ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

2.2

2.2

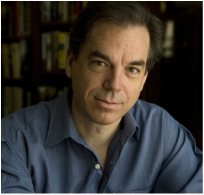

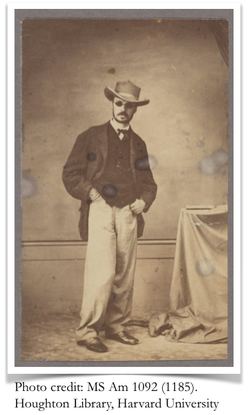

In a photograph he posed for during a journey to Brazil in 1865, William James looks every bit the rugged adventurer. With his Panama hat, cooler-than-thou sunglasses and air of unkempt elegance, he comes off as the gritty forefather of bohemian globetrotters such as George Orwell, Eric Newby, Isak Dinesen, Freya Stark, Paul Theroux, Jon Krakauer and Sebastian Junger. But as James himself would have said—indeed, as he built a whole career out of saying—first impressions can be deceiving, especially when it comes to the inner lives of other human beings.

Born in New York in 1842, James had a nomadic upbringing. Thanks to an eccentric and impulsive father, who was too restless to embrace a stable life and too rich to need one, the future philosopher’s childhood was comprised of a series of back-and-forth voyages between Europe and the United States. By the time he was 16, William James had lived in at least 18 different houses—and that’s not counting his family’s numerous lengthy stays in hotels of various cities (Richardson, William James 19). His brother, the future novelist Henry James, embraced this peripatetic lifestyle. Describing himself as a “visionary tourist” (H. James 103), he would later populate his fiction with transatlantic wanderers and write several travel books. The young William James, by contrast, wearied of life on the move. At age 16, he confided to a friend: “We have now been three years abroad.… I think that as a general thing, Americans had better keep their children home” (qtd. in Richardson, William James 24). He would grow up to become one of the foremost thinkers of his age—father of modern psychology, influential philosopher, friend and mentor of the civil-rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois—but he would remain an ambivalent traveler, and sometimes a very whiny one. His one great adventure came at age 23, when he joined a scientific expedition to the Amazon. For James, who left Harvard Medical School to sign up for the journey, it was a disaster from the start. “For twelve mortal days,” he wrote of the passage to South America, “I was, body and soul, in a more indescribably hopeless, homeless and friendless state than I ever want to be in again” (W. James, Letters from Brazil 53). Despite his jaunty appearance in that photo, he found Brazil “so monotonous in life and in nature that you are rocked into a kind of sleep” (W. James, Letters from Brazil 85). He discovered that he hated collecting scientific specimens—the whole point of the expedition—and that he hated mosquitoes even more. He came down with a form of smallpox, which caused him chronic vision problems for the rest of his life. (The sunglasses, it turns out, were apparently not a fashion statement.) The expedition—which took him 2,000 miles up the Amazon and 2,000 miles back, often under dangerous conditions—left him convinced he wanted to lead a speculative rather than an adventurous life. “When I get home,” he wrote, “I’m going to study philosophy all my days” (W. James, Letters from Brazil 60). But in at least one important respect, the trip seems to have had a positive and lasting effect on James. It forced him to begin asking questions about the degree to which outsiders—privileged travelers, as we sometimes call them today—can ever know about the people and places they visit. Is it possible to understand lives that are fundamentally different from our own? How do we separate our own preconceptions and prejudices from the events we witness and the individuals we encounter? Can we ever say anything definitive about an unfamiliar culture? In the 150 years since William James went on that expedition, air travel has made the journey to Brazil simple and relatively painless, economic integration has landed Walmart on the streets of Rio de Janeiro and the internet has brought Amazon.com.br to online shoppers deep in the rainforest. But a funny thing happened on the way to the Global Village. Far from uniting the world, the shrinkage of space and time has only seemed to widen cultural differences. ___________

