ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

5.2

5.2

|

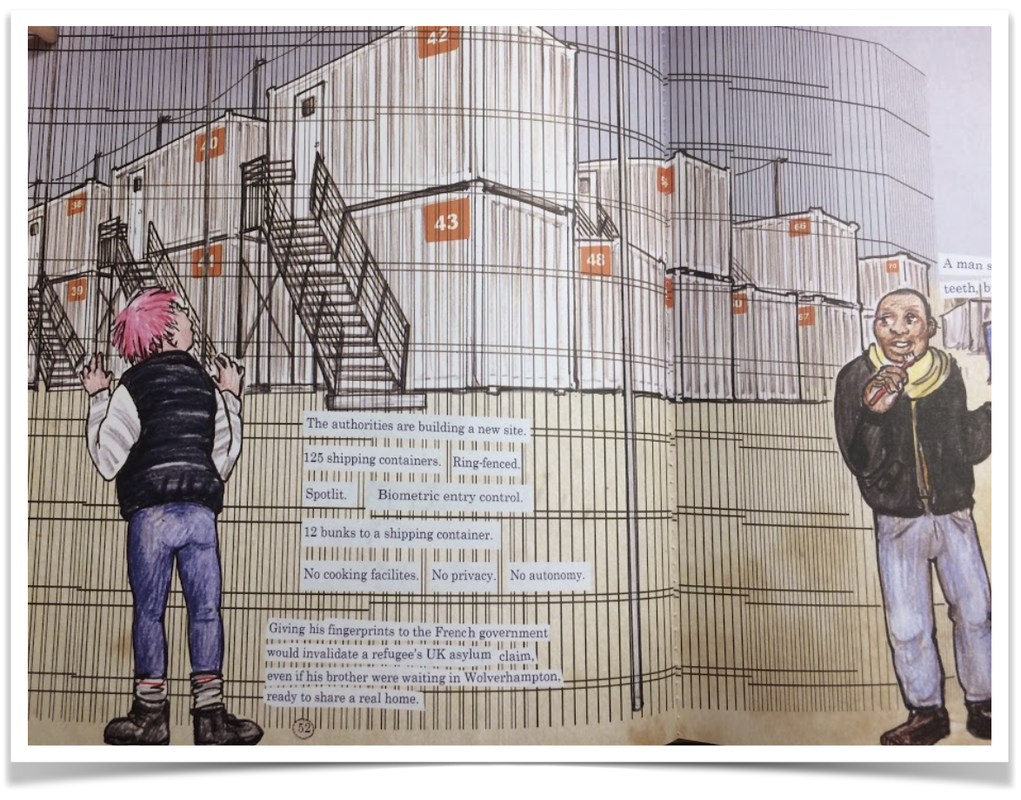

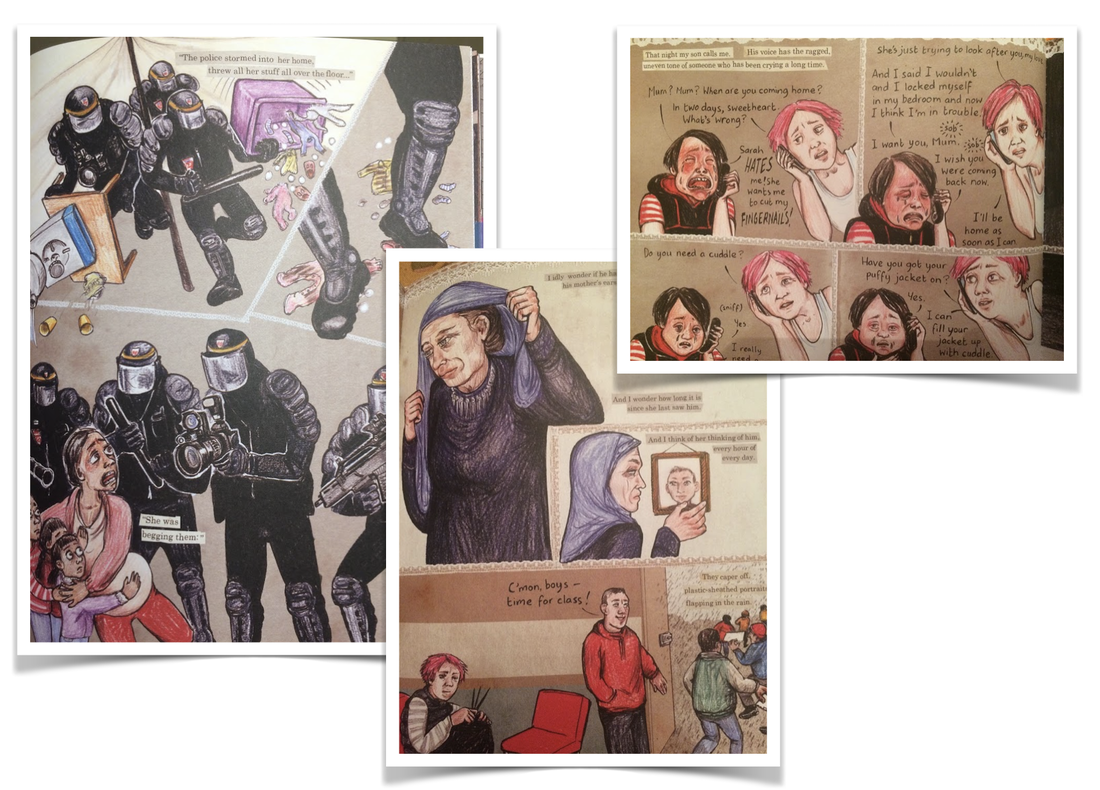

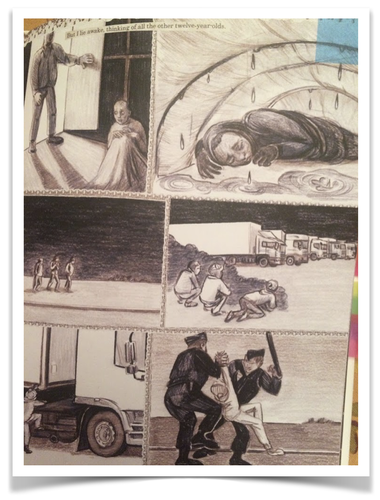

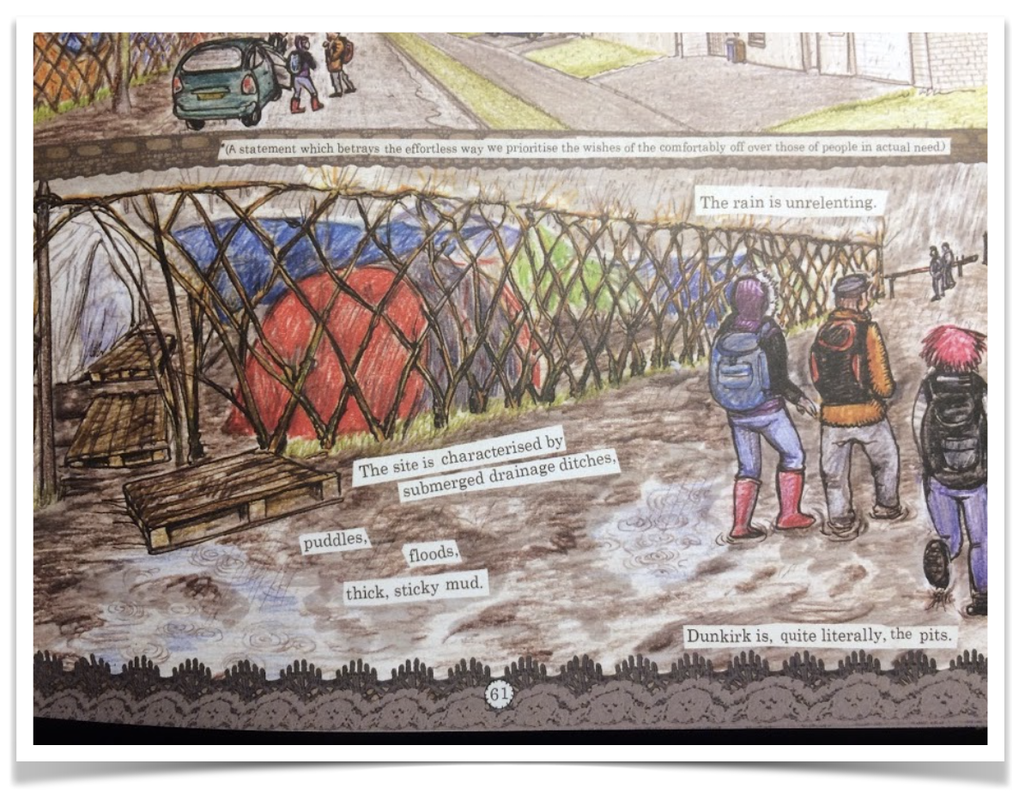

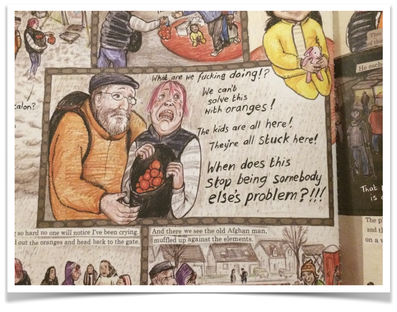

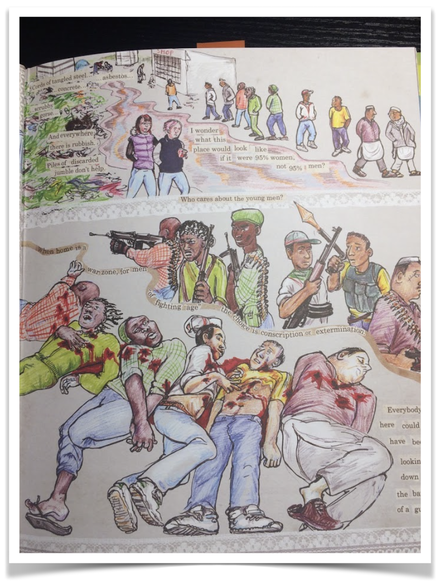

