ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

3.2

3.2

|

Allow me to take you back in time a bit, back to Massachusetts in the 1830s. Picture endless forests teaming with wild hare and muskrat, rivers and lakes bubbling with pickerel and minnow, the sky aflutter with robin and hawk, hearty soil waiting for the bright blade of a New England farmer’s plow. What is the government of a fledgling democracy to do when faced with such abundance? Take inventory, of course.

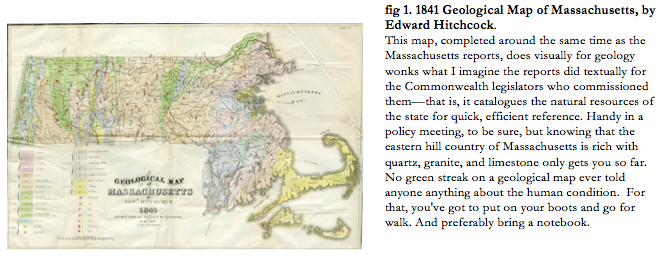

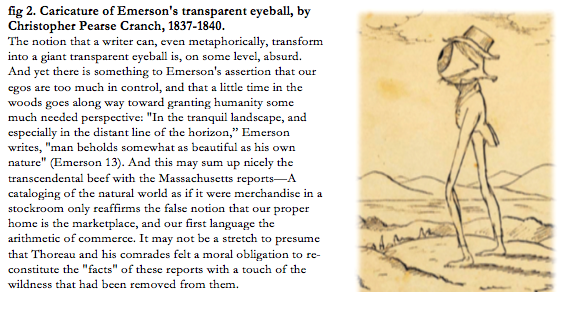

In the early 1830s, The Massachusetts legislature commissioned four reports on the natural history of their state that would "promote the agricultural benefit of the commonwealth," and highlight "that which is practically useful . . . to persons whose honorable employment is the cultivation of the soil" (Report VI). The results were four book-length reports: Fishes, Reptiles, and Birds of Massachusetts (1839), Herbaceous Plants and Quadrupeds of Massachusetts (1840); Insects of Massachusetts (1841); and Invertebrata of Massachusetts (1841). Taken together, these reports constitute more than one thousand three hundred pages of facts and figures, data to marshal and catalogue the whole of the wild commonwealth, charts and indices to itemize and account for all the creeping things. There is an Old-Testament inclusiveness to it, an accounting that would have made Noah or Adam proud. And while the word "Invertabrata" is enough alone to warrant the recollection of these reports, remember that this was Massachusetts in the mid-19th century, ground zero for American Transcendentalism. Such an unabashedly pragmatic, government-sanctioned demystification of the wilderness would have been enough to bring tears to Emerson's giant transparent eyeball, and the Transcendentalist reaction to these reports can be instructive to those of us interested in the value of facts in creative nonfiction.

Enter Margaret Fuller, editor of The Dial, a fledgling literary magazine founded as a showcase for transcendentalist ideals. Imagine fuller and the rest of The Dial’s editorial board gathered in a smoky conference room to vent about the government’s shameless attempt to reduce the wilderness to a warehouse inventory. 'What do we do with all this?' Someone might have said, holding up the stack of reports. And Fuller might have said, "Who knows? Let's give them to Thoreau and see what he comes up with."

In the July 1842 edition of The Dial, Fuller writes: "We were thinking how we might best celebrate the good deed which the State of Massachusetts has done in procuring the Scientific Survey of the Commonwealth" ("Preliminary Note," 19). And perhaps I'm merely projecting, but I can hear in her voice a bit of understated exasperation, or perhaps a transcendental longing for someone to deconstruct the Commonwealth's "good deed" into something more organic that might actually capture some of the beauty and grandeur of Massachusetts. Certainly what she goes on to write backs up this conjecture:

We found a near neighbor and friend of ours, dear also to the Muses, a native and an inhabitant of the town of Concord, who readily undertook to give us such comments as he had made on these books, and better still, notes of his own conversation with nature in the woods and waters of this town. (19) However it happened, Thoreau was tapped to make some transcendental sense of the heaping pile of reports—Fuller called him a “neighbor and friend . . . dear also to the Muses,” and it would be his charge to engage the facts in those reports and revision them into art.

In the resulting essay, “The Natural History of Massachusetts,” Thoreau seasons information from those reports with personal observations, anecdotes, and meditations, adding literary weight to an otherwise impenetrable mass of facts. Thoreau’s essay is a natural history of a quality well beyond the scope of bottom-line-minded legislators. It is a natural history written for those who love the Commonwealth’s resources not for their market value, but for their spiritual, psychological, and emotional value.

