’s intentions. As American artist David Esterly describes the living medium: a carver learns about wood (i.e. long-grain is strong, short-grain weak, and end-grain tough) “in his muscles and nerves. There is plenty of feedback from the wood.” Working in the high-relief and naturalistic style of the British wood carver, Grinling Gibbons (1648-1721), Easterly considers wood pliable, modeled by his intuitive hands.

In the next class, I bring each student a pencil and sliver of found wood, and instruct them to hold and turn the fragment in their hands—feeling its striated textures and the bark’s knobs—before making a pencil rubbing in their writing journal. I remind them that wood, like marble and paper, invites subtraction. Another substrate with indwelling forms, wood suspends its carver’s intentions. As American artist David Esterly describes the living medium: a carver learns about wood (i.e. long-grain is strong, short-grain weak, and end-grain tough) “in his muscles and nerves. There is plenty of feedback from the wood.” Working in the high-relief and naturalistic style of the British wood carver, Grinling Gibbons (1648-1721), Easterly considers wood pliable, modeled by his intuitive hands.

Woodcarving is hyperorganic, he says, the process a complex balance of a negotiated ecosystem of human and former tree. Unlike Michelangelo, whose figures struggle for liberation, carvers (like writers) labor with and against the wood (like words). As Esterly explains his athletic process: ambidextrous handling of chisels while anchoring the wood with his torso twisting in a contraposto way: “You take the resistance of the wood internally.” Once the general shape emerges, he undercuts the splintery form, defining the finer edges. Its contour deepens. Returning to their pencil rubbings at the class’s end, students prepare for their essays’ second-level revision, a kind of frottage of its story’s texture, its thick and subtle grains.