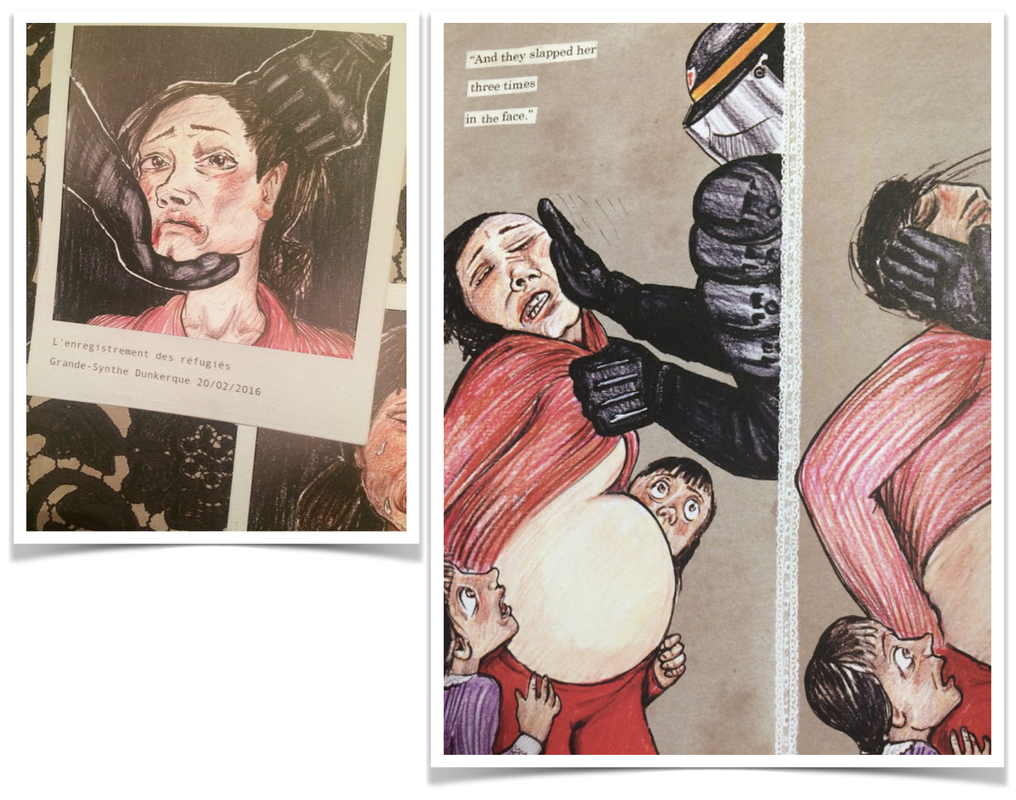

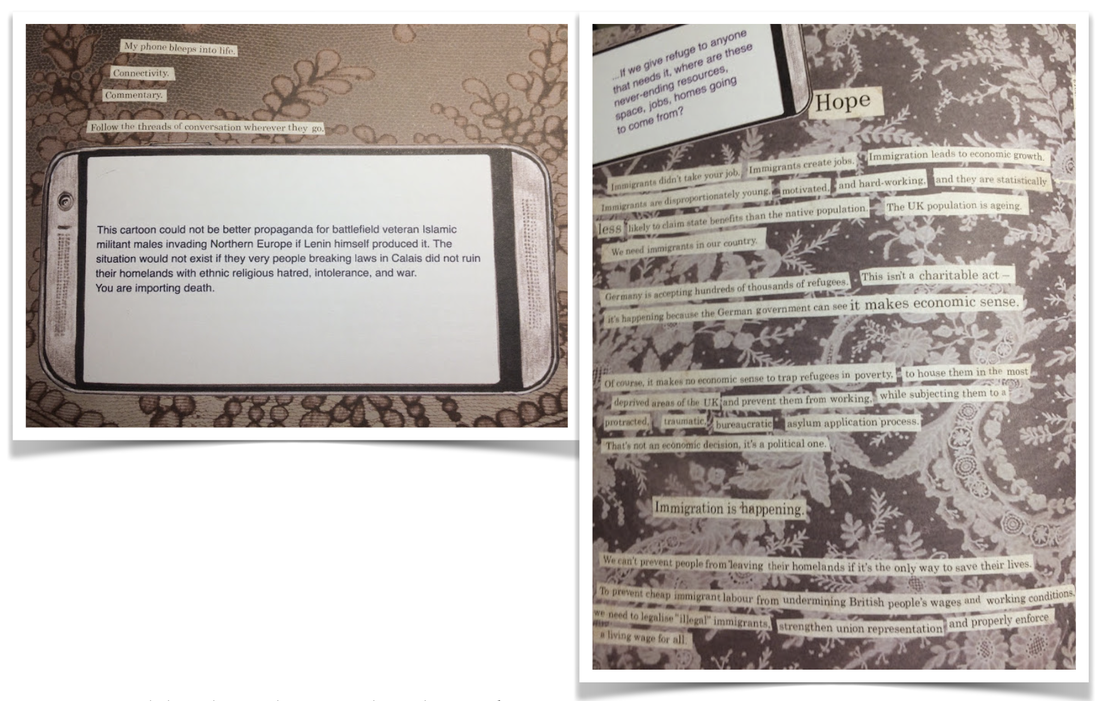

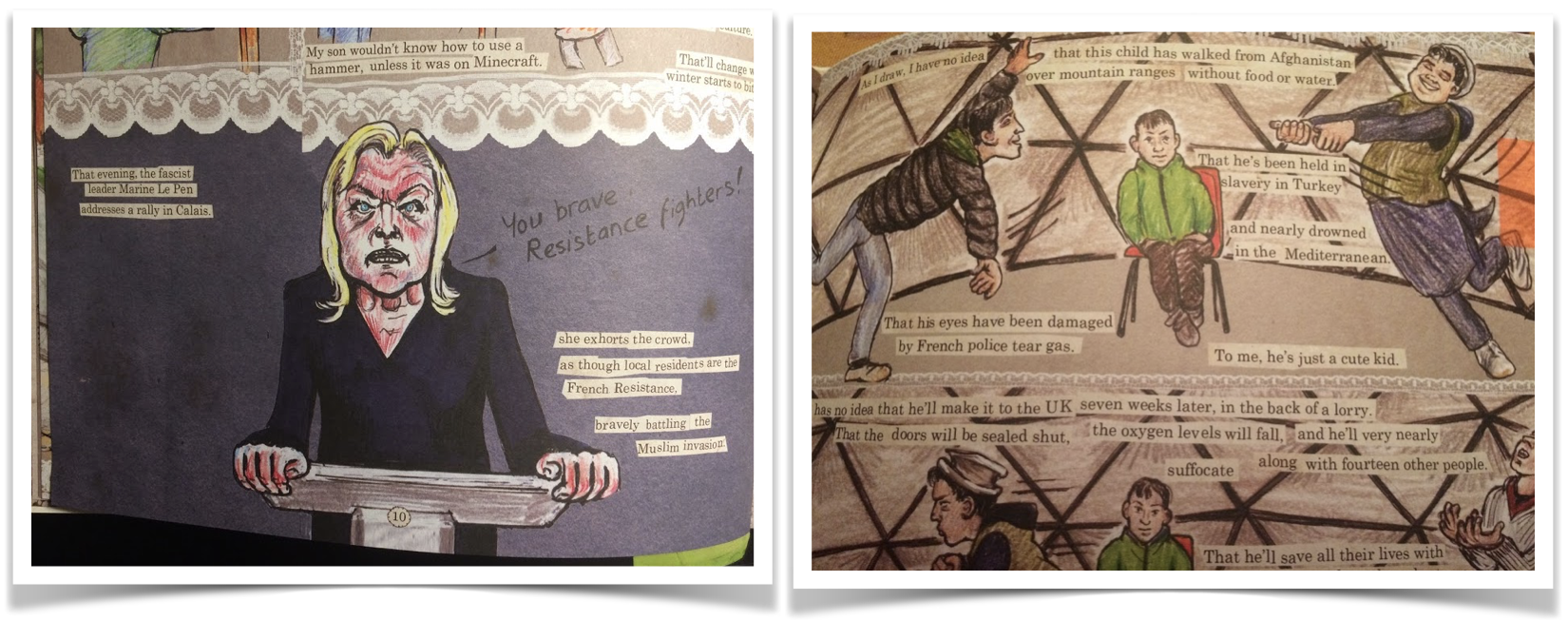

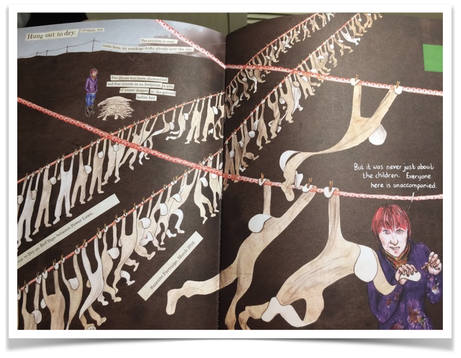

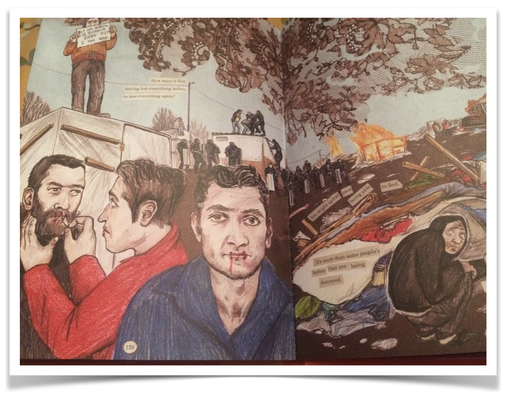

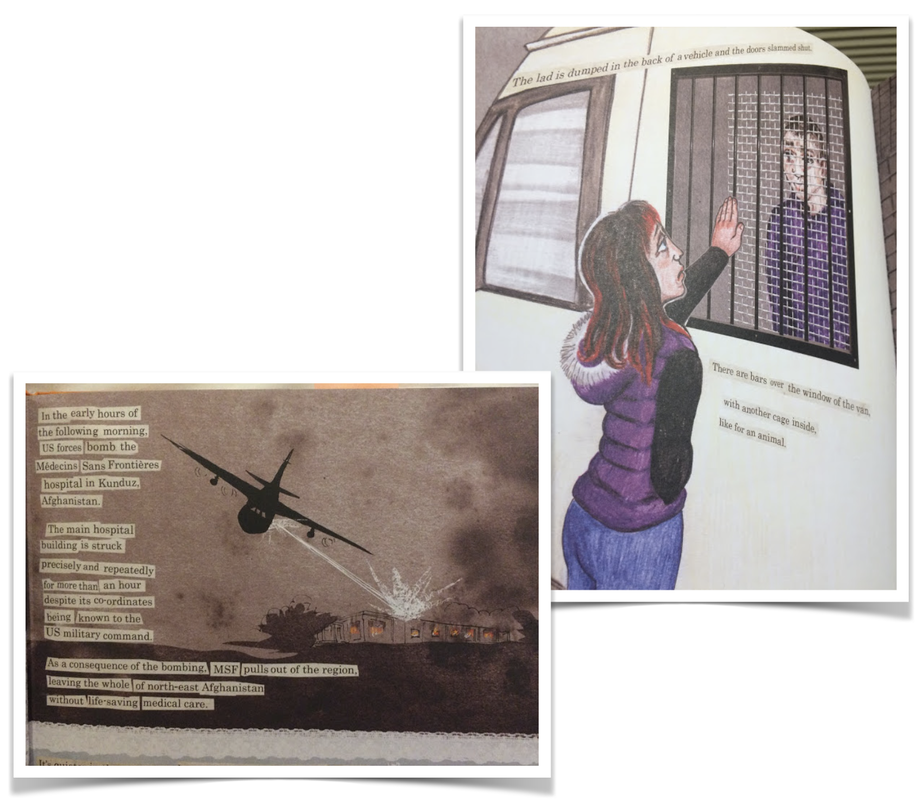

Threads: From the Refugee Crisis, a graphic reportage by British cartoonist, nonfiction writer, and activist Kate Evans, documents the abysmal living conditions and inhuman treatment of the refugee population in a camp in Calais, France, also known as the “jungle,” at the hands of French riot police and British anti-immigration officers. By the time Threads was published in 2017, the “jungle” had already been dismantled, but with a history of 10,000 asylum seekers, forced to languish for months and years, much like the detention center in Woomera, Australia, it has become a symbol of Europe’s anti-humanitarian policy and refusal of basic human rights to one of the most vulnerable populations (Buken 80). As a representational technique, Evans draws sketches of the wrenching reality of this intractable problem, as she witnessed it herself, to narrate how Europe’s sovereign states dehumanize human subjects and punish those who are already fleeing war and political unrest in their home countries. Evans’ skillful drawing speaks of literary and artistic excellence where traditional forms of reading and learning are blurred, and a piece of nonfiction is transformed to serve as an historical archive. Threads also has an underlying metanarrative about the non-refugee volunteers who work in the refugee camp, but find themselves equally disadvantaged when they dare to challenge government policies.

