ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

8.1

8.1

|

For there are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt.

-- Audre Lorde, “Poetry is not a Luxury”

|

|

this is how you sweep a corner; this is how you sweep a whole house; this is how you sweep a yard; this is how you smile to someone you don’t like too much; this is how you smile to someone you don’t like at all; this is how you smile to someone you like completely; this is how you set a table for tea; this is how you set a table for dinner; this is how you set a table for dinner with an important guest; this is how you set a table for lunch; this is how you set a table for breakfast; this is how to behave in the presence of men who don’t know you very well, and this way they won’t recognize immediately the slut I have warned you against becoming…

|

“Girl” is presented as a solid wall of words. Both the appearance and the content of the text are heavy. But what happens when this same piece is formatted like a “traditional” poem, if it has line breaks?:

|

this is how you sweep a corner;

this is how you sweep a whole house; this is how you sweep a yard; this is how you smile to someone you don’t like too much; this is how you smile to someone you don’t like at all; this is how you smile to someone you like completely; this is how you set a table for tea; this is how you set a table for dinner; this is how you set a table for dinner with an important guest; this is how you set a table for lunch; this is how you set a table for breakfast; this is how to behave in the presence of men who don’t know you very well, and this way they won’t recognize immediately the slut I have warned you against becoming; |

By pressing “return” whenever Kinkaid uses punctuation, I’ve altered the shape of the narrative. But the experience of reading it changes, too. “Girl” now unfurls; there is air in this stretched-out version, and this air makes the recurring use of “This is how you/ This is how to” seen before it is read. The text looks like ribbons. When done to the whole piece, “Girl” also takes up space differently, carrying over onto a second page, whereas the actual version is compact, one page, no more space than it needs to take up. And all of this—the air, the visual pattern, the spilled space—contradict the message of the piece. “Girl” is not about beauty or airlessness, it is not about a young woman becoming something new or free. It is about women who are not to move beyond very specific parameters. It is about the rigidity of caretaking, and reputation. And so, when reading “Girl” the way it actually looks, that is, like a solid square of words, the weight is felt, dense. In a piece about the places Antiguan women occupy, it becomes clear, by seeing this wall of words, that women are not to be taking up space. In a piece about being boxed into the role of girl, of woman, of wife, of daughter, of virgin, the narrator and the girl she speaks to are literally boxed. The weight is suffocating. Is there a way out? No.

Part Two: How Use of Page Space Reflects Women’s Place

The ability to tell your own story, in words or images, is already a victory, already a revolt.

--Rebecca Solnit, Men Explain Things to Me

--Rebecca Solnit, Men Explain Things to Me

I. Page space examples: On roots and foundations

What is function of page space? How does it impact narrative movement and reader understanding? And what might the cultural implications of this type of writing be? In Robert Root’s book The Nonfictionist’s Guide: On Reading and Writing Creative Nonfiction, he notes, “The white spaces on the page—the page breaks or paragraph breaks—are part of the composition. They serve as fade-outs/ fade-ins do in films, as visual cues that we have ended one sequence and gone on to another.” But to say that these breaks serve as fade-outs/ fade-ins ignores the fact that there is also drama in these gaps. A gap on the page is visually starker than a transitional phrase linking two paragraphs. Page space, when it appears in nonfiction, is cinematic and theatrical.

In 2018, Caroline Hagood wrote a book-length lyric essay titled Ways of Looking at a Woman, wherein she meditates on what it means to be a mother, a woman, a scholar, and an object of the male gaze. Hers is a book presented like a doctoral thesis; the sections are titled “Research Proposal,” “Abstract,” “Methodology,” etc. and within these sections she writes about literary theory, motherhood, television, and the joy of writing poetry in movie theatres.