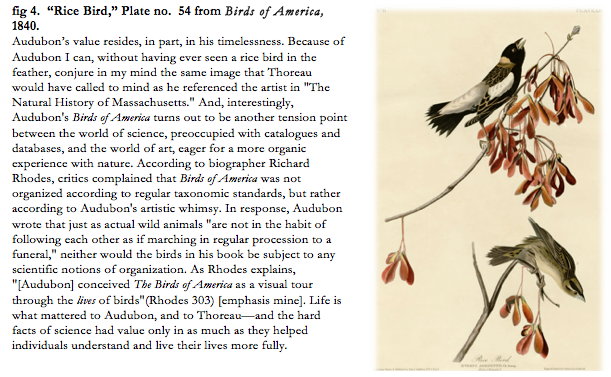

Thoreau doesn’t begin by addressing the reports themselves head on, but he works his way toward them. “Books of natural history make the most cheerful winter reading,” he writes. “I read in Audubon with a thrill of delight, when the snow covers the ground, of the magnolia, and the Florida keys, and their warm sea breezes; of the fence-rail, and the cotton-tree, and the migrations of the rice-bird; of the breaking up of winter in Labrador, and the melting of the snow on the forks of the Missouri" (19). Thoreau describes such writing as “reminiscences of luxuriant nature,” and contrasts the lively writing of Audubon and other nature writers to the dry, government reports that “deal much in measurements and minute descriptions, not interesting to the general reader, with only here and there a colored sentence to allure him, like those plants growing in dark forests, which bear only leaves without blossoms” (39). To Thoreau these reports are, at best, sickly saplings starving for sunlight, all wood and no bud. And yet, he sees in these volumes of raw data, not a waste of time, but an opportunity. “Let us not underrate the value of a fact,” he writes. “It will one day flower in a truth” (39). Thoreau knows that the truths we discover in writing blossom from our engagement with facts, from reflection on experience and observation: “Nature will bear the closest inspection,” he tells us. “She invites us to lay our eye level with the smallest leaf, and take an insect view of its plain . . . every part is full of life” (22). And in his meandering essay he proves his point one animal, one leaf, one shell at a time. Throughout “The Natural History of Massachusetts,” Thoreau treats the bland facts of those legislative reports as catalysts for anecdotes and meditations that lead to the discovery of a truth that really matters—a deeper understanding of our place in the natural world. A close reading of this essay serves as a master class in how writers can help facts blossom into truths.

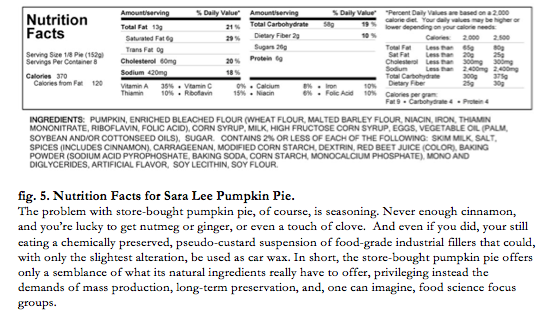

Any writer who has stared at volumes of research or boxes of archival data know the challenge of processing hard facts into something worth reading. Thirteen hundred pages of diagrams and charts and catalogues would no more help a reader discover the natural world of Massachusetts than, say, a nutrition facts label would help a diner appreciate the subtle flavors in a slice of good pumpkin pie. Thoreau references the data, but then invites us into the woods for a glimpse of what that data translates to in the actual wilderness. In a passage about birds, Thoreau begins: “About two hundred and eighty birds either reside permanently in the State, or spend the summer only, or make us a passing visit.” But then he proceeds to animate those two hundred eighty birds for the reader:

Those which spend the winter with us have obtained our warmest sympathy. The nuthatch and chickadee flitting in company through the dells of the wood, the one harshly scolding at the intruder, the other with a faint lisping note enticing him on, the jay screaming in the orchard, the crow cawing in unison with the storm, the partridge, like a russet link extended over from autumn to spring, preserving unbroken the chain of summers, the hawk with warrior-like firmness abiding the blasts of winter, the robin. (23) Thoreau allows us a kinship with the birds, and tracks the seasons by tracking their movements through Concord: Nuthatch and Chickadee in winter, Duck and Fishhawk in spring, Flicker and Phoebe in summer, and Oriole and Goldfinch in autumn. The birds listed by the report become, in Thoreau’s essay, Father Time’s feathered fleet, marking the cycle of the seasons. And the subtle anthropomorphism he applies to each bird lifts them off the page, builds a nest for them in our hearts and minds, and invites them in to roost.

