ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

10.2

10.2

|

My difficulty is that I am writing to a rhythm and not to a plot.

—Virginia Woolf, letter to Ethel Smyth, 28 August 1930 1.

In eleventh grade I discovered that difficulty can give pleasure and that the simple can be a cheat. All at once, my world flamed up. Until that school year, Mrs. Troup, kindly, blue-eyed, and middle-aged, guided my English education at the Moravian Seminary for Girls. She favored Ogden Nash for creativity, and for backbone had us diagram sentences to reveal the skeleton of grammar. In her classes on the second floor of Main, with its sharply slanted ceilings, we damned the unsolvable and grappled only with the plotted. Mrs. Troup’s approach discontented me, though I couldn’t name my dissatisfaction or my yearning. I felt that the body flesh of writing had escaped me. Then Mark Hinderlie, a recent graduate of Yale, came to teach. He lit firecrackers in the classroom. For the first three weeks of class we had to write a new short story every school night. What? we yelped. Write? We’re not writers. We had written nothing but five-paragraph essays. Nonetheless, preposterous as the task was, my classmates and I each wrote fifteen stories in three weeks. The demand—the format of the short story confronted again and again, the repetition of those nights in my room—produced effusions nothing like the formulas Mrs. Troup had espoused. Characters emerged, images and emotions. Where do these words come from? I asked. This daily outpouring is one of the mysteries of my life. In the midst of it I learned that, to some small measure, I shared a creative spark with the writers we studied in class. Each day we read our work to each other and Mr. Hinderlie treated us as writers—a revolution in self-concept. Most of our stories were rubbish, but not all. At the time, I didn’t grasp the pedagogical theory behind our writing boot camp. Much later I saw that Mr. Hinderlie wanted to push us from one role, passive readers of literature, to another, creative makers—makers, even, of texts written by someone else. In my writing I have more than once revisited this spot of time, in which I became a writer. One instance is an essay in my collection Studio of the Voice, “Inflammatory Questions.” It was inspired by Jenny Holzer’s Inflammatory Essays, which I encountered at the Broad Museum in LA. Her work consists of monumental columns of colorful posters filled with brief texts that Holzer herself has written. The same words recur at different positions in the columns, with a dazzling effect that relies on the principle of repetition. In my own effort to inflame, I substituted questions for Holzer’s mini-essays, a mode that captured uncertainty about my voice as a writer, my struggles to understand myself, my origins, my own composition—questions that can never be resolved. They can only be asked again. The questions are also laid out in columns and recur. And so the repeated questions inspired by Holzer unearthed something of the truth of my life as a writer. One of the cells in my essay asks the questions I cannot answer: Was it in Mr. Hinderlie’s class your junior year in high school, when you had to compose a story from scratch every night for three weeks, that you began to think of yourself as a writer? It felt like riding your horse without a saddle, your skin next to his. Why were you surprised by the full-throated ease of what came out of you? Will you ever understand the voice that carried you to the place you didn’t know you had inside you? “Inflammatory Questions” comes to no conclusions. It signals a belief that we are mysterious to ourselves and to each other. It revisits scenes of doubt, minus the apparatus of a narrative with linear progress—Mrs. Troup’s plot. Its craft (its power, I hope) is incantatory, not expository. That is to say, using Woolf’s words, I wrote to a rhythm, a time signature. The more my words repeat and build, the more my voice is realized. I am compelled to confront these mysteries in my writing, not to dissolve them. 2.