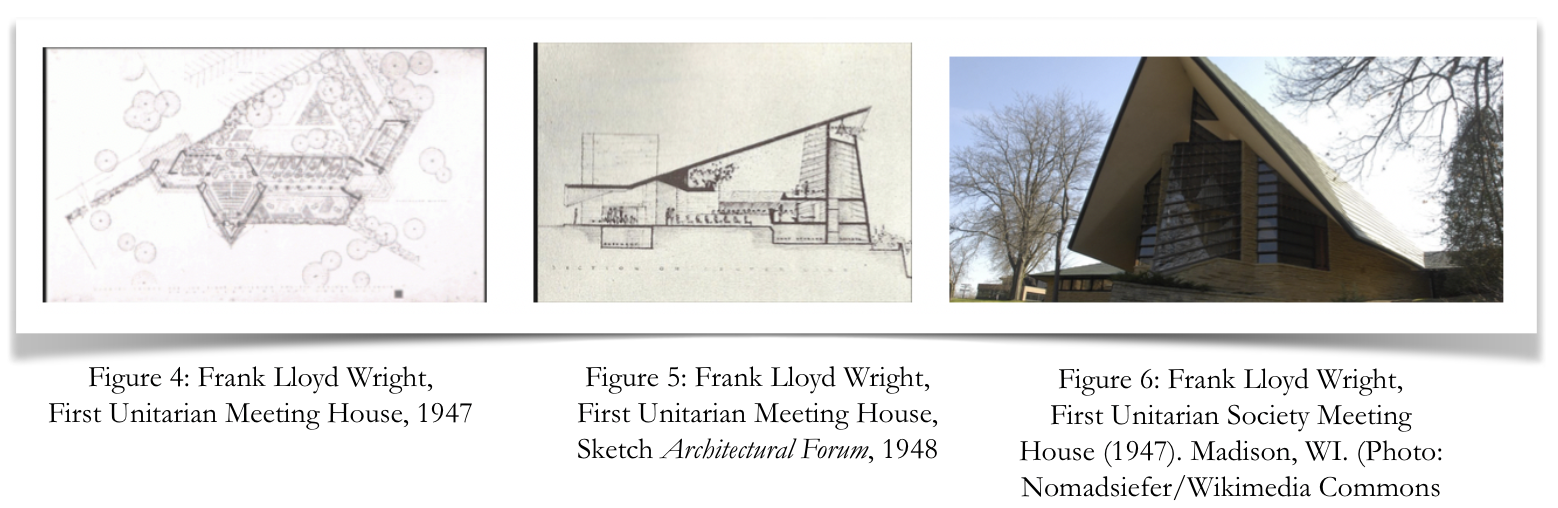

(Under)cuttings

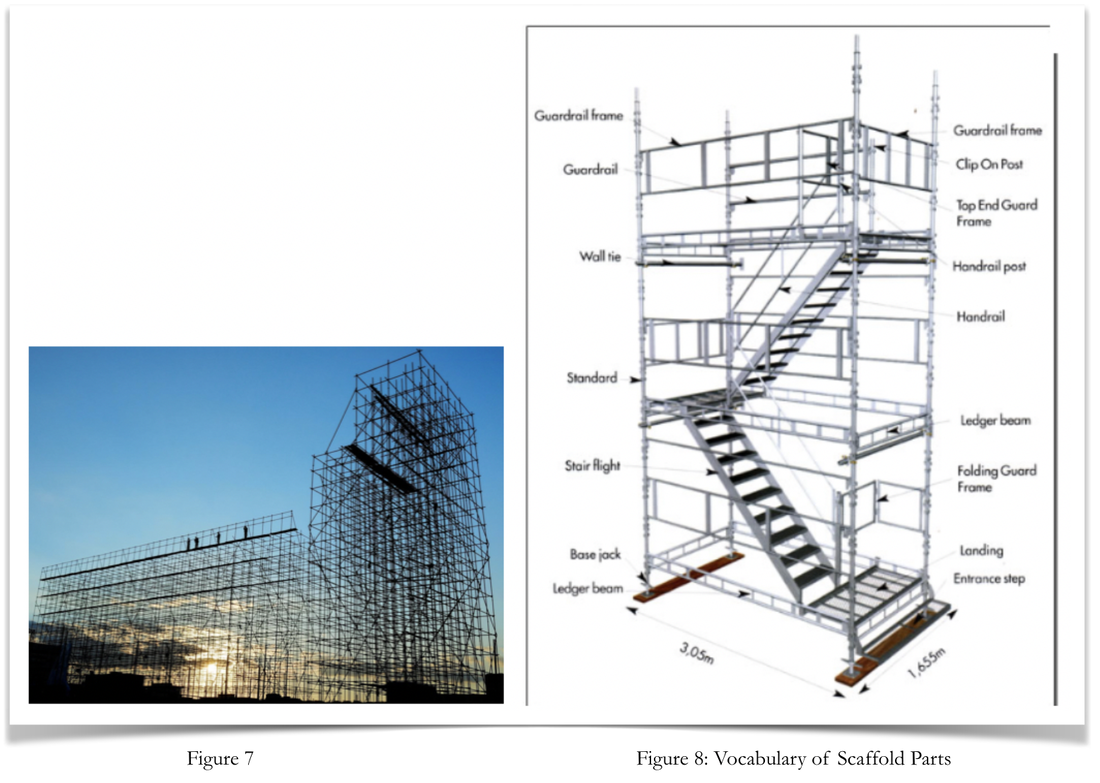

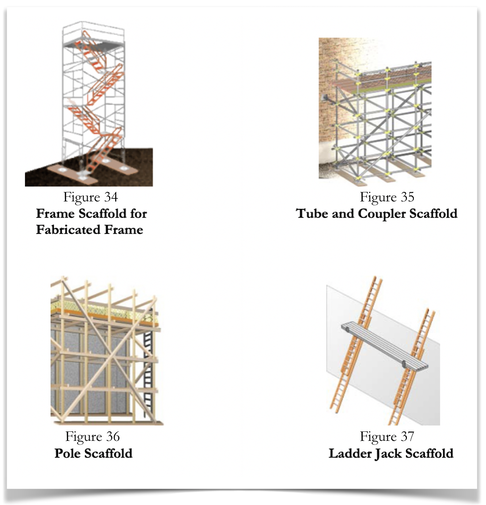

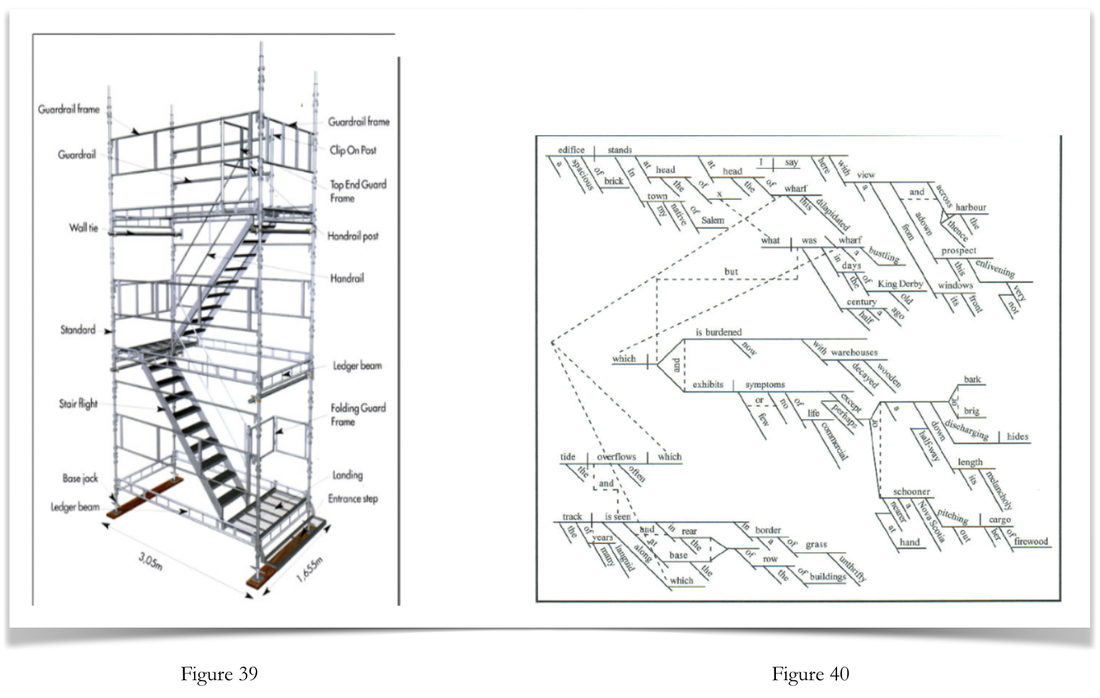

Because first-level revision’s subtractive methods have excavated the essay’s story and attendant architecture, the second-level process dismantles its suspended scaffold. Students proceed by cutting their essays into paragraph pieces, scattering them on a large seminar table or our classroom floor, having their peer groups reassemble them. Where description and exposition balance wobbles, where narrative gaps appear, where the transitions jar, they can see the essay scaffold’s weaknesses. Where its component parts and emerging story are unsupported. They accordingly reassemble the paragraphs from last to first (imitating a scaffold’s erection from bottom up) to test the revision’s integrity. Does the essay hold? Then they cut the unnecessary paragraphs, add transitions between the resulting fissures, and reconstruct the draft pieces one final time from the top down (imitating the scaffold’s final dismantling).

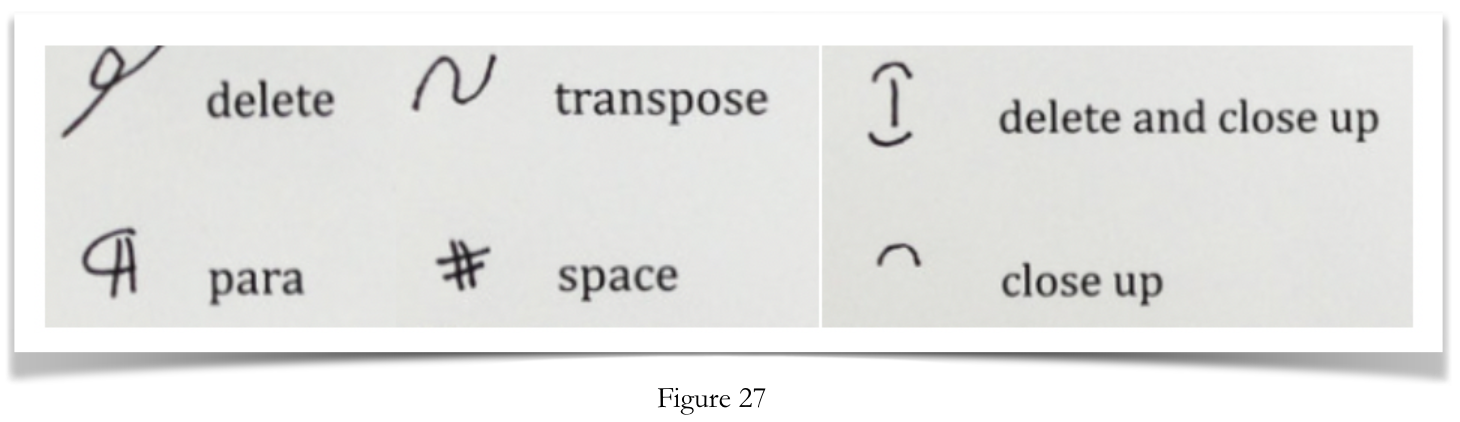

As subtractive artists, I point out, they have just successfully cut away the suspended scaffolds’ vertical standards and horizontal ledgers, the cross and façade braces that supported their draft’s labor. Bringing to class a clean copy of their typed drafts and a writing implement (the new bearers), they return to the remaining paragraphs, marking the places for sharp undercuttings of sentences: excessive verbiage, incorrect grammar, and awkward syntax are shaved away. Their editorial pentimenti--Cross-outs and arrows and ∧words—are a writer-construction worker’s most precise couplers, tightening the permanent construction so the scaffold can be fully removed:

As subtractive artists, I point out, they have just successfully cut away the suspended scaffolds’ vertical standards and horizontal ledgers, the cross and façade braces that supported their draft’s labor. Bringing to class a clean copy of their typed drafts and a writing implement (the new bearers), they return to the remaining paragraphs, marking the places for sharp undercuttings of sentences: excessive verbiage, incorrect grammar, and awkward syntax are shaved away. Their editorial pentimenti--Cross-outs and arrows and ∧words—are a writer-construction worker’s most precise couplers, tightening the permanent construction so the scaffold can be fully removed:

The editorial symbols (geometric in their own right) signal alterations for more efficient spatial configurations of a paragraph’s sentences. Every thought cleanly linked to the next. Every word carrying its own weight. After integrating these changes, students print and read aloud one more clean copy of the essay, asking themselves: What remains of the original object and what is now missing? How can I make each paragraph self-sustaining, while upholding the others?