Her paragraphs are blocks separated by thin lines of space instead of indents. When she shifts ideas, they are marked with a single tiny star. After a star appears, there is only the gap of page space; her next thought doesn’t appear until the following page. Some paragraphs appear like they are floating, because this space creates a sense of air, or breathing. To read her work is to feel that in-between her discourse, she is (we are) blinking. These spaces allow for an exhalation and a meditation before reader (and writer) move forward. The effect here is of dropping, an idea is presented and given room to be pondered, or, perhaps, like I did, the reader is given the space to write down her ideas, her own thoughts, about Hagood’s points. A conversation, perhaps, though completely private, and filled with the drama of two friends engaged in something profound. It has the effect of watching a film so intense and beautiful you forget to breathe, but here, she stops to remind her reader to exhale, then inhale again. It is sitting alone in a theatre, with the space to think quietly about what is being shown.

Though I know men use gaps in their writing, too (Robert Root provides a thorough list of male essayists who utilize the page this way,) I can’t help but think there is something about women using page space that might be different. Root explains that “Such writing demands that the reader learn to read the structure of the essay as well as its thought. That is the task for which the twentieth-century reader is well prepared, because the episodic or segmented or disjunctive sequence is a familiar design in many other genres” (Root 77). We are used to consuming information in tweet-sized bites. So perhaps when writers write in segments and use page space, it is done to cater to the reader. But I think this form goes beyond writing for the modern reader’s fragmented way of thinking. It is reflective of the thought process of the writer as well. Is the thought of the women-writer essayist fragmented? Is it concerned with the way it takes up space?

I think, in part, especially when page space is used as a way to draw attention to injustice or political pain, (as we will see in Tyrese Coleman’s How to Sit, in Dana Tommasino’s essay “birdbreath, twin, synonym,”) it is fair to consider page space in a similar way to how fourth wave feminists think about and use technology—how activism is promoted and spread through platforms like Twitter. These pieces use page space to draw attention to larger issues, beyond the story as well as within it. And yet, in other works, especially slightly older works, like Vivian Gornick’s Fierce Attachments, the page space is not a statement as much as it is a time marker, a pathway, a noticeable hole to think about space. Page space works in many ways, it shifts its tone and meaning. It reminds me of the way I think, that is, after a burst of an idea, I need quiet to consider what happened and what might happen next.

Tyrese Coleman’s How to Sit, is a memoir told in stories and essays; a blending of fiction and nonfiction. In the note from the author, Coleman explains how she is challenging the distinction between memory and truth: “This collection, a memoir when viewed in its entirety, plays with the line between fiction and nonfiction as it explores adolescence, identity, grief, and the transition between girlhood and womanhood for a young black woman seeking to ground herself when all she wants is to pretend the world is fantasy” (Coleman). In “playing with the line between fiction and nonfiction,” Coleman is thinking about division, about separation. And when there is separation, a gap appears. For Coleman, this is represented on the page as well.

When she begins telling her story, Coleman’s paragraphs are separated by chunks of page space. Furthermore, in some of these gaps, those that beg the reader to stop for just a little bit longer, there is a short horizontal line. The page space and lines within that space serve as a reminder not only of the memoir’s hybridity, (in fact there is no way to know what is fiction and what is non, know way to know what is “the truth” because it all is,) but of division, of divisiveness. Page space, it seems, is art, structure, and narrative. Like in Hagood’s book, How to Sit contains within its pages space for the reader to reflect, catch a breath, and think.

If Coleman’s page space reminds us to think about divisions, Vivian Gornick’s Fierce Attachments begs readers to think about time. In her memoir, page space, about the length of a short paragraph, separates the past from the present. She writes about her childhood, growing up in her Jewish neighborhood in the Bronx, but she also intersperses her present relationship with her mother by writing of their ambling walks through Manhattan. These wide gaps serve to remind us that we are moving across time; the page space works like a crosswalk across a busy street. However, she breaks this pattern in the pages where she’s tells about her complicated affair with a married man—that page space is smaller. And so here, we are rushed, we can see that in this relationship, she is constrained. There isn’t as much space to breathe. The use of page space, and the changes in the amount of page space she uses, add to the understanding of her life and call attention to the moments that impact her.