I live in one of the most segregated cities in the United States. In Chicago, it’s not unusual to meet people who have been all over the world—Europe, Asia, South America, even Africa—but have never set foot in certain neighborhoods a few miles from their homes. Race plays a huge role in our divisions, of course, but it’s more complicated than that. In addition to being the most demographically divided city in the country, Chicago also happens to be one of the most diverse. If you go a mile to the west of my mostly white, mostly middle-class community, you’ll be in a Korean neighborhood, where the local grocery store stocks steamed pigs’ feet, acorn powder, melon milk and yam cake. If you go a mile to the northwest, you’ll be in an Orthodox Jewish neighborhood, where bearded men walk around on the Sabbath in shtreimels—huge fur hats, shaped like horizontal car tires. If you go four blocks straight north, you’ll be in a sprawling Indian and Pakistani neighborhood, full of high-end sari shops and halal meat markets and crowded restaurants redolent with turmeric, cardamom, coriander, cumin and fenugreek. For the most part, the Hindu and Muslim residents of this community seem to get along, but the place is riddled with invisible fault lines. David Coleman Headley, a Pakistani-American convicted of helping to plan the 2008 terrorist attacks that left 164 people dead in Mumbai, India, lived not far up the street from me. His accomplice, Tahawwur Hussain Rana, also resided nearby.

Increasingly, it’s those invisible fault lines that interest me as a writer—the borders that divide us, even as the instantaneous movement of information collapses geographic boundaries. In previous eras, much of what readers learned about other cultures came from travel writers, such as the "visionary tourist" Henry James. But in an age of global mobility, with the number of international migrants now exceeding 250 million, the world melts into a scrambled landscape of Salvador Dali: HereThereUsThemNearFarInsiderOutsider. These days, all writers are travel writers. And that’s exactly why we must listen to an adventurer who wished he’d never left home. __________

William James is still remembered for a distinctively non-linear prose style, in which he juxtaposes various voices of other writers and invites readers to make their own connections and draw their own conclusions. He does this to stress “fluidity, indeterminacy and multiplicity” as well as to “challenge innumerable concepts that he feels are too rigid or too static” in the words of Frederick J. Ruf, author of The Creation of Chaos: William James and the Stylistic Making of a Disorderly World (Ruf xvii). In an attempt to both embrace and make sense of the philosopher’s method, I have chosen to employ a similar style in this essay, even if it risks sacrificing (to quote one of James’ critics) the “rigorous sequence [and] progressive development” usually found in an academic publications in favor of (to quote another) “meandering, zigzags and circles” (qtd. in Ruf xviii).

It’s an approach to writing that even bothered the man who, along with James, is credited with helping us to see the universe as a place where events are uncertain and perception is imperfect. “Philosophy,” the logician Charles Sanders Peirce once wrote to James, “is, or should be, an exact science, and not a kaleidoscopic dream” (qtd. in Bordogna 261). But William James had come back from Brazil with a growing distrust of the whole notion of exactitude. The expedition was organized by Louis Agassiz, one of the leading scientists of his day and a fierce opponent of Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, published just six years earlier in Origin of Species. Agassiz, in the words of one biographer, “was what would now be called a creationist. Different species were created at different times and places in a choreographed fulfillment of a complex and preordained master plan” (Richardson, William James 48). The “chief aim” of the trip, Agassiz declared, was to disprove Darwin’s theory (Agassiz 33), in part by demonstrating that fish collected from two isolated river systems were distinct from each other and not evolutionary variations. He came back with 80,000 specimens—including 50 barrels of crayfish alone—but his boast that the expedition marked “the end of Darwin” (qtd. in Dobbs 95) did little to convince the growing number of doubters in Agassiz and his ideas. Those skeptics included William James, who, by 1868, was describing his mentor as a “scoundrel…unworthy either intellectually or morally for [Darwin] to wipe his shoes on” (qtd. in Menand 142). Particularly problematic to James was the older scientist’s belief in polygenism—the theory that humans of different races are descended from different ancestors and that God endowed these separate “species” with unequal aptitudes. Like many people of his time and social milieu, James himself sometimes made reference to “inferior races” (qtd. in Menand 145), but the expedition forced him to rethink those assumptions. After observing the complex social interactions of Native Americans in isolated villages along the Amazon—people whose manners and “urbane polite tone of…conversation” were equal to any “gentleman of Europe”—the future philosopher came up against a fundamental question (W. James, Brazilian Diary 90). “Is it race or is it circumstances” he asked himself, which determines someone’s behavior? He could see that Agassiz had already formulated an answer long before he left for Brazil—and that his conclusion was hardly the result of scientific rigor. At one point, James walked in on a photo session at which Agassiz induced local women to "strip and pose naked" (W. James, Brazilian Diary 88). The famous scientist insisted his photographs of women’s breasts—an extensive collection, it later turned out—were being compiled in the name of research, a claim that James clearly doubted. Even the camera—a 19th-century invention that promised an objective view of reality—could not transcend the blindness, prejudices and perhaps sexual fetishes of the photographer.