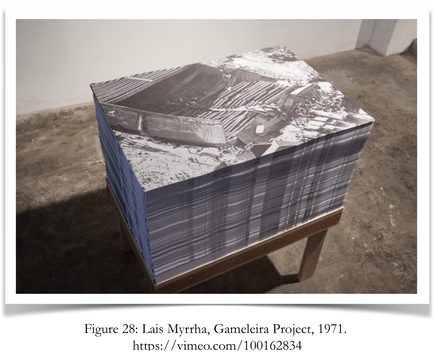

At this final stage of their second-level revision, we read a story about a doomed architectural marvel uncovered by Brazilian artist Lais Myrrha’s Gameleira Project. The situation: architect Oscar Niemeyer designed an exhibition park for the city of Belo Horizonte for the 1971 São Paulo Biennial. The story: part of the building slab collapsed, killing a hundred workers, but the military dictatorship covered it up for over forty years. Until Myrrha’s 2015 traveling exhibition.

At this final stage of their second-level revision, we read a story about a doomed architectural marvel uncovered by Brazilian artist Lais Myrrha’s Gameleira Project. The situation: architect Oscar Niemeyer designed an exhibition park for the city of Belo Horizonte for the 1971 São Paulo Biennial. The story: part of the building slab collapsed, killing a hundred workers, but the military dictatorship covered it up for over forty years. Until Myrrha’s 2015 traveling exhibition.

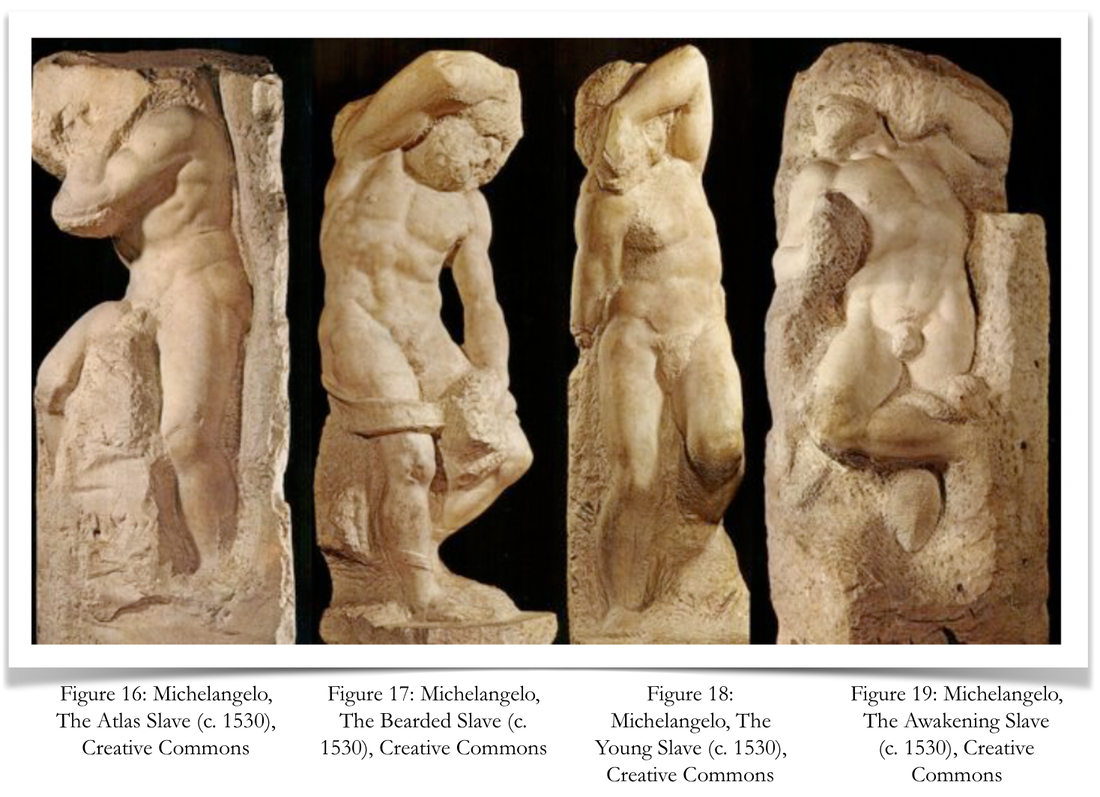

Through her archival reproduction and vertical exhibition of the singular extant photograph as an upright building’s paper architecture, Myrrha has brought the hidden story to the contemporary surface. She has unearthed the memory of forgotten manual laborers trapped beneath the failed scaffold’s rubble. Like Michelangelo’s Atlas slave, they have symbolically shouldered all of Brazil’s burdens under the dictatorship, emerging from the mass concrete-and-steel grave through a forbidden and hidden photograph. A non-finito project of trapped victims. A history of reversed cut-outs echoing Coron’s work, where the story never surfaces. An industrial undercutting revealing what lies beneath (so unlike Easterly’s hyperorganicism), carving texture into a misshapen cultural narrative.