Page space in Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House has the effect of evoking weight, like Kinkaid’s “Girl” but also of contemplation, as in Ways of Looking at a Woman. In fact, I also think it is fair to say that the use of the page forces readers to think about violence in ways similar to how Coleman asks readers to think about race and family. And, like Gornick, Machado’s book uses the page to mark shifts in time and events. In In the Dream House, the paragraphs are squares of text, and as Machado builds the story about her past abusive relationship, each page becomes like a brick of their house. Page space, here, works as a way to be heard—a way to yell without appearing too loud. In her chapter “Dream House as Epiphany,” Machado writes only, “Most types of domestic abuse are completely legal” (Machado 112). In its simplicity, in its starkness against the page, she is calling attention to the truth of violence, and begs us to feel how heavy a sentence can be. And we do, we do.

And so, if page space reflects the multitudes of thoughts women writers stream, then the page space in Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts is a prime example of shifts in space and thinking. There is almost no consistency in the amount of space between her paragraphs—she sporadically fluctuates between allowing one space and two between thoughts. I marked them, trying to seek out a pattern, and gave up, realizing that this intermittent use of space in a queer memoir about theory, gender, motherhood, and art would never be confined to a pattern or organization in its transitions. However, in addition to using page space between her paragraphs, Nelson fills the space most authors don’t use. There are footnotes in the left margins. In this, the space around her words becomes a place for her to cite her sources. That she cites them in the very place where her readers might also be writing makes her footnotes feel more like camaraderie.

Since page space can be used to mimic women’s speech, or their tendency to consider how much space they take up in the world, Esme Weijun Wang’s The Collected Schizophrenias becomes a way to study the silence and space of female disability. Her memoir uses page space to reflect the ways women and their pain, specifically though not solely psychiatric symptoms, are mocked, unheard, dismissed. Though there are gaps in her narrative, they are thin lines of space between paragraphs, not large enough to draw attention to themselves. The structure of her pages are, for the most part, “traditional.”

However, she does use less traditional forms to convey her stories. Wang inserts letters, emails, diagnosis codes, and excerpts from the DSM within her personal accounts, and these empirical resources serve to “back her up.” In a book about schizophrenic disorders, where a fractured narrative filled with page space might underpin her own experience, her tightly rendered prose becomes a way to avoid being dismissed. If there were gaps on her pages, might they, too, be misread, misunderstood, or seen as a problem, much in the way she is seen in real life? Because in truth, Wang has to hold it together to be heard; she has to take up more space, stay more or less linear, solid, because the space she takes up is already one that is shunned.

Women writing creative nonfiction use structure as a way to portray fragmented relationships, gaps in understanding, or shifts in thought. As a way to reflect the way we talk to, and listen to, each other. And on a larger scale, perhaps, this a way for female nonfiction writers to take up space or not, because we are taught from a young age to be aware of our presence in public. But as I sit here, surrounded by books written by women who use page space in their memoirs, I see its use as a way to unify fragments, because fragments are the way I think. As I type this I nervously glance at the clock. Is it time to pick my son up from school? Is that a student email in my inbox? Have I forgotten to bring the dog back in? I crave a silent space to think.

Jane Alison, in her book, Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative, analyzes the many different shapes of narrative. When she writes of “networks and cells,” she considers how chronology is affected in works that are segmented. Like Root, she notices that in segmented forms, “…no linear chronology makes the parts cohere; instead, you draw the lines” (190). Perhaps this is precisely what I’m searching for in this consideration of the shapes and space of the and on the page. Because it seems that bricks of text would plod, but they don’t. Earlier, in looking at Kinkaid’s “Girl,” I was concerned with how the solidity of the form represented and reflected the point of the essay, what type of space the essay took up. But if I ask myself, how does Kinkaid’s piece move? I have to admit that it does and it doesn’t. And that’s precisely the point. Her essay is not segmented, but one segment. The piece is the whole. And yet, these directions move us through the daily tasks. In the stuck-ness, we get through the day.

But what about longer essays, full-length memoirs? How does a story move when the narrative is fragmented?