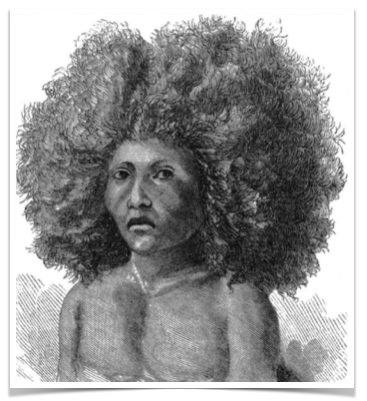

William James, by contrast seemed to be losing interest in the very idea of objective views. A gifted artist with some formal training, he was at one point instructed by Agassiz to sketch a young woman whose “mixture of Negro and Indian blood is a rather curious illustration of the amalgamation of races” (Agassiz 246). Intentionally or not, James imbued this “specimen” with a fierce sense of selfhood. In a woodcut made from that drawing, the woman, a housemaid named Alexandrina, stares at modern viewers, just as she must have stared at William James, with a complex gaze—sad, defiant, passionate and intelligent—a gaze that defies simple understanding.

Louis Agassiz went to Brazil to prove that his way of seeing was the only correct one. William James came home from that trip with doubts that any single way of seeing could be correct at all times. These doubts would grow into an entire school of philosophy: pluralism. __________

Last night, I took my children out for ice cream at a local drive-in called Dairy Star. With its picnic tables and U.S. flag and kitschy sign featuring a giant soft-serve cone, the place is in many ways an icon of 1950s WASP Americana. But a closer look at that sign reveals a small triangle containing the letters CRC—the Chicago Rabbinical Council’s seal of approval.

As we got out of the car, young men in yarmulkes and side curls watched us through a chain-link fence as they gathered at the religious school next door. The customers at Dairy Star comprised a wild cross-section of Chicagoans and suburbanites—whites, African-Americans, Latinos, Christians, Muslims, Jews, all of us gathered on the first warm night of the year for a taste of delicious kosher soft serve. Sixty-five years ago, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss famously declared an end to the “time when travelling brought the traveler into contact with civilizations which were radically different from his own” (Lévi-Strauss 86). Like William James, Lévi-Strauss returned from a scientific expedition to Brazil ambivalent about the entire enterprise. (Tristes Tropiques, his account of that journey, begins: “I hate travelling and explorers” [3]). He came back to France convinced that “whether he is visiting India or America, the modern traveler is less surprised than he cares to admit” (86).

That may be true, but it’s also true that on a journey to the local drive-in the traveler can be more surprised than he cares to admit. As I sat with my kids at Dairy Star last night, I found myself staring at a fellow customer, a Muslim woman wearing a niqab—the kind of veil that covers everything but the eyes. For a fraction of a second, she glanced back at me with a look I couldn’t begin to fathom. Was it useless to try to make sense of this moment? Did my status as an outsider (even in my own neighborhood) and a white man (even though I’m married to a woman of Muslim heritage) prevent me from exploring it on the page? Did my own biases (including my unfavorable view of the niqab as a means of subjugating women) negate my powers as a narrator? Was the gap between that woman and me (only a few yards in physical space) simply too wide to bridge?

__________

Pluralism—a term William James introduced to English-language philosophy—is based on the notion that an outsider’s understanding of another person is always partial and provisional. Rather than imposing a single, absolute, objective standard of truth, pluralism stresses that our view of reality is always influenced by our cultural and historical context. James articulated many of his most important ideas about this concept in an 1899 essay, “On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings.” The biographer Robert D. Richardson—who may be more familiar to readers of Assay as Annie Dillard’s husband—has described this short treatise as deserving “a place among the defining documents of American democracy” (Richardson, Introduction 145). As Richardson points out, the word “empathy” did not appear in the English language until 1909—a decade after James published his famous essay. But if “On a Certain Blindness” was ahead of its time, it has also aged amazingly well. Its basic message that “the clamor of our practical interests” makes us "blind and dead…to all other things” (W. James, “On a Certain Blindness” 155) seems even more relevant in the 21st century when that clamor is louder than ever, exponentially amplified by the internet, cell phones, social media and 24-hour news.