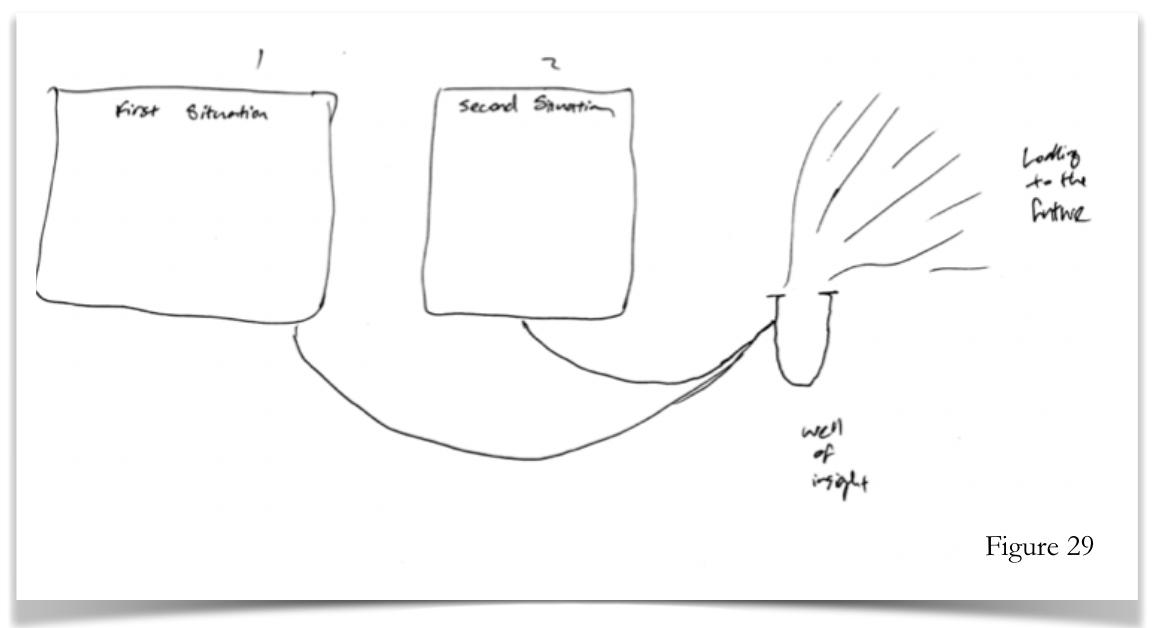

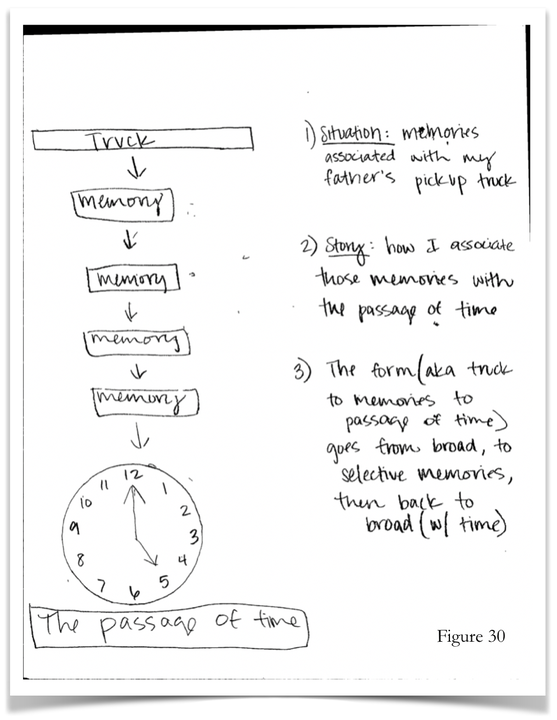

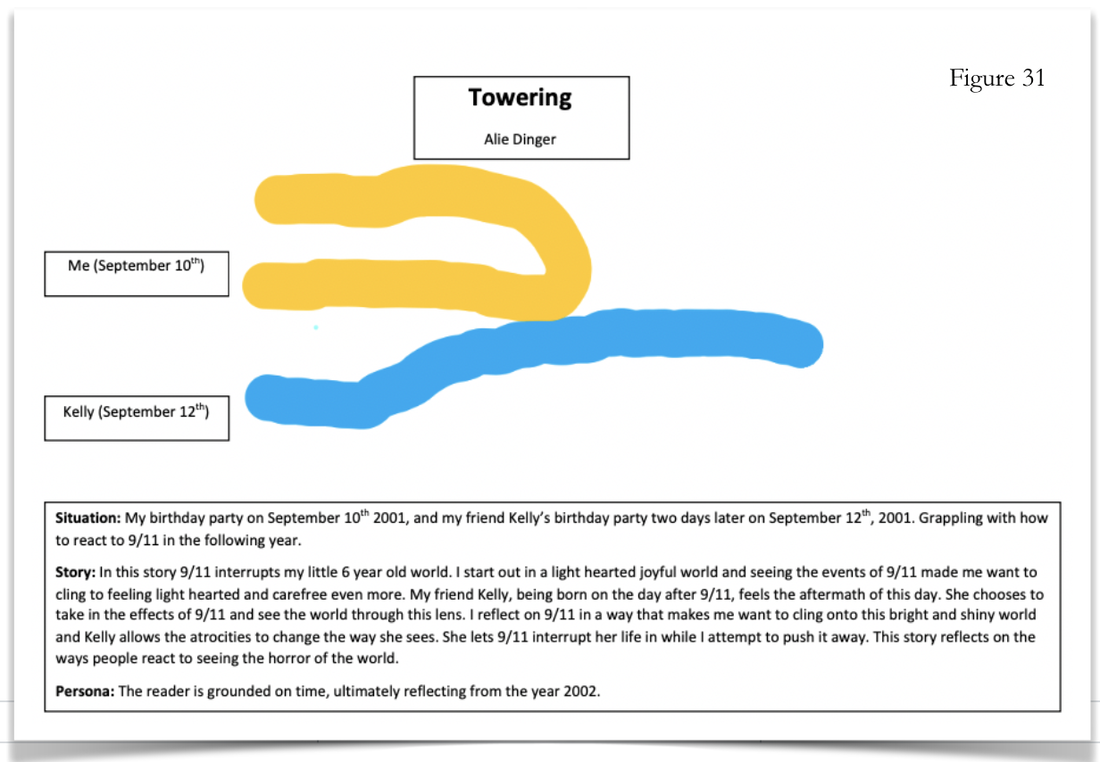

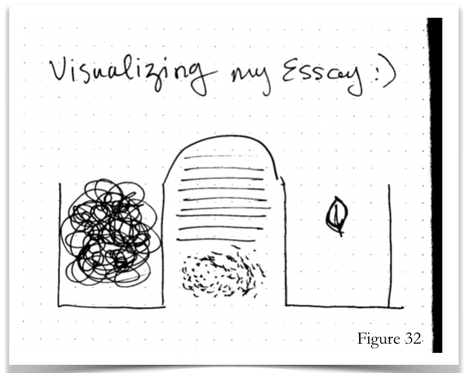

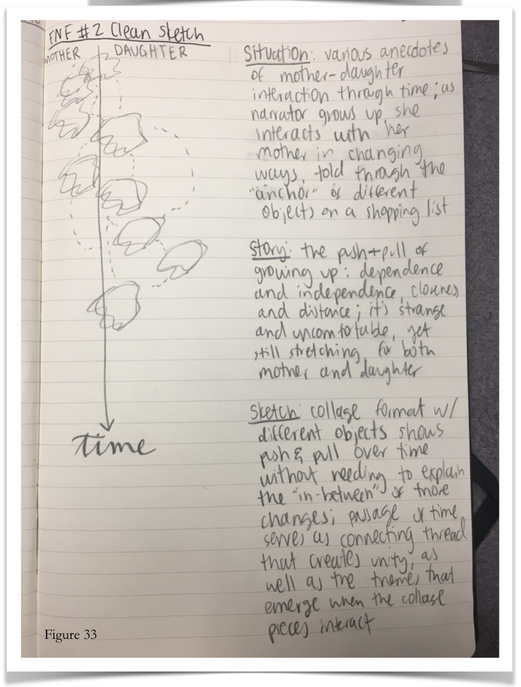

During her Texas tour, Lais left me several hundred prints of the accident site, which I distribute each semester to students as we discuss the cultural cover-up. The unarticulated lives buried beneath swept-away rubble. Think through analogy, I remind them. What is your revision still covering up or burying? Very likely part of the story you’ve been circling, overlooking, sensing, or avoiding. Turning to the print’s blank side, students do a new contour drawing of their revision’s altered architecture, which I post to our ecampus page. (They also copy it into their writing journal to archive the three-part revision exercise). Here are some examples (Figures 29-33):