II. Movement within page space/ page space as stillness

The book Waveform is an anthology of essays written by women over the past twenty years. Early in, Jericho Parm’s essay “On Puddling” appears, written in twenty-two numbered sections, which makes sense, because in her essay she also writes about lists, categorization, and organization. But this essay is and isn’t a list, because though there is a sequence of numbers, the paragraphs don’t follow a linear order. They follow a train of thought. Though writers are often taught that stories (both fiction and non) should follow an arc—a rise up to a critical choice, a decision, then a resolution—there are so many other ways to build narrative, to write movement. For Parm’s essay, the movement is in the page space. A list essay is fragmented, and so page space is inevitable, a thin line of blankness before counting out what’s next. Movement emerges from the reader’s desire and success of following the meandering narrative, and so it is in these gaps where the reader is forced to think, however briefly, about where Parm’s thoughts will wander to next.

This is not to say that her fragmented essay has no threads. The link between these sections, which speak of the death of a college friend, loss, doubt, and seeking, are linked by butterflies, Nabokov’s and her own, as well as her deceased college friend’s, and the meandering way of her thoughts follows the flight path of a butterfly. I can’t help but think back to Alison and Meander, Spiral, Explode, how she writes of W. G. Sebald’s seminal work The Emigrants, which I read in grad school when I was trying to find my place in the world, and in which Sebald also reflects on Nabokov and his butterflies, and how, in The Emigrants, which is also fragmented, which is why it works so well for Alison’s analysis of narrative shapes, Sebald, unlike the women authors I am looking at, fills the gaps in his narrative instead of leaving them. His page space is instead devoted to photographs. He takes up all the space.

Sebald’s is not the only fractured form Alison analyzes in this chapter about cells and networks. She also considers works like Susan Minot’s essay “Lust” in a way similar to my consideration of “On Puddling.” In her analysis of Minot’s crots, which explain and explore the variety of sexual partners and experiences she’s had, Alison notes the movement that occurs from crot to crot: “A reader dwells in one moment, then hops over white space to the next, with no sequentiality” while also writing that “‘Lust’ looks like a series of windows or cells, each one revealing something fairly static. But movement comes when I ponder each, scan the whole, and draw my own lines from cell to cell until they subtly reveal so much more” (Alison 195). But I believe that the space between these words is where such a pondering is allowed to happen. This is where the narrative moves. And so, in these essays, in longer works like In the Dream House, the page space works like a path, from this brick to the next, until the story is complete. Perhaps, if we understand paragraphs as a way to organize ideas, a way to make order out of chaos, then we should see page space as the flow of narrative movement.

III. Two faces and a vase

Alison also writes, “The questions a spatial narrative asks are not ‘what happens next?’ but ‘why did this happen?’ and, more complexly, ‘what grows in my mind as I read?,’” When she says “spatial narrative” she means these narratives filled with page space; when she asks what emerges in her mind as she reads, she means “how do these parts equal a whole?” And as she notes the way crots or segmented essays and books become unified, I understand the page space that is left behind functions as movement but also as a space to sort out what a writer is putting together. In fact, the page space feels like conversation. I understand what she is saying, her questions of why and what, and as I ponder her claim, I want to add, another question: How? How does this work?

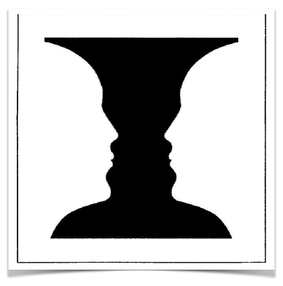

As a child, I enjoyed optical illusions. MC Escher’s drawings, a sketch that looks like both an old woman and a young one, impossible cubes that look like they are both coming and going, and this one, which, if one were looking at the white parts of the image, is seen as two faces, but if the focus is on the background, the image is of a vase:

For so long, I only saw the faces, maybe as a result pareidolia, the human tendency to see human characteristics on non-human things. But once I saw the vase, I could not unsee it, in fact, I almost saw the drawing as a moving picture, my eyes shifting focus to try and see both things at the same time. Perhaps we can try to read these narratives in a similar way, maybe we can see how the two parts work to form one thing. Though we should, in these fractured narratives, read the shape of the words like Alison does, we must also look at what those background shapes do to our perception of the whole. And that whole, when taken together, adds a new dimension to understanding the text.