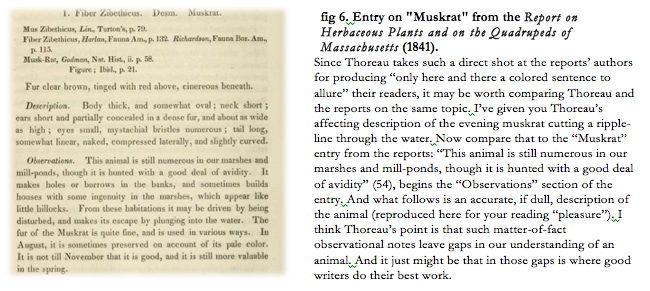

Thoreau does something similar in a passage about quadrupeds. First he gives a nod to the government data: “It appears from the Report that there are about forty quadrupeds belonging to the State,” but he immediately ushers us back outside again, recalling for readers the annual flooding that occurs in the spring and how “the wind from the meadows is laden with a strong scent of musk, and by its freshness advertises me of an unexplored wildness” (28). And now that we are in the musky-scented wilderness, Thoreau offers us another wild image to consider: “Frequently, in the morning or evening, a long ripple is seen in the still water, where a musk-rat is crossing the stream, with only its nose above the surface, and sometimes a green bough in its mouth to build its house with” (29). He describes the industry of the muskrat, how it ‘survey[s] its neighborhood’ at any sign of danger, how it ‘erect[s] cabins of mud and grass,” to be used as “hunting lodges” (29), and as with his comments on the migratory habits of birds, Thoreau uses the details born of his own observations to recreate for the reader a sense of the vibrant ecology of the muskrat. The author’s personal experience blends with the facts of the reports and in so doing humanizes an otherwise unremarkable rodent. Throughout the essay, Thoreau brings the animal kingdom under close scrutiny and reveals their many seemingly human habits and traits, and in so doing invites readers to broaden their perceptions of the animal kingdom—an invitation the legislative reports are constitutionally incapable of making. But perhaps the most telling observation in Thoreau’s essay comes when he lays human beings under that same close scrutiny. In a passage about the various fishes found in the rivers and streams of Massachusetts, Thoreau paraphrases from the reports: “Of fishes, seventy-five genera and one hundred and seven species are described in the Report” (30), but then he paddles us out in a boat on the Concord River to relive a memory with him:

I stay my boat in mid current, and look down in the sunny water to see the civil meshes of [the fishermen’s] nets, and wonder how the blustering people of the town could have done this elvish work. The twine looks like a new river weed, and is to the river as a beautiful memento of man’s presence in nature, discovered as silently and delicately as a foot-print in the sand. (31) Whereas the Massachusetts reports by their catalogue structure of lists and subdivisions draw a harsh distinction between a human curator and the natural world he oversees, Thoreau’s essay challenges us to break down those artificial barriers between man and nature. He revisions man not as a mere observer or accountant of the natural world, and not as an intruder in some foreign wilderness, but as an essential element of that world. He renders civilized man as wild as the fishes themselves, their fishing line as natural as river weed, “no more an intrusion than the cobweb in the sun” (31).

In “The Natural History of Massachusetts,” Thoreau takes the government’s effort to catalogue the world and transforms it into an opportunity to reconsider man’s place in that world. This is the hard work of the observant writer—to take information and filter it through personal experience and observation, to cultivate a fact into a truth. And this is why writers engage with the facts of the archive, the detritus of the database. Alexander Smith writes “the world is everywhere whispering essays” (Smith), and I believe this is true, but, as Thoreau demonstrates, sometimes those whispers are muffled inside the thick, dense binding of a thirteen-hundred page, four-volume set of natural history reports. Sometimes the world whispers from the deep corners of our ancestry, from the dusty archives of newspapers, or from the raw elements of an interview.