During her Texas tour, Lais left me several hundred prints of the accident site, which I distribute each semester to students as we discuss the cultural cover-up. The unarticulated lives buried beneath swept-away rubble. Think through analogy, I remind them. What is your revision still covering up or burying? Very likely part of the story you’ve been circling, overlooking, sensing, or avoiding. Turning to the print’s blank side, students do a new contour drawing of their revision’s altered architecture, which I post to our ecampus page. (They also copy it into their writing journal to archive the three-part revision exercise). Here are some examples (Figures 29-33):

With the exception of one student (who transcribed her sketch into typescript), the hand-drawn and annotated blueprints are noticeably architectural (though I gave no leading instructions): squares and rectangles in horizontal and vertical matrices, full and broken lines, and directive arrows guiding the construction’s progressive, recursive, and digressive movements. This tactile exercise handles the draft once again as a physical object. And their sketches, a kind of automatic, instinctive, and organic rendering, routinely portray the essays as living, evolving things.

Supported Scaffolds: Tinker Toys, Bricolage, and Sentence Diagrams

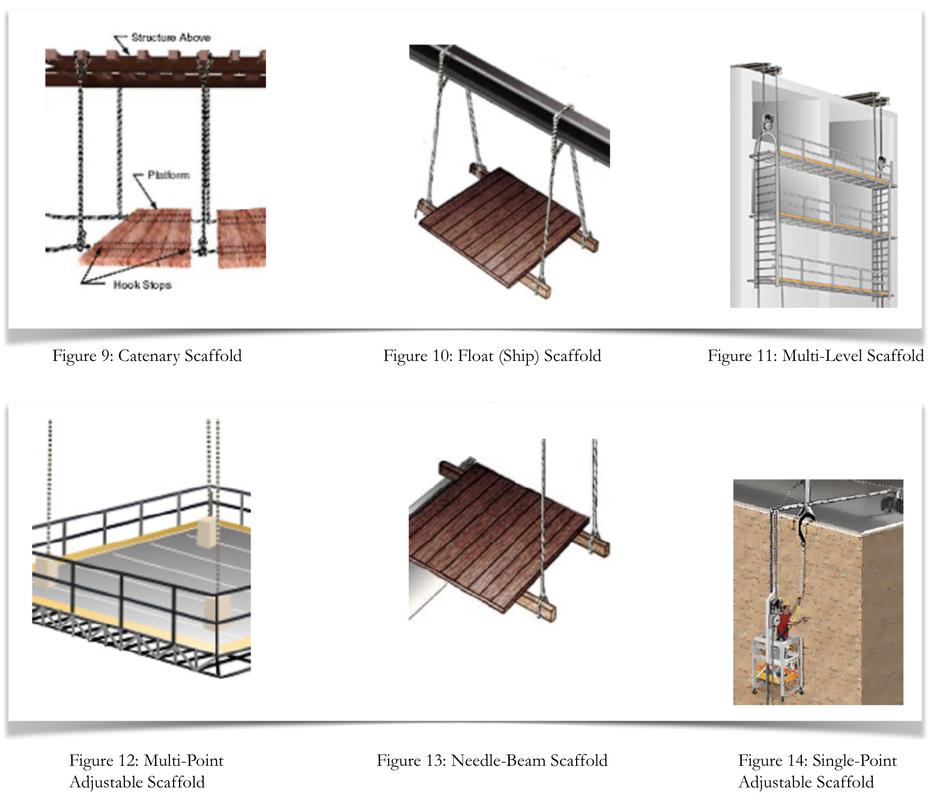

The third-level and final revision focuses on crafting artful sentences, picking up on their initial editorial undercuttings. Sentences, students quickly discover, are an essay’s supportive scaffold, its fundamental architecture, its ultimate bearer. Each one a platform supported by rigid beams and poles and legs and posts. Each one a brilliant assembly of parts of speech, grammar, and syntax. Artfully crafted, they balance the entire essay while allowing it momentum and pause, curve and bend.

After a brief discussion of the supported scaffolds above (emphasizing permanence and stability over freeplay and suspension), I ask what they know (and how they learned) about sentence structures. I tell them that they have to forgo their suspended scaffolds for more stable frames.

Volunteers list their collective knowledge on the white board as a working reference guide, while I spill a huge tub of brightly colored Tinker Toys on the classroom floor within our circle of desks: the spools, wheels, sticks, cylindrical caps, couplings, and pulleys fill the open space. The vocabulary of a familiar childhood toy is a sentence scaffold’s vernacular. Nouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives, pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions and interjections configured into subjects and predicates, objects and complements, phrases and clauses. Students play with the toy pieces, feeling the wood’s pre-cut grooves and holes, its minute textures. I interrupt with a simple writing prompt: Assign a part of speech to each of these Tinker Toy pieces. How do the language elements and their functions relate to the associated wooden parts as you see them?

Subjects and predicates are the anchoring spool. Their modifiers are the fastened sticks, phrases and clauses their pulleys, objects and complements their couplers. More than a children’s game, tinkering encourages a playful approach to sentence design and revision. Puttering, fiddling, experimenting, and adapting in the course of making repairs or improvements, tinkering is thinking-through-doing. As tinkerers, writers manipulate rather than re-memorize (what to 21st-century students seems stultifying) grammar and syntax conventions; instead we put them into play, purposefully and inventively. As sentence-makers, we are engaged bricoleurs, our hands and mind taking up the known world—what is right in front of us—and seeing it as if for the first time, giving it meaningful form (Dezeuze).

I show two quick videos: Gever Tully’s Ted Talk, “Life Lessons Through Tinkering” and Edith Ackermann, “Pedagogical Perspective on Tinkering and Making,” followed by a slide show of contemporary bricolage art. The final slide shows mixed media artist Pamela Winegard’s provocative and untitled bricolage (see Figure 38), which prompts our class discussion. Students name the recognizable objects (and their original form and function): black elastics and hair scrunchies, copper wire, sticks, part of a wooden placemat, encaustic paint, and Winegard’s penciled pentimenti on the paper’s underlayer. They note how commonplace the objects are, how familiar their materials. Things that they take for granted or overlook in daily life. Put into new contexts in unexpected juxtapositions, each part not only becomes more evident but also a vital part of the whole. (For a rich demonstration, see Arlene Schechet, “Pentimento in Paper.”)

Volunteers list their collective knowledge on the white board as a working reference guide, while I spill a huge tub of brightly colored Tinker Toys on the classroom floor within our circle of desks: the spools, wheels, sticks, cylindrical caps, couplings, and pulleys fill the open space. The vocabulary of a familiar childhood toy is a sentence scaffold’s vernacular. Nouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives, pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions and interjections configured into subjects and predicates, objects and complements, phrases and clauses. Students play with the toy pieces, feeling the wood’s pre-cut grooves and holes, its minute textures. I interrupt with a simple writing prompt: Assign a part of speech to each of these Tinker Toy pieces. How do the language elements and their functions relate to the associated wooden parts as you see them?