Lately I find myself returning to this essay again and again—to learn from the philosopher, as well as to argue with him on certain key points. The central episode in “On a Certain Blindness” comes from a journey William James took through the mountains of North Carolina, where he witnessed large swaths of what we would today call clear-cutting—countless charred stumps where beautiful trees had once stood. “The forest had been destroyed,” he writes, “and what had ‘improved’ it out of existence was hideous, a sort of ulcer… No modern person ought to be willing to live a day in such a state of rudimentariness and denudation” (147-148). But James soon discovered that these initial impressions—which had seemed so self-evident to him—were based on his own presuppositions. He describes his moment of epiphany: I said to the mountaineer who was driving me: “What sort of people are they who have to make these new clearings?” “All of us,” he replied; “why, we ain’t happy here unless we are getting one of these coves under cultivation.” I instantly felt that I had been losing the whole inward significance of the situation. Because to me the clearings spoke of naught but denudation, I thought that to those whose sturdy arms and obedient axes had made them they could tell no other story. But, when they looked on the hideous stumps, what they thought of was personal victory. The chips, the girdled trees, and the vile split rails spoke of honest sweat, persistent toil and final reward. The cabin was a warrant of safety for self and wife and babes. In short, the clearing, which to me was a mere ugly picture on the retina, was to them a symbol redolent with moral memories and sang a very pæan of duty, struggle, and success. (148) The privileged traveler had, it seemed, completely misunderstood the situation. Or had he? With hindsight, the truth seems more complicated. Due to the clear-cutting practices James witnessed in the late 1800s, for instance, it’s now estimated that only about one half of one percent of the old-growth forests in the Southeast are still standing (National Commission on Science for Sustainable Forestry 12). To cite just one example, North Carolina’s Mount Mitchell—the highest point east of the Rockies, where William James took “the most beautiful forest walk…I ever made” (W. James, Essays 133)—was almost completely cleared of trees in the early 1900s as a result of industrial logging and consequent wildfires (Silver 144-148). More than a century after the philosopher published his famous essay, it seems that his initial understanding of what he witnessed was far less rash, and far more prescient, than he could have realized at the time. He may not have understood the “inward significance of the situation”—but in this one case, at least, his first impressions about the outward significance proved to be exactly right.

“The spectator’s judgment is sure to miss the root of the matter and to possess no truth,” James argues in “On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings” (147). But this assertion strikes me as too categorical, especially coming from a philosopher who distrusted absolutes. True, we must strive to be aware of “the stupidity and injustice of our opinions, so far as they deal with the significance of alien lives” (146). But often the outsider’s view—no matter how provisional, incomplete and oblique—turns up clues that, to the insider, seem so familiar as to be unworthy of notice. __________

In this era of jumbled geographies and invisible borders, two types of writers seem to thrive. I like to think of them as the inside outsider and the outside insider. One of the most astute essays about my own hometown was written by an unapologetic outsider—the British writer G.K. Chesterton. A curmudgeonly wanderer—“I have never managed to lose my old conviction that travel narrows the mind” (Chesterton 37)—who could be particularly cantankerous when it came to the United States, Chesterton visited Chicago briefly in 1930, during the height of the gangster era. Local newspapers in those days were full of blood and gore and body counts. But Chesterton was able to look beyond these screaming headlines to see what the insiders were unable to see—that technology was fundamentally altering the situation on the streets of Chicago.