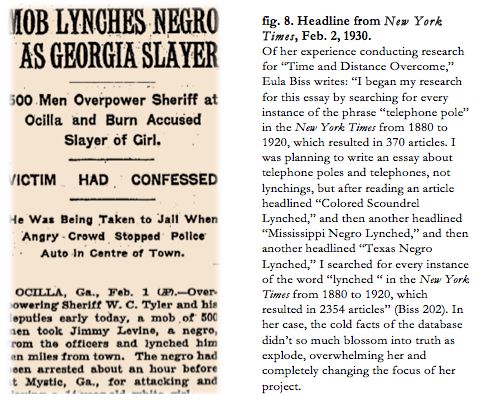

The research-minded nonfiction writer is the “near neighbor or friend,” who, like Thoreau, is “dear also to the muses”—someone capable of the labor required to refine the world of information into story, sifting through the raw materials of fact and uncovering a new world for themselves and the reader. So many of the essays that move me—where would they be without research? Elena Passarello’s “Hey Big Spender,” a quirky essay on the erotic history of castrates, Eula Biss’s marvelous, heartbreaking essay on lynching, “Time and Distance Overcome,” which started out as a New York Times archival search on telephones; Brian Doyle’s “Joyas Voladoras,” a lyric meditation on the heart; the meandering allusions to mythology, the Bible, art, and literature that humanizes Scott Russell Sanders’ alcoholic father in “Under the Influence;” the steady, intimate eye of Lia Purpura as she examines one corpse after another in “Autopsy Report;” Anne Fadiman’s “A Piece of Cotton,” in which she carefully reconsiders patriotism and flag etiquette in a post-9/11 world. These writers have all found their voice by getting beyond themselves and getting into the research. Consider a few fresh examples in greater detail: in the following passage from Hollywood’s Team: Grit, Glamour and the 1950s Los Angeles Rams, authors Jim Hock and Michael Downs combines information from several different sources, including the LA Times, Sports Illustrated, The Baltimore Sun, ProFootballArchives.com, and personal interviews to create a vivid description of the post-game atmosphere that attended the Cleveland Browns’ victory over the LA Rams in the NFL’s 1955 championship game (I’ve formatted the passage below to offer a visual indication of the work the writers have done to integrate their several sources. Colors change as sources change):

A cursory glance at this excerpt makes clear the work that has been done to abridge so many sources into a few paragraphs of text, but a close read suggests that the authors have not only summarized and paraphrased well; they have arranged the passage in an artful way suggestive of the vivid texture of fiction, helping the reader feel present on the night of the Brown’s victory. Consider the placement of raw data about payouts to players on the winning and losing team. This is the kind of wonky information a sports nut might find interesting, but what humanizes the selection is the choice to follow up that data with the quote from Bob Gain. The quip from Gain about the payout being enough to “buy a car… Not all new cars, but–like–a Chevy,” captures the players’ pleasure in getting paid to play football while underscoring the relatively small amount of money these players were making when compared to today’s multi-million-dollar expectations. The passage illuminates a bygone era in American Sports and offers an everyman impression of professional athletes. Readers feel more familiar with and more empathetic toward Gain and the other players precisely because the authors have given them voice in this particular way.

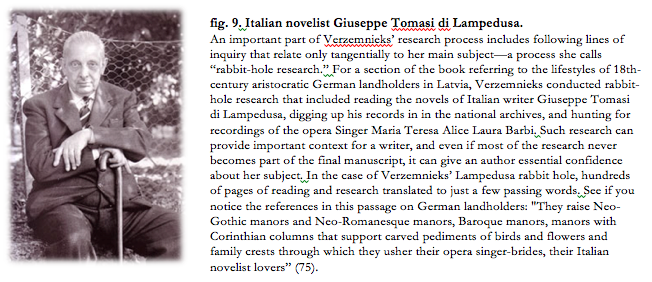

Inara Verzemnieks takes a similar approach in Among the Living and the Dead: A Tale of Exile and Homecoming on the War Roads of Europe, a forthcoming memoir that retraces the lives of Verzemnieks’ Latvian ancestors. Below is a passage in which she offers a short social history of Latvians: The land which they call home has always belonged to someone else. There is no concept of Latvians as a people, except in relation to what they can do for others. To be Latvian is to be a peasant. Put another way, to be born within Latvia’s borders prior to the 20th century is more than likely to be born a serf, bound under hereditary contract to provide a lifetime of labor to the wealthy friends of whatever empire happens to be ruling Latvia at the time. (Verzemnieks 75) Verzemnieks uses this short passage to contextualize the life of her own great-great grandfather who, in 1882, became “the first of his family to own the land where every ancestor before him has lived and worked and died” (75). And though no sources are hinted at in this passage, the density of information implies an ethos that only comes from rigorous research. Indeed, Verzemnieks herself describes this passage as, “the distillation of several books,” amounting to hundreds of pages of reading in order to produce this 87-word description. And by placing her family’s 19th-century real estate deal in a broader Latvian context, she elevates the significance of her grandfather’s land purchase to the level of a historical moment. And likewise, the intimate portrait of her family’s historical record renders the broader history of Latvia in a more personal, humanizing light.