When Alison questioned why and what, and I responded, in my head, how? it felt, for a moment, like we were having a conversation. It seems like she is analyzing the two faces and I the vase. In Alison’s epilogue, Aristotle’s hylomorphism: “Shape ordering life.” The space of the words and the blank space around it make up the shape.

“In the end, it’s not the classification itself that’s important. The more interesting conversation is what it’s doing—and how it’s doing it,” Karen Babine writes in her LitHub essay, “A Taxonomy of Nonfiction; Or the Pleasures of Precision.” That “how” can sometimes be answered by looking at the page and reading the page space. Remember Kinkaid? It doesn’t matter if it is a poem or an essay or a story, what’s important is the way the writing feels, the way a reader is given no space for thinking, only for reaction. Kinkaid’s words are shaped to make to her reader understand what it means to be a woman in the West Indies: Closed. In.

When Alison questioned why and what, and I responded, in my head, how? it felt, for a moment, like we were having a conversation. It seems like she is analyzing the two faces and I the vase. In Alison’s epilogue, Aristotle’s hylomorphism: “Shape ordering life.” The space of the words and the blank space around it make up the shape.

“In the end, it’s not the classification itself that’s important. The more interesting conversation is what it’s doing—and how it’s doing it,” Karen Babine writes in her LitHub essay, “A Taxonomy of Nonfiction; Or the Pleasures of Precision.” That “how” can sometimes be answered by looking at the page and reading the page space. Remember Kinkaid? It doesn’t matter if it is a poem or an essay or a story, what’s important is the way the writing feels, the way a reader is given no space for thinking, only for reaction. Kinkaid’s words are shaped to make to her reader understand what it means to be a woman in the West Indies: Closed. In.

IV. How else does page space function? Space as tension.

In 1977, Julia Kristeva published her essay “Stabat Mater.” I love Kristeva’s piece because it is two essays, connected but also distant. It is an academic analysis of the cult of the virgin, the decline in practicing Catholics, the role of women as mother, daughter, virgin. And yet, those words run alongside another essay, an essay that sings the struggles and beauties of motherhood, her motherhood, after the birth of her child. The essays are written in side-by-side columns, separated by the thinnest gap of page space. And I read this break as tension, a juxtaposition of motherhood and academia, of lyricism and analysis, of self and research. I wonder if she is telling me the two can never merge, that there will be a tension, always, between these two types of writing.

The tension comes in the closeness of the two essays, that thin line of space feels like the air between two magnets, or the moment before a rollercoaster dips, a breath held. After reading Jericho Parm’s essay in Waveform, I read Dana Tommasino’s “birdbreath, twin, synonym.” In this essay, Tommasino’s writes with lyric poeticism about her relationship with her brother and his relationship to addiction. She plays with language so that sentences look like erasure poems; the piece is told in fragments. Between sections, the page space is marked with a horizontal line, which makes me take a longer pause, much like Coleman’s How to Sit, where lines seem to be placed as a dare: Will you cross this boundary to find out what’s next? And just as I start to get a feel for the way the space, with its thin line, is adding tension, Tommasino does something new, yet familiar.

In the fifth segment, she writes:

In 1977, Julia Kristeva published her essay “Stabat Mater.” I love Kristeva’s piece because it is two essays, connected but also distant. It is an academic analysis of the cult of the virgin, the decline in practicing Catholics, the role of women as mother, daughter, virgin. And yet, those words run alongside another essay, an essay that sings the struggles and beauties of motherhood, her motherhood, after the birth of her child. The essays are written in side-by-side columns, separated by the thinnest gap of page space. And I read this break as tension, a juxtaposition of motherhood and academia, of lyricism and analysis, of self and research. I wonder if she is telling me the two can never merge, that there will be a tension, always, between these two types of writing.