The kind of privilege that Chesterton and other outsiders benefit from involves not only a freedom of space (the wealth and mobility necessary to visit foreign cultures) but also a freedom of time (the leisure, learning, solitude and silence required to resist the frenzy of the moment). And in the age of the Internet—when we now receive, and must attempt to wrap our heads around, five times as much information every day as we did in 1986 (Levitin)—this latter kind of privilege has taken on an added importance, precisely because it’s an increasing rare commodity. In an essay published in The New York Times Magazine in 1931, Chesterton noted a sudden paradigm shift in power relations between governments and criminal groups: In the advanced, inventive, scientifically equipped and eminently post-Victorian city of Chicago the criminal class is quite as advanced, inventive and scientifically equipped as the government, if not more so. If our modern society is breaking up, may it not break up into big organizations having all the armament and apparatus of independent nations; so that it would no longer be possible to say which was originally the lawful government and which the criminal revolt? ... That is the significance of the criminal with the machine gun: that he has already become a statesman; and can deal not in murder but in massacre. (Chesterton 534) In a couple of stunningly prescient paragraphs, Chesterton managed not only to make sense of Al Capone’s fedora-wearing thugs but also to anticipate the masked assassins of ISIS. As an outsider, Chesterton was removed enough from the day-to-day slaughter in Chicago’s alleyways to notice larger patterns that insiders were unable to perceive. And because of this advantage, he was able to offer insights into not only the present but also the future.

In a recent New Yorker article about his travels in China, Peter Hessler notes that he might have had an advantage over his native counterparts because, for them, “the relentless pace of life in China made it hard to document details.” He recalls a conversation with a local journalist, who told him, “Sometimes in China you have this feeling of suffocation, and it’s hard to notice all these things. Maybe because you’re a foreigner, you can be a little separate. Maybe it’s easier to be still. We have a phrase, yi bubian ying wanbian—you cope with change by staying the same. If you don’t move, then you notice everything moving around you” (Hessler, “Travels with My Censor” 36). Sometimes travel writers of the Information Age must stand still. Sometimes they must not travel. Sometimes they must stay home and sit in the dark as if “imprisoned or shipwrecked,” as James puts it in his farsighted essay. In stasis and silence, “the good of all the artificial schemes and fevers fades and pales; and that of seeing, smelling, tasting…grows and grows” (W. James, “On a Certain Blindness” 160). Hessler is an example of the inside outsider, a writer who combines an outsider’s perspective with an insider’s nuanced understanding of the culture. Raised in Missouri and educated at Princeton and Oxford, he went to China as a Peace Corps volunteer in the mid-1990s, and remained there as Beijing correspondent for the New Yorker from 2000 to 2007. Fluent in Mandarin, he moved into an apartment building off a tiny alleyway—or hutong—in downtown Beijing, where he did his best to assimilate into the local population. In this 2006 essay, “Hutong Karma,” he describes how a new public toilet affected the communal culture of the hutong as the Chinese government prepared to host the 2008 summer Olympics: The change was so dramatic that it was as if a shaft of light had descended directly from Mt. Olympus to the alleyway, leaving a magnificent structure in its wake. The building had running water, infrared-automated flush toilets, and signs in Chinese, English, and Braille. Gray rooftop tiles recalled traditional hutong architecture. Rules were printed onto stainless steel. “Number 3: Each user is entitled to one free piece of common toilet paper (length 80 centimetres, width 10 centimetres).” … [Local] residents took full advantage of the well-kept public space that fronted the new toilet. Old Yang, the local bicycle repairman, stored his tools and extra bikes there, and in the fall cabbage venders slept on the strip of grass that bordered the bathroom. Wang Zhaoxin, who ran the cigarette shop next door, arranged some ripped-up couches around the toilet entrance. Someone else contributed a chessboard. Folding chairs appeared, along with a wooden cabinet stocked with beer glasses. After a while, there was so much furniture, and so many people there every night, that Wang Zhaoxin declared the formation of the “W. C. Julebu”: the W. C. Club. Membership was open to all, although there were disputes about who should be chairman or a member of the Politburo. As a foreigner, I joined at the level of a Young Pioneer. On weekend nights, the club hosted barbecues in front of the toilet (Hessler, "Hutong Karma" 84). As a five-year resident of the community, Hessler knew his neighbors well enough to gain at least partial acceptance as a “Young Pioneer.” Even that title—which refers to a mass organization for children, run by the Communist Youth League—suggests local residents were comfortable enough with the American to include him on an inside joke. Yet he also had enough of an outsider’s perspective to see how the small events near his alleyway were connected to larger forces in the global economy. Within a few years of the arrival of that new toilet, Hessler observes, “bars, cafés and boutiques” (89) began moving into the neighborhood, uprooting local residents and slowly eroding the communal culture. The essay ends with Wang Zhaoxin, the founder of the W.C. Club, walking through a building he had called home since 1969, now scheduled for demolition. “That’s where my father slept,” he says, pointing to an empty room. “My brother slept there” (89). In this poignant moment, I suspect even William James might agree that Hessler gives readers a glimpse into “the vast world of inner life beyond us” (W. James, “On a Certain Blindness” 152).