Subjects and predicates are the anchoring spool. Their modifiers are the fastened sticks, phrases and clauses their pulleys, objects and complements their couplers. More than a children’s game, tinkering encourages a playful approach to sentence design and revision. Puttering, fiddling, experimenting, and adapting in the course of making repairs or improvements, tinkering is thinking-through-doing. As tinkerers, writers manipulate rather than re-memorize (what to 21st-century students seems stultifying) grammar and syntax conventions; instead we put them into play, purposefully and inventively. As sentence-makers, we are engaged bricoleurs, our hands and mind taking up the known world—what is right in front of us—and seeing it as if for the first time, giving it meaningful form (Dezeuze).

I show two quick videos: Gever Tully’s Ted Talk, “Life Lessons Through Tinkering” and Edith Ackermann, “Pedagogical Perspective on Tinkering and Making,” followed by a slide show of contemporary bricolage art. The final slide shows mixed media artist Pamela Winegard’s provocative and untitled bricolage (see Figure 38), which prompts our class discussion. Students name the recognizable objects (and their original form and function): black elastics and hair scrunchies, copper wire, sticks, part of a wooden placemat, encaustic paint, and Winegard’s penciled pentimenti on the paper’s underlayer. They note how commonplace the objects are, how familiar their materials. Things that they take for granted or overlook in daily life. Put into new contexts in unexpected juxtapositions, each part not only becomes more evident but also a vital part of the whole. (For a rich demonstration, see Arlene Schechet, “Pentimento in Paper.”)

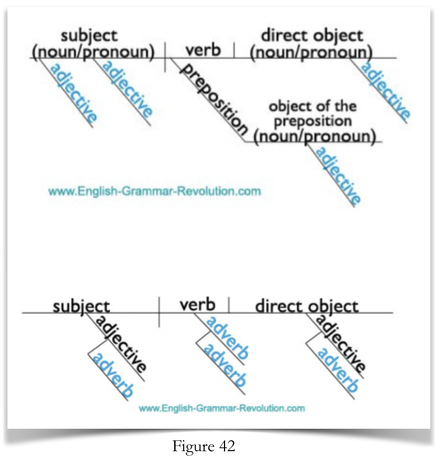

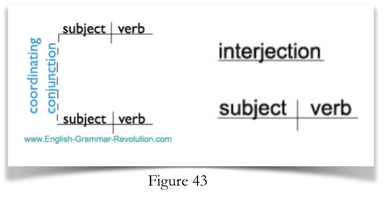

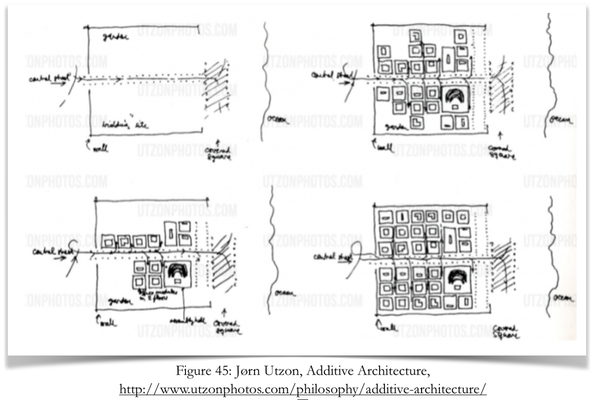

An Additive Art (complementing the subtractive arts of first- and second-level revision), [6] brioclage is an appealing segue to sentence diagramming. To introduce sentence architecture as an art that manipulates the known elements of speech, transforming the age-old parts into an exciting whole. Rather than removing excess, sentence diagrams builds a complex, layered, and seemingly three-dimensional structure. Each separate and moveable part with indwelling potential for countless permutations and combinations. As Gertrude Stein famously mused: “I really do not know that anything has ever been more exciting than diagramming sentences. . . . the one thing that has been completing exciting and completely completing. . . . I like the feeling the everlasting feeling of sentences as they diagram themselves.” A “sentence should force itself upon you, make you know yourself knowing it” (Stein 290). An essayist’s job is to know themselves.

My job is to prove Stein right.

Think about each sentence in your essay as a bricolage of familiar and well-used objects, hand-arranged to express your ideas. Look where the parts merge, where they overlap in unusual layers. They are supportive scaffolds, quiet bearers of the cumulative story.

My job is to prove Stein right.

Think about each sentence in your essay as a bricolage of familiar and well-used objects, hand-arranged to express your ideas. Look where the parts merge, where they overlap in unusual layers. They are supportive scaffolds, quiet bearers of the cumulative story.

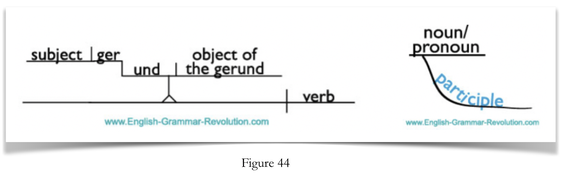

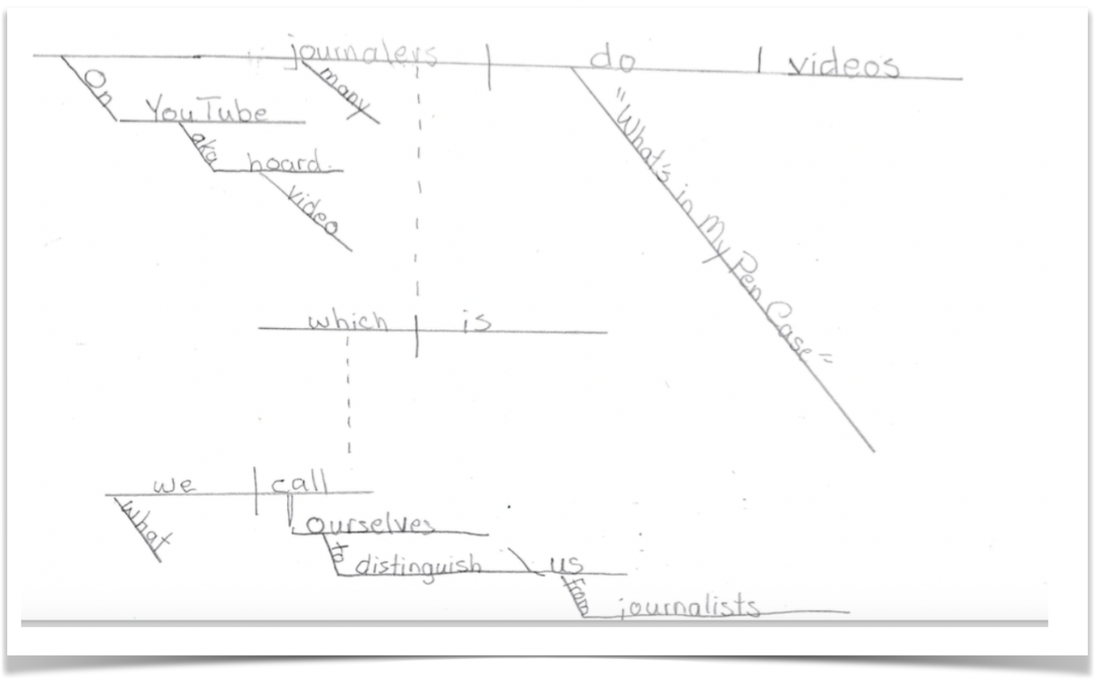

Study the building and sentence scaffolds side-by-side. See how the subject and predicate form the base jack, the standard bearer on which everything relies. How the vertical standard slices the noun and action verb, while angling the linking verb along a reclining diagonal.