The tension comes in the closeness of the two essays, that thin line of space feels like the air between two magnets, or the moment before a rollercoaster dips, a breath held. After reading Jericho Parm’s essay in Waveform, I read Dana Tommasino’s “birdbreath, twin, synonym.” In this essay, Tommasino’s writes with lyric poeticism about her relationship with her brother and his relationship to addiction. She plays with language so that sentences look like erasure poems; the piece is told in fragments. Between sections, the page space is marked with a horizontal line, which makes me take a longer pause, much like Coleman’s How to Sit, where lines seem to be placed as a dare: Will you cross this boundary to find out what’s next? And just as I start to get a feel for the way the space, with its thin line, is adding tension, Tommasino does something new, yet familiar.

In the fifth segment, she writes:

After years disappeared, Shay at forty spots me at the courthouse, says, “Look at you, you’re beautiful,” his hurt teeth, his bloated face, his disbelief. Protective Services is taking his three-year-old. I’m there with my girlfriend, at Shay’s plea to us, to try to adopt this Jackson we don’t know. But it won’t work. We live too far away. And birth

parents have visiting rights no matter how negligent.

undone churches, breast breezes, the drift abundantly.

By this point in the essay, the reader is no longer unsettled by the italicized word salads Tommasino peppers in; they make sense as part of her understanding sadness, part of her finding the right words to describe love and loss. But to drop the line like this is to disrupt the hypnotism of the scene, of the language. It is a depiction of ruined relationships, and perhaps fractured government systems. The page space interrupts the narrative, jars the reader, ups the tension, breaks the heart.

Part Three: Conclusions

After reading quite literally through these memoirs and essays to see what impact page space has on narratives, it seems as though much can be read into the appearance of the page. There is a way these narratives move, asking readers to take note of pauses and gaps, of language as it appears.

We lost a tree in a recent storm; a century-old walnut that once held up the south end of our hammock. It landed on our kitchen roof, hard enough to shake the adhesive from the shingles, but at an angle that avoided hitting the potted plants below. A lemon tree, a fragile eucalyptus, a bushy gardenia with easily bruised petals, all safe beneath. Now that the felled tree has been cut off the house, sawed into chunks and hauled away, there is a gap in our yard. I leaned my head out the kitchen window today, having momentarily forgotten. And then I saw, in that space where a tree used to be, my neighbor’s skinny black pine and creeping rose garden, a faraway stone wall, and a nest that must belong to the night heron I’ve seen overhead every evening. A whole story in the space behind what I once knew to be true.

Though there is no one way to read the gaps, no one way to describe what happens when a writer drops a line, writes in the margins, but that the space exists at all is something that should be pondered, a part of the whole that allows for both reader and writer and to feel the art of the story.

We lost a tree in a recent storm; a century-old walnut that once held up the south end of our hammock. It landed on our kitchen roof, hard enough to shake the adhesive from the shingles, but at an angle that avoided hitting the potted plants below. A lemon tree, a fragile eucalyptus, a bushy gardenia with easily bruised petals, all safe beneath. Now that the felled tree has been cut off the house, sawed into chunks and hauled away, there is a gap in our yard. I leaned my head out the kitchen window today, having momentarily forgotten. And then I saw, in that space where a tree used to be, my neighbor’s skinny black pine and creeping rose garden, a faraway stone wall, and a nest that must belong to the night heron I’ve seen overhead every evening. A whole story in the space behind what I once knew to be true.

Though there is no one way to read the gaps, no one way to describe what happens when a writer drops a line, writes in the margins, but that the space exists at all is something that should be pondered, a part of the whole that allows for both reader and writer and to feel the art of the story.

Related Works

|

Victoria Brown

How We Write When We Write About Life: Caribbean Nonfiction Resisting the Voyeur Assay 6.2 (Spring 2020) |