For the inside outsider, the risk of staying in one place for so many years “is that you can get too focused and lose perspective on where that corner of the world fits into the larger picture,” as Hessler himself once noted in an interview (Potts). This appears to be a primary reason he decided to leave China in 2007. Since 2011, he has lived in Cairo, where he has been learning Arabic and immersing himself in the local Egyptian culture—an inside outsider once more. Some authors, however, manage to stay home and write about the place they know best without internalizing local assumptions and prejudices. William Kittredge, who grew up on a sprawling ranch his family owned in the Warner Valley of southeastern Oregon and has spent most of his adult life in Montana, is one such outside insider—"both a native with sound redneck credentials and an academic/environmentalist," in the words of the Los Angeles Times (Duane). Kittredge’s 1996 collection of essays, Who Owns the West?, begins like this: On May 14, 1988, I watched a parade of 330 logging trucks, each loaded with fresh-cut timber, head out on a parade through the small country towns of the Bitterroot Valley in Montana—Lolo to Florence, Victor to Hamilton, and on to Darby in the backlands country near the Idaho border. They were hauling 1.5 million board feet of saw-logs to the Darby Lumber Company Mill, which was threatening to close. … Country citizens gathered along the roadside to watch and wave and cheer. Called the Great Northwest Long Haul, that parade got started up the road in northwestern Montana around Libby, where milling logs is not just a major industry but a way of life. It ended sometime after three o’clock in the morning with a street-dance celebration (Kittredge 3). A century earlier, Williams James had encountered a similar collection of “country citizens,” to whom logging was, as he put it, “a symbol redolent with moral memories and sang a very pæan of duty, struggle and success” (148). But unlike James, Kittredge has never been blind to the “inward significance” of those people’s lives. He’s spent his life around Westerners who depend on logging for their livelihoods. He’s driven past the backroad signs that proclaimed THIS FAMILY SUPPORTED BY THE TIMBER INDUSTRY (3). And he has a deep understanding of the resentments they feel about the fast-changing economy that threatens their way of life:

The old economic order in the West is right to fear environmentalists and others who understand the West as a place to be preserved, not used; the newcomers are going to prevail in the long run; they represent the will of the nation; they have demographics on their side. ... A lot of locals, former loggers and miners and such, are likely to end up in the servant business, employed as motel clerks and hunting guides, and they know it. It’s not hard to figure out why many people in the Rockies hate this wave of outlanders with such a passion. (134, 140) Like the inside outsider Peter Hessler, Kittredge is able to use his perspective as an outside insider to offer a nuanced picture that neither the locals nor the “outlanders” could perceive. Although two decades have passed since its publication, Who Owns the West? remains a strikingly relevant exploration of rural anger and alienation—a redneck rage that, in the years since, has coalesced around the Tea Party movement and right-wing militia groups, one of which, as this essay goes to press, has taken over a federal wildlife refuge not far from the ranch where Kittredge grew up. The author of Who Owns the West?—who warned in 1996 that a number of his fellow Westerners were growing "deeply paranoid" and "band[ing] together" in "small political entities" (6)—may have more in common with environmentalists than with "gun-packing men on the streets of obscure little towns in Idaho and Montana, dropping hints about revenge if they can’t have justice" (4). But he sees why they "feel, quite justifiably, cut off from the sources of power in their culture" (93) and he believes the writer’s job is to help bridge that divide. "We need stories," he writes, "that will encourage us toward acts of the imagination that in turn will drive us to the arts of empathy, for each other and the world" (164).

But are there limits to those arts of empathy? Can pluralism make any real sense out of an ideology that is radically anti-pluralist, a belief system that violently disavows the legitimacy of any truth other than its own? Can William James help us come to grips with “Jihadi John,” the masked master of ceremonies on several ISIS videos that depict the beheadings of American journalists and other hostages?

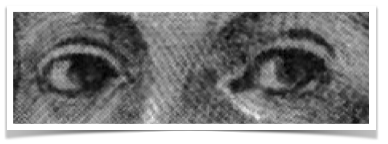

When I look into those eyes, I think of a recent essay about “the mind of a mass killer” by the Norwegian novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard. “The most powerful human forces are found in the meeting of the face and the gaze,” Knausgaard writes. “Only there do we exist for one another. In the gaze of the other, we become, and in our own gaze others become. It is there, too, that we can be destroyed. Being unseen is devastating, and so is not seeing” (Knausgaard 32).

James warned of the dangers of attempting to see; Knausgaard is interested in the consequences—potentially even more profound—of turning away. The subject of his study is right-wing terrorist Anders Behring Breivik, who killed 77 people in car-bomb and shooting attacks in Norway on July 22, 2011. In a 1,500-page manifesto he sent out just before the slaughter, Breivik claimed to be at war with Muslims. Nonetheless, he seems to have a great deal in common with Jihadi John, aka Mohammed Emwazi, a former London schoolboy whom U.S. officials killed in a drone strike in 2015. Both young men were apparently obsessed with martial arts, video games and hate sites in the blogosphere (anti-Muslim for Breivik, anti-Western for Emwazi). Both also developed a deep contempt for pluralism, a hatred for diversity and difference, an intolerance for those they viewed as the other. Knausgaard’s description of Breivik’s process of alienation might also apply to Emwazi: [He] remained unseen, and it destroyed him. He then looked down, and he hid his gaze and his face, thereby destroying the other inside him. ... The fact that he did what he did, and that other young men, misfits, have shot scores of people, implies that the necessary distance from the other is attainable in our culture, probably more so now than it was a couple of generations ago. (32) Like William James, Knausgaard believes that there’s a limit to what we can know about another human being: “Breivik’s childhood explains nothing, his character explains nothing, his political ideas explain nothing” (31). What does explain the killer, according to Knausgaard, is his inability to “see” (that is, a failure to acknowledge the humanity of others), as well as his sense of being “unseen” (that is, a perception that his own humanity was overlooked by others).

He wanted to be seen; that is what drove him, nothing else. ... And that is perhaps the most painful thing of all, the realization that this whole gruesome massacre, all those extinguished lives, was the result of a frustrated young man’s need for self-representation. (30) So how do we succeed in seeing other people—and how do we find ways to feel seen—in an age when everyone’s eyes are constantly diverted by cell-phones, social media and a host of other digital distractions? Knausgaard concedes that there are no easy answers:

We all move between fiction and reality, between image and material, and the distance to the other is no straightforward quantity, and neither is the act of averting one’s gaze. In order to see the culture, one must stand outside it; in order to see the individual, one must stand outside him (32). The only certainty is the need to look. Even into eyes that don’t want to be seen. Even into eyes that seem impenetrable. Even into eyes that stare back with hate—especially those eyes.

___________

The notebooks William James kept during his expedition to Brazil contain a curious self-portrait of the future philosopher, smoking a pipe and slouching in an easy chair. It’s as if the homesick adventurer was trying to imagine himself right out of the Amazon, with its swarms of mosquitoes and swampy ethical dilemmas, and back into his familiar world of wealth, safety, status and certainty. James made it back home from Brazil, of course, back to his world of privilege, but he never quite saw privilege the same way again. His work—and that of his followers, W.E.B. Du Bois, John Dewey, Jane Addams and Alain Locke—would help future generations understand that race, class and gender are largely social constructions. Privilege is not static or biological; it’s something humans beings have invented—and something human beings can always reinvent.

So perhaps it’s time to come up with a new understanding of the privileged traveler. There are, after all, two definitions of privilege—one associated with entitlement, advantage, authority, even immunity; the other associated with respect and deference. When I say, for example, that I feel privileged to be in the presence of someone who is different than me, I am not suggesting that I am superior to that person. Quite the opposite: I am asserting that I am enriched, intellectually and emotionally, by the encounter. And implicitly, at least, I am acknowledging the other individual’s intelligence, spirit, dignity and humanity.