Notice, too, how indirect objects, objects of a preposition, adjectives, adverbs, connect like folding guard frames beneath the words they modify.

Consider how these modifiers’ vertical, horizontal, and diagonal elements are held in perfect balance. And what of the conjunction’s graceful coupling: a hyphenated handrail holding parallel levels in cantilevered permanence? And an interjection floating like a ship above the sentence’s action.

And here is the gerund, happening as we watch, held in motion by a ladder-jack design. See the verb climb, the ing on the entrance step below, connected to the rest of the diagram with the forked line of a leveling jack.

The fork swings and we ride a participle’s down-turned wave, curving beneath and scooping up the subject it modifies. Formed by a verb, it acts as an adjective. A carnivelesque marvel. And all with the balance, proportion, and harmony of classical architecture.

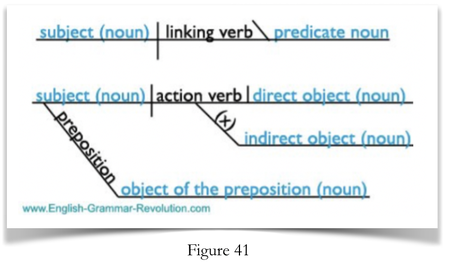

After my enthusiastic pitch and before they try their hand at diagramming the sentences from one of their revision’s paragraphs, we do close analyses of the increasingly complex examples in Kitty Burns Florey’s fabulous book, Sister Bernadette’s Barking Dog: The Quirky History and Lost Art of Diagramming Sentences.

Posting their own sentence diagrams to our ecampus page, students exchange and discuss them in peer groups and then volunteer to present to the full class:

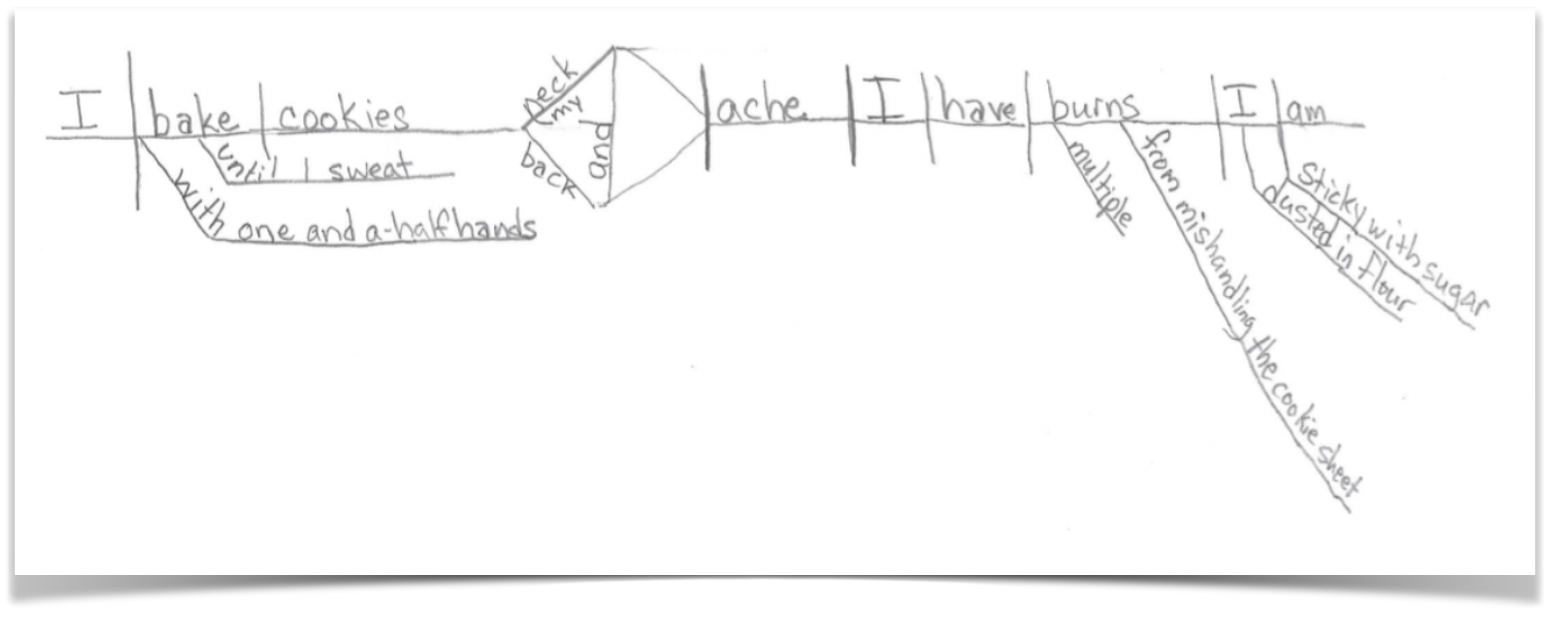

Example 1: I bake cookies with one-and-one-half hands until I sweat, my neck and back ache, I have multiple burns from mishandling the cookie sheet, and I am dusted with flour, sticky with sugar.

After my enthusiastic pitch and before they try their hand at diagramming the sentences from one of their revision’s paragraphs, we do close analyses of the increasingly complex examples in Kitty Burns Florey’s fabulous book, Sister Bernadette’s Barking Dog: The Quirky History and Lost Art of Diagramming Sentences.

Posting their own sentence diagrams to our ecampus page, students exchange and discuss them in peer groups and then volunteer to present to the full class:

Example 1: I bake cookies with one-and-one-half hands until I sweat, my neck and back ache, I have multiple burns from mishandling the cookie sheet, and I am dusted with flour, sticky with sugar.