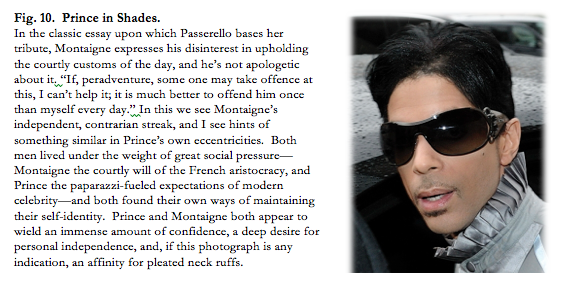

Artful distillations of research and information are an important hallmark of quality creative nonfiction, but it is often the liberties that authors take that give new life to that information. Consider Elena Passarello’s essay “The Ceremony of the Interview of Princes,” which was published in the anthology After Montaigne: Contemporary Essayists Cover the Essays. The anthology presents contemporary essayists riffing on Montaigne’s classic essays, and Passarello’s contribution is based on Montaigne’s short essay on the custom of excessive attention to courtly ritual among the European aristocracy. With Montaigne’s title as inspiration, Passarello writes a lyric commentary on the musician Prince, and the eccentric demands he made regarding media interviews. She began work on her essay by reviewing upwards of 100 different interviews and media appearances with Prince between 1980 to 2014, and then culling out every odd detail, quirky demand, and eccentric prohibition made by the pop icon in the course of those interviews (Passarello). And then, with her own trademark idiosyncrasy, Passarello mashed up that information into an imagined narrative documenting a hypothetical interview with Prince that takes place in the musician's private estate, Paisley Park. The essay, in part, reads as a laundry list of dos and don’ts:

Do not call him weird. This mock set of instructions is no realist’s labor to revisit some past event, but rather an artful attempt to create a mosaic of Prince’s eccentricities. And yet, as satisfying as it is to imagine that the wealthiest and most powerful among us are also the weirdest, in enumerating the oddities of celebrity behavior, the essay simultaneously reveals and critiques our own cultural preoccupations. If Prince is a screwball genius with a penchant for inconveniencing reporters, then we, the insatiably nosey viewing public, are at least partially to blame for that screwball genius. The application of research in this essay ultimately reveals as much about us as readers as it does about the celebrity it attempts to examine.

Ander Monson, an essayist with his own eccentric affinity for research, writes that because “we perceive the self through its contrast with the world . . . the world quickly must become an essential subject in any essay worth its salt” (Talbot 112). It is research that gives us access to the world, research that gives a jolt of verisimilitude to our stories, that deepens our meditations, foments personal discovery, complicates received notions, and helps keep us honest. I appreciate the famous Ron Carlson advice that a writer must keep his butt in the chair if he ever wants to get anything done; however, unless we occasionally get out of our chairs, and engage with the hard facts of the world, there’s no telling what we may miss out on.

Certainly had Thoreau stayed behind his desk, he could not have given us his lively, unconventional, heartening “Natural History of Massachusetts.” And perhaps if the Commonwealth legislature had not commissioned those soulless reports at all, Thoreau might have had one less reason to go floating with the muskrat. Writing feeds research as often as research feeds writing, and experienced practitioners of nonfiction know that splitting time between these two endeavors is essential. Near the end of “A Natural History of Massachusetts,” Thoreau draws a metaphorical comparison between the growth of crystalline frost and the way “vegetable juices swell gradually into the perfect leaf.” He sees a familiar structural complexity in hoar frost, in the plumage of birds, the architecture of coral, and ultimately in the complexity of art itself: “What in short is all art at length but a kind of vegetation or crystallization, the production of nature manured and quickened with mind?” (Thoreau 38). If one can forgive Thoreau his slightly scatological metaphor, I think the image is apt—experience and research puts writers in touch with "the production of nature," the world is "manured and quickened" in the mind of the writer. Cold dead facts blossom into truth, and the world that we must live in transforms into stories we cannot live without. |

Click here to download a printable PDF with Works Cited.

|

Joey Franklin's first book, My Wife Wants You to Know I'm Happily Married, won the 2015 Association of Mormon Letters book prize for nonfiction, and was a finalist for the 2016 Utah Book Award. His essays have appeared in Writer's Chronicle, Ninth Letter, The Normal School, Gettysburg Review, and many other publications. He teaches creative writing at Brigham Young University in Provo, UT, and is currently at work on a memoir about the saints and scoundrels hiding in his family tree. More information available at joeyfranklin.com.

|