On a recent book project, I tried to be guided by this more inclusive idea of privilege. In 2011 and 2012, while more than 900 people were being murdered on the streets of Chicago, my creative-writing students at DePaul University and I fanned out all over the city to interview people whose lives had been changed by the bloodshed. We spoke to kids in gangs, kids risking their lives to stay out of gangs, parents and siblings who’d lost loved ones to street violence and adults who’d been part of that violence and now must live with their actions. We spoke to cops, local activists and members of the clergy. We spoke to an emergency-room nurse, a funeral-home director and the county coroner. Chasing down these stories involved the crossing of countless invisible borders, with students often going into neighborhoods they’d never even heard of before, much less visited. Those who had grown up in violence-plagued communities served as outside insiders (a role that altered classroom power dynamics in exciting ways). The others did their best to become inside outsiders, often with impressive success. The resulting collection of oral histories, How Long Will I Cry?: Voices of Youth Violence. The book is grounded in “collaborative storytelling,” an ancient form, enhanced by new technologies, in which individual stories form larger narratives, which in turn inspire more people to share their own experiences. People who lent their life stories to the project were partners in the creative process. They had editorial control over their narratives, and they played a starring role in book events. On a tour through Chicago Public Library branches in communities where killings are common, actors from the renowned Steppenwolf Theatre did staged readings, after which the real-life protagonists joined them onstage to answer questions and sign books for audience members. Since then, we’ve gone through four editions more than 25,000 copies nationwide, many of them finding their way to the hands of nontraditional readers, including at-risk youth and prison inmates. In Chicago, the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center is using How Long Will I Cry? in a book club, where a caseworker reports that it “has changed the lives of these young men and women” (Harvey xii). In Houston, an official at another juvenile detention center reports that the book has helped create “empathy in the residents within our facility. … They seem to develop a greater insight into the impacts of their actions on their families, their neighbors and their greater communities” (Harvey xi). Readers who live in safe and prosperous places, meanwhile, report a new compassion for residents of violence-plagued neighborhoods. In some small way, the book is helping readers to see, to be seen, to grapple with, as William James puts it, “the inner significance of lives different from our own.” ___________

As I come to the end of this essay, I realize an embarrassing irony: to support my arguments about pluralism, I’ve quoted a bunch of other white men. William James would not have been surprised. We are all blind, he insisted, even when we attempt to see. And because of this fundamental fact of our humanity, all efforts to understand other people—whether at the local drive-in, in distant lands or in wilderness of cyberspace—come with grave responsibilities:

It absolutely forbids us to be forward in pronouncing on the meaninglessness of forms of existence other than our own; and it commands us to tolerate, respect, and indulge those whom we see harmlessly interested and happy in their own ways, however unintelligible these may be to us. Hands off: neither the whole of truth, nor the whole of good, is revealed to any single observer, although each observer gains a partial superiority of insight from the peculiar position in which he stands. (W. James, “On a Certain Blindness” 162-163) William James’ journey to Brazil, observes the historian Maria Helena P.T. Machado, may have been full of “suffering and deprivation,” but it was marked by one great personal breakthrough: “the first discovery of the other” (Machado 48). James devoted the rest of his career to mapping that discovery. Travel writers of the 21st century would do well to follow those maps, even though, as the cartographer himself would assure us, they will always lead us to terra incognita.

|

Click here to download the PDF with Works Cited.

|

Miles Harvey is an associate professor of English at DePaul University, where he teaches creative writing. He is the editor of a collection of oral histories, How Long Will I Cry?: Voices of Youth Violence and the author of a play, also called How Long Will I Cry?, which premiered at Chicago's Steppenwolf Theatre in 2013. His previous work includes The Island of Lost Maps: A True Story of Cartographic Crime (Random House), a national and international bestseller that USA Today named one of the ten best books of 2000, and Painter in a Savage Land: The Strange Saga of the First European Artist in North America (Random House, 2007).

|

Related Works

|

Lynn Z. Bloom

Why the Worst Trips are the Best: The Comic Travails of Geoffrey Wolff & Jonathan Franzen 1.2 Articles |

Bernice M. Olivas

Politics of Identity in the Essay Tradition 2.1 Pedagogy |