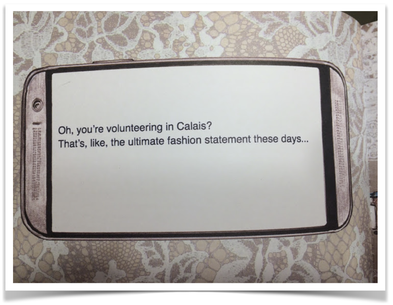

The sketches in the book describe the ten days that Evans spent as a volunteer in the camp, where she documents the appalling living conditions of the asylum seekers as a witness, but what makes her narrative fascinating is her conscious effort to not speak for the migrants but to speak with them as she details their harrowing experiences. In her endorsement of the book, Alison Bechdel writes how Evans’ aligns art with reality by transforming “the human ‘flood’ into shimmering droplets as she works and eats with the refugees, getting to know them as individuals, forging intimate connections while sketching their portraits.” In other words, Evan’s representation does not engage in a coercive rearrangement of the other’s desire, but instead forms an equal relationship with the subjects of representation. To do so, Evans rhetorically represents the asylum seekers as agents of history and not passive victims, and she uses different visual techniques, like the use of neutral skin color for all the characters in order to avoid stereotypical identity politics, similar facial reaction to violence. The use of humor to address xenophobia is particularly effective because it puts a human face to the “refugee crisis” and advocates for the right to live with dignity. To fully understand the socio-political and economic ramification of the government’s anti-immigration policy, Evans simultaneously compares her own experience as a “free” citizen with that of the dwellers of the camp, and criticizes policies that exploit human lives for biopolitical warfare. She puts forward the same question that Hannah Arendt asked long ago about the notion of human rights, which is based on the existence of a “human being as such,” a question put to crisis whenever Europe is faced with refugees (Arendt 299). The realistic sketches capture the ugly side of humanitarianism that force asylum seekers in “non-places” like the refugee camps and detention centers, leading them to dwell in a permanent state of exception. Moreover, it excludes the migrants from any legal protection while compelling them to abide by the law, creating a subaltern condition of living with no human right (Buken 70).