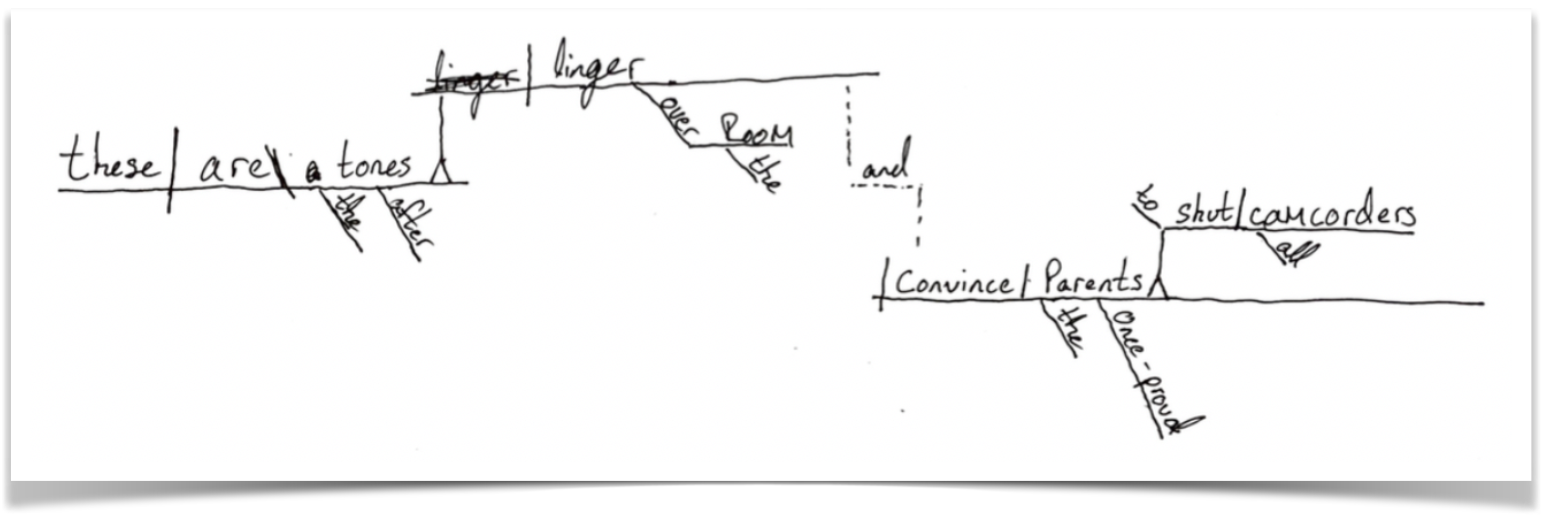

Example 2: These are the after tones that linger over the room and convince the once-proud parents to shut all camcorders (only after deleting the evidence).

Example 3: On YouTube, aka video hoard, many journalers—which is what we call ourselves to distinguish us from journalists—do “What’s in My Pen Case” videos.

As students draw and explain their sentence’s architectures, they begin to understand the parts of speech and syntax as physical, supportive structures. As tangible, moveable, and interlocking parts suspended between the material world and our articulation of it. They see (even with the minor diagramming errors) where their sentences are strong and where they totter. They see that three unnecessary prepositional phrases weigh down a single sentence; they see the excessive adverbs and adjectives belaboring the obvious; they see subject and verb disagreement; they see sentence fragments and run-ons; even a dangling modifier. In other words, they see what my repeated Simplify Prose comments in their papers mean. A scaffold’s weakest joint is a correctable mistake. It is the space where a writer-construction worker applies the finishing touches from top to bottom, from inside out. We step down, our job complete. And the structure stands on its own.

Conclusion: On Manual Labor and the Pleasures of the Imagination

Contour drawings, silhouette cuts, frottage, tinkered scaffolds, and sentence diagramming are all haptic exercises in revision. They teach creative nonfiction students that language is active and adaptable raw material in our hands. Because writing is a complex mode of embodied cognition relying on intricate perceptual-sensorimotor combinations (Noë, O’Reagan). It is neither muse-inspired or mystical, but rather requires our mental and manual labor. An essayist’s stories evolve from their perception and lived experience of the world, and that perception, neuroscientists have proved, is more than visual. It is a nuanced interaction of touch: exploratory hand movements, object manipulation, and brain function. In other words, our hands’ movements and performances relate to what goes on in our brains. Until recently, the perceptual capacities of hands have been ignored by an emphasis on their motor capacities: “we grasp, push, pull, lift, carry, insert, or assemble” for practical purposes (Gibson 123). Yet writing by hand (rather than solely composing on a computer) helps train our brains to integrate thinking with fine motor dexterity (Mangen and Velay). Regardless of one’s writing process, revising by hand brings the story into relief. Our haptic engagement with words—both proprioceptive and kinesthetic--emphasizes that our texts are autonomous objects. Drawing and tracing, cutting and pasting, penciling editorial marks, and diagramming sentences, we disassemble and reassemble our essay’s constituent parts by hand. We reorient ourselves to the work and make the familiar strange. And wonderful. Live by analogy, I tell my creative nonfiction students.

Notes

|

[1] On analogical design, see Andrea Ponsi, Architecture and Design (University of Virginia Press, 2015) and M. Gross and E. Do, “Drawing Analogies—Supporting Creative Architectural Design with Visual References.” 3rd International Conference on Computational Models of Creative Design, eds. M-L Maher and J. Gero (Sydney: University of Sydney, 1995): 37-58.

[2] Poet Diane Ackerman encourages a similar form of experiment in Deep Play, Vintage, 2000. [3] Other useful approaches to finding an essay’s “design” include anything written by Ander Monson. For example, “Essay as Hack,” The Far Edges of the Fourth Genre: An Anthology of Explorations in Creative Nonfiction. Ed. Sean Prentiss and Joe Wilkins (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2014): 9-22. See http://otherelectricities.com/ for links to his other work and projects. [4] A rich analogy to a writer’s compositional process, pentimento in painting and sculpture is a kind of underwriting: a still-visible layer of an earlier iteration of the evolving artwork (i.e. a shadow, line, color, chisel mark, etc.) [5] The two historical traditions in hand-cut silhouettes manipulate positive and negative space. "Cut-out silhouettes" are images cut from a dark material (usually black paper) and mounted onto a heavy cream-colored card. "Hollow-cut silhouettes" are figures cut from a piece of light-colored paper, leaving the negative space outside of the image, which is then backed with dark paper or fabric. [6] On the design evolution of Additive Architecture, see Kenneth Frampton, “The Architecture of Jørn Utzon” (The Pritzker Architecture Prize, Prize Hyatt Foundation, 2003). |

|

Susan M. Stabile is an Associate Professor of English at Texas A&M University, where she teaches courses in Creative Nonfiction, Material Culture and Museum Studies, Literature and the Other Arts, and Narrative Medicine. Her academic publications include Memory’s Daughters: The Material Culture of Remembrance in Eighteenth-Century America (Cornell University Press, 2004). Stabile’s creative work has appeared in The Iowa Review, The Bellingham Review, and The Southwest Review. She won the 2017 Annie Dillard Award in Creative Nonfiction at The Bellingham Review and had another essay nominated as a “Notable Essay of 2014” by The Best American Essays series. Stabile is the recipient of notable awards and honors, including a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship, Andrew Mellon Foundation grant, Winterthur Museum fellowships, and several writing residencies at Ragdale, Vermont Studio Center, and Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She is currently completing her first collection of creative nonfiction essays, Salvage, an unconventional reflection on contemporary recycling practices (from organ transplants and roadkill to birds’ nests and dopamine scaffolds) through what she calls a poetics of redemption that reclaims our waste and our intimate connections to it.

|