Modern and contemporary poems, plus Faulkner, were the published texts Mr. Hinderlie had us read the autumn my world changed. He introduced us to literature usually characterized as difficult. I’m not talking about negotiating obscure words, an unfamiliar dialect, or allusions to dark events, elements that can indeed make a text less accessible. I’m talking instead about literature that doesn’t rely on arcs of progress, on package delivery. In some of the works we read, forward progress is contraindicated: Faulkner’s novel as chamber music, As I Lay Dying, for example, spins round and round in Addie’s head. Our teacher would bring in a poem and ask us to spend the period writing about it. I think now that we were being introduced to close reading. How alive I felt encountering these unknown poems, impenetrable maybe, but somehow nutritious. Unlike some of my classmates, who felt shut out from texture and meaning, I felt invited to dine. I was active in creating the poem’s meaning, which resisted summary in a neat thesis statement. It was something that might change each time I addressed the text. Wallace Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” is another example of our reading, a poem familiar now but then new to me. Much has been said about it, but I want to notice what it opened up for me. The thirteen ways are brief, numbered sections. Stevens called them “sensations,” bits of sensory experience. These fragments or facets present different perspectives, with the bird offering disparate images as the poem proceeds. It stops at thirteen ways of looking, but there might have been thirty or three hundred. It could go on forever. What unifies such a poem? It does not present an arching narrative or make an argument about blackbirds. If there is a strategy of unification, it involves the sensations evoked, and those feelings are distinct for each reader. The blackbird poem was one my first experiences of literature based not on narrative but on lyric impulse. It has ever since informed my experimentation in lyric structures for essays. As a student, I was steeped in modernist aesthetics: the stream of consciousness of Virginia Woolf, the long quoting poems of Marianne Moore, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, the competing voices and perspectives of William Faulkner. Much of what I absorbed expresses itself in the shape of my essays. Eschewing chronology and formula, breaking up expectations of narrative continuity, creates a different rhythm, drawing attention to the process and materials of creation and redirecting the authorial role toward the reader. Through selection and arrangement, I invite the reader to put the pieces together, to feel the “sensations.” My embrace of alphabetical forms, for example, comes from a study of modernism that began way back then. I have employed the alphabet in large-scale works, such as Companion to an Untold Story, and, in Studio of the Voice, “Bride of Cows,” an essay whose story, in Vivian Gornick’s sense of the word, was the recent death of my mother. I find myself in Virginia at a writer’s retreat, awarded many months before, and the essay wanders, or I should say reels, about the landscape in the aftermath of her sudden death. Being unsettled was perhaps the most profound sensation I felt writing “Bride of Cows.” The alphabetical form, with its repeated jump-cut to the next letter, captures the dislocation visited upon me, how grief unbalanced me. The alphabet creates relationships between the entries, much like Stevens’ numbers, and these juxtapositions complicate rather than flatten the material. The alphabet imposes an order but invites randomness: an order that undoes order. Alphabets don’t allow us to settle. Each entry adds to the whole while qualifying what came before, much the way the identical cell in “Inflammatory Questions” changes with each repetition and alteration of the order. Finally, the alphabetical form provides the necessary distance from the material that allows me to see it anew and reorchestrate it for the reader. 3.

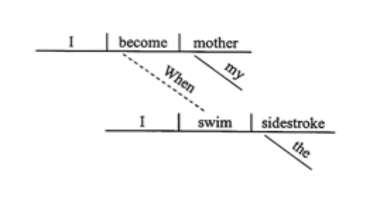

I asked my students to compose a one-sentence memoir and to write it on the blackboard. Following my usual practice, I did the same. In the lower right corner of the board, which now held twenty-five personal histories, I inserted, When I swim the sidestroke, I become my mother. Out of that sentence came my essay “Sidestroke,” which diagrams my haunting relationship with my mother (please remember that the title of this piece is “On Difficulty”). Mrs. Troup would have pointed out that it is a complex sentence (you bet it is!), a sentence composed of a main clause and a subordinate clause. An independent clause can stand by itself: I become my mother. Clauses that can’t stand on their own are dependent or subordinate. When I swim the sidestroke depends upon I become my mother to complete it. Even when the subordinate clause comes first, it is diagrammed below the main clause, a visual graph of emotional hierarchy and anatomy. Grammar mirrors psychology. Is it a poem, a story, an epic, a tragedy in two acts, a comedy? It asks the most difficult of questions—what does it mean to say I become my mother? It is a sentence like an iceberg with seven-eighths of it underwater. Helen Jane Keller Troup retired from Moravian two years after I graduated, and died in 2006. Let me in her honor refer to the mother clause and the daughter clause, which depends upon the mother to complete it.

|

|

Marcia Aldrich is the author of the free memoir Girl Rearing, published by W.W. Norton, and of Companion to an Untold Story, which won the AWP Award in Creative Nonfiction. She is the editor of Waveform: Twenty-First-Century Essays by Women, published by the University of Georgia Press. Her chapbook EDGE was published by New Michigan Press. Studio of the Voice from Wandering Aengus Press was released in 2024. Her website: marciaaldrich.com. Her essays have been included in The Best American Essays.

|