ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

7.1

7.1

|

It might have been my third week in the Graduate Poetry course at the beginning of my MFA program. I mentioned that some line in someone’s poem could be more concrete. Joanna Straughn asked, “Concrete as in Concrete poetry?”

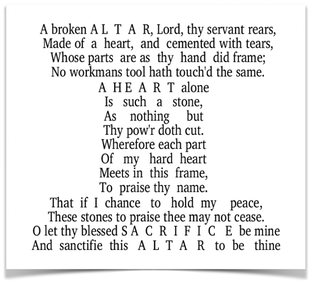

I wonder what my face looked like in response. Contorted, as if to say, “what is concrete poetry?” Or contorted as if to say, “Haven’t you heard that in poetry, you have two choices: concrete images or abstractions?” I’d been to creative writing classes my whole life. I worked on the high school literary magazine. I took creative writing at Reed even though at the time, the faculty turned genre every two years. I had Glen Scott Allen for two years, then Henri Cole for one. I don’t think they let me into the poetry course my freshman year but I knew concrete meant “salt” instead of “grief.” But I knew what she meant by capital “C” Concrete Poetry. I had been a big fan of May Swenson, who sometimes wrote poems in a particular shape. I kept her poetry close because she was a poet from Utah and I didn’t know until I read her bio that poets could come from Utah. I didn’t know how to read George Herbert yet but I did know when one of our classmates wrote a poem about death in the shape of a headstone, that sometimes when poems tried too hard to be what they wanted to be, they often fell apart. When Joanna said Concrete Poetry, she meant poetry about trees written in the shape of a tree. She meant, like Herbert’s altar poem, a poem about God and transcendence, church and actual altars. Concrete Poetry is very literal. It’s also very fast. How long should it take to reach God? If you do it perfectly, immediately. But, as Herbert would argue, humans are imperfect so it takes forever. Concrete Poetry is a kind of false immediacy. You think you get the meaning right off that bat. Poems in the shape of a heart. Oh, dear student, how many ways can I tell you the heart is a bloody, mass-y, veiny thing? If you’re going to write about love, it’s going to be messy.

__________

When I was a poetry editor at Quarterly West, the editors received two submissions in the mail. The first was a bag of bread crumbs. This was post 9-11 and we were a little concerned that someone we rejected was trying to kill us. We were more concerned about how, if we accepted the submission, could we reproduce the breadcrumbs faithfully.

That same season, we received a submission from Ander Monson. Having no official creative nonfiction or essay editorial team, the submission came to Julie Paegle and me, poetry editors. The piece had some lyricism. The piece had some story. In between the story and the lyrics were thousands of dots—ellipses that looked exactly like the poem’s title: “I Have Been Thinking About Snow” which begins I have been thinking about snow…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………….[186 dots approximately. I am a bad counter. Ander is precise] Consider the threat of mass extinction at the hands of one of the trillion comets and or midsize and up asteroids that we will not see until they hurtle right into us, raise a hundred square kilometers of the ocean, fog us over, kill us off…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ……………………..[191 dots approximately. I am a bad counter. Ander is precise.] Is snow a lack or a mass? The white suggests such lack. But what weight! I used to demand that my brother cover me over with snow until that I weighed so much that I could not move. Dots and text, dots and text until we get to page seven and eight where, in an ocean of dots, we have two words: “Such” on page seven and “Isolation” on page eight. The rest of the page is full of dots. But it means nothing here in my words if you can’t see it.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… But I shouldn’t let you see it out of context. The whole point is the act of reading the essay. It is unreproducible without the whole thing. The experience of reading it cannot be quickly summarized.

Near the end of the essay, the essay goes, My parents stopped taking me to church when I stole the merit badges from the Boy Scout trove kept in a closet by the kitchen……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………I felt that I deserved them for so many winters, so much weight borne under snow, so many skills demonstrated: fire-building, vandalism, plagiarism, compromise-brokering, dodging bottles and bottle-rockets, living through the oblong story of depression, weather and wilderness survival….. Weight and shapes. Oblong stories of depression, in Monson’s writing, words themselves aren’t enough to launch the reader toward meaning. In between the dots, we have emptiness and annihilation. Conversely, the dots give us snow and heft. To some people, snow may be light as can be, but in Monson’s essay, it accumulates.