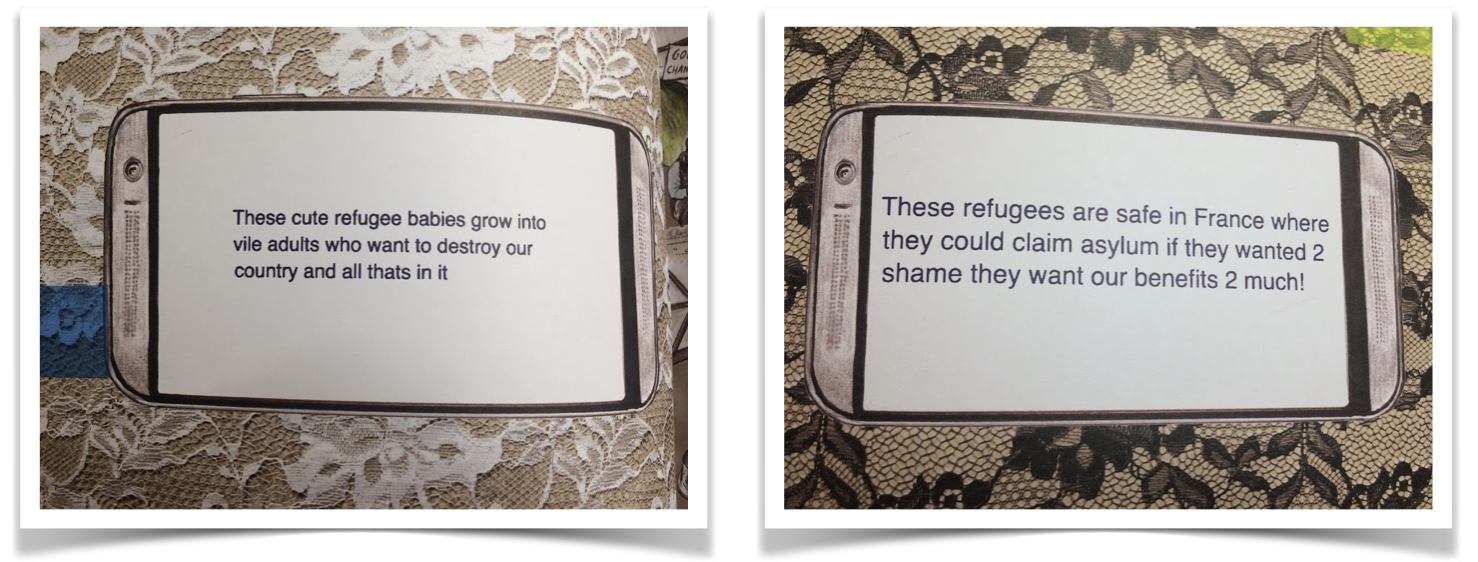

By addressing issues that are either silenced or misrepresented in the mainstream, Threads, quite literally, draws “history from below”and makes marginal voices visible in places where it has been stopped from historicization, and presents the refugee as a human who is affected by war, food insecurity, lack of political representation, but is a conscious subject who has a right to history of their own. Evans, with her sketches, counters the image of the “refugee” that is variously constituted to mean either objects of pity or subjects of threat to the western civilization, “signifying the [...] impossibility of occupying one pure and distinct position” (Buken 79). By literally creating a different image in order to deconstruct the established image of asylum seekers, Evans questions the method of “objective” journalism and social media campaigns in the era of heightened communication and technological advancements that makes it difficult to consider the refugee as an eligible candidate for asylum. By showing the refugee population in a positive way, the negative stereotype of the refugee as an abuser of the welfare system is destabilized (Buken 79). Therefore, Evans’ pictorial narrative acts as an effective and affective counter narrative to the daily reproduction of false history and negative stereotype about the refugee population in the media and elsewhere for consumption of the common people, profit of multinational corporations, resulting in the mass reproduction of xenophobia, racism, and sexism.

Threads, then, is a kind of book that, to use Rob Nixon’s definition, “expose silences that can be dismantled through…rhetorical creativity, and by advancing counter histories in the face of formidable odds” (Nixon “Slow Violence”). With this perspective in place, this article critically examines this text as a non-fiction important for literary studies in order interrogate the “real” and reality facing Europe’s refugee crisis, with “real” being that which is constructed for ideological gains and reality is on the surface, yet hidden from plain sight. There are two main arguments here: First, by addressing issues that are hidden from the public view, Threads challenges those who engage in victim blaming and encourages readers to take responsibility without reducing the human subjects to objects of pity. And second, at a time when curriculum choices are influenced by media coverage, and right-wing fundamentalist and anti-immigrant groups are flooding social media and other public spaces with negative stereotypes that rob the disenfranchised people of their dignity, Threads restores it back. Threads has the potential to alter the classroom into a radical space or what Nancy Fraser’s calls a “subaltern counterpublic” by forcing students to critically answer questions like: What role does Europe play in creating the refugee crisis? why is the concept of “worthy” refugee problematic? And, who profits from this practice, even if the end result is death?

|

|

Reshmi Mukherjee is an Assistant Professor of English at Boise State University. She holds a PhD in Comparative and World Literature from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and an M.Phil degree in Women's Studies from Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India. Her research and teaching focus on representations of race, gender, sexuality, and subalternity in literatures of the global South, with particular interest in diasporic, exilic, testimonio, and refugee narratives. Her area of specialization is postcolonial theory, transnational feminism, and culture studies. Her publications have appeared in Boundary2, Toronto Quarterly, and South Asian Review.

|