__________

Concrete Poetry is the catapult meant to get us up and above earth. Meter makes concrete the way to negotiate the space between earth and heaven, human and God, syntax and punctuation, meter and rhyme serve dramatize, even imitate, what it takes to find God either up high in heaven or in the things of this world, in all the immanence. Imperfect rhyme highlights the human voice’s inability to reflect the supposedly perfect voice of God. Too-easy Concrete Poetry is an unearned, at least temporally, bid for transcendence. The significance of the poem is two-dimensional words invoking a third dimension. But without the fourth dimension, the graphic deflates, the launching pad loses bounce. Herbert makes his concrete poetry difficult with complicated syntax, his hendiadys, his meter slow but perhaps the essay has a greater capacity to dig deep into that fourth-dimension.

I think of Poetics as a way to gauge different kinds of concrete moves in a poem. My students and I, when reading a poem about Evil Knievel, note how the it leads the reader’s eye upward. Emily Viggiano Saland’s chapbook Trajecgtory begins with the piece Of the Items Necessary, Of course the wind. The reader’s eye moves from the horizon, to a birch tree, to the body, and then back out to the sky, following Evil Knievel’s signature flights and landings. Meter can be a capital C concrete as the lines make a running leap toward the edge of the page just as Marianne Moore’s Jerboa leaps. As the syllabics and alternating rhyme scheme suggest, the fashioning of an artifact should follow the habits and habitation of the represented object—as the Jerboa leaps a little unevenly, so should the rhyme scheme. As the Jerboa moves back and forth in the desert seeking his food, Moore’s syllabic imitation moves back and forth in a loose pattern. Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Windhover dives down from above to plow down into gold vermillion, taking his sprung rhythm down with him. Emily Dickinson stretches the arms of her dashes wide. If poetry’s aim is to enact or embody, for some poets, that includes the whole of the poem. Herbert’s space is the body/temple, endowed with windows for a mouth whose voice cannot escape the body but can only “in the ear, not conscience ring.” Herbert’s religious poetry, shaped as altars, temples, and windows, congregates every resource at Herbert’s disposal to catapult his imperfect self as perfectly as he can to a perfect God.

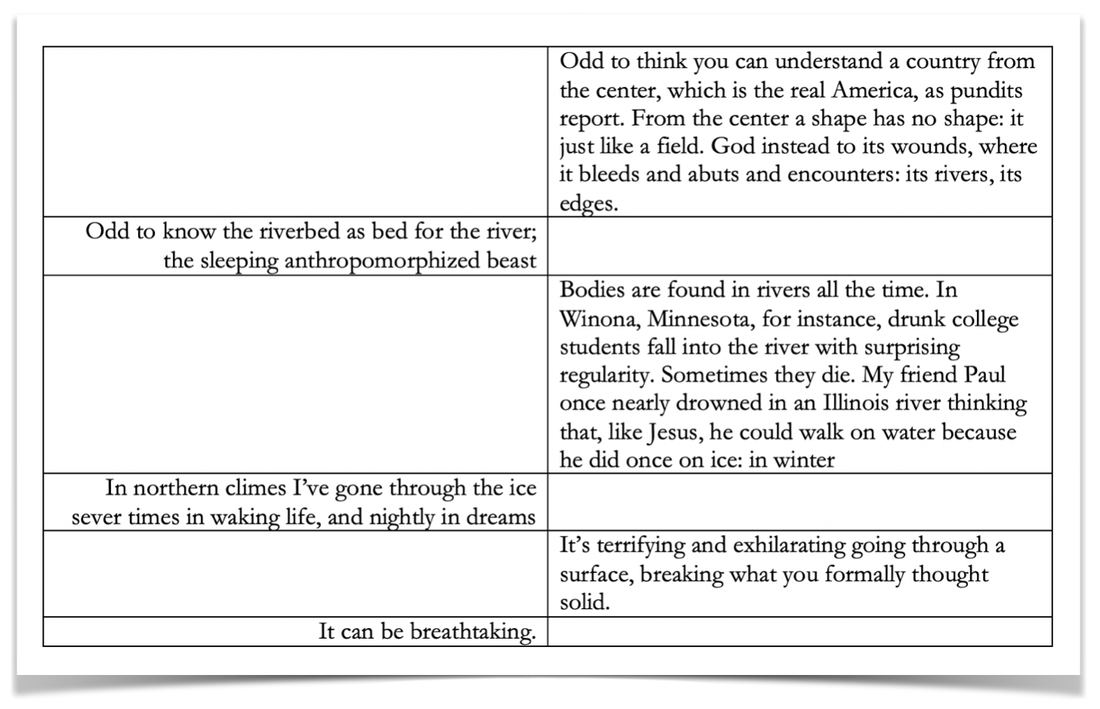

Four dimensional poetics aren’t limited to the world of poetry. Although the graphical and metric elements of poetry embody concreteness, nonfiction finds ways to make The Word be The Thing. Other elements pervade nonfiction to allow concrete readings—white space, of course, but also fragmented sentences, asterisks, assonance and consonance, repetition—but those aren’t as codified as they are in poetry and are rarely discussed as poetics, let alone concrete poetics. Ander Monson isn’t trying to catapult into Herbert’s heavens, usually. His God doesn’t live in the ethereal, abstract above. His lives in the tunnels beneath Tucson. In dry riverbeds. In the mineshafts of the Upper Peninsula. His new collection of essays, I Will Take the Answer, takes what was vivid and multidimensional in “I Have Been Thinking about Snow,” and takes it to a syntactical, visceral level. With snow, Monson had the luck of dots. Enough dots together surpass the ellipse and begins to blur like a blizzard. In the essay, the “I in River,” the weightiness of water surges toward the spine of the book. Spines of books become wet. They become a problem. Everything rolls to the middle: As the words puddle toward the middle of the page, we get a slanted scope of what it’s like to be in this icy, watery world. Monson’s subject is drowning, ice, politics, dreams, but it’s also the meta experience of letting words tumble forth and slide toward the gutter, into the arroyo, the riverbed.

As Monson writes this essay called “I in River,” he’s already set what some would call a double entendre. Double entendres are supposed to do with sex but my students use the phrase to mean anything that signifies in one direction, then another. Monson points to the letter I in the middle of the word river. He describes the I as looking something like the inside margins of a book. His I though is also the I of the essay, the narrator walking along an empty arroyo as the water (words) burble toward him. __________

Once we’re baptized into this C(c) oncrete space, nothing doesn’t signify doubly. As the left column of the text swirls around the subject of bed, we have river bed and also the bed upon which we sleep where we dream about drowning. On the right side of the text, we break through that ice that may drown us but we also have a breakthrough—we see the word as a wound. The word of God as a wound. Jesus’s words are wounds and we transcend. We breakthrough. On this side of the ice, we breathe.

If there is one kind of transubstantiation that both Herbert and Monson are going for, it’s the kind where the words turn three dimensional and you can eat them. Here is the blood of my body, says Jesus. Jesus hands you a cracker. Here is the body of my book, says Ander. Ander hands you the wet spine of a book. Delicious fiber. Following another concrete essay, “Is That What’s Behind the Dam,” is “Remainder.” Chunked into nine sections, the book goes down down down into the darkness of the mineshaft which also doubles as the mind space and memory space (make a memory palace—a real map for memories) of our narrator which then also doubles for following a map which doubles as the thickness and weightiness of text of text. This time, instead of words puddling and amassing, they pull with gravity, a weightedness similar to snow. In this essay, Monson maps mines. In the "Fifth Descent," he writes, Remove mind from remained and you get read, which is what I mean to do. I mean to read the remainder of the mine, what’s left of it in earth or memory, what I take away from home (another kind of mining, this taking away); my reminder of where I’m from. It’s not surprising that he who writes a map is the editor-in-chief of the literary magazine DIAGRAM.COM which publishes not only fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, but schematics. Monson turns schematics into words. He turns words into dimension by driving the eye diagonally, by plunging us shaftward. By breaking apart the words like cracking lodes into smaller chunks of copper or coal, their remains read in the map. What we can’t know, how to read a map, where the lode is, what the fissure signifies both in lode and a metaphor for absence, this big hole of nothing in the earth and in the paragraph, Monson argues fall in. Read the signs as you drop.

In the final essay, “Ninth Descent,” we arrive upon the epistemological question, what we can know. Monson traces his own home at night, certain of its contours, careful of its fissures. Monson has traced this mining town from 5000 CE through the Ojibwe’s copper collecting to the first European’s arrival in 1667 to the Paulding’s Light which is a “deeply freaky set of lights that emerge each evening and that, according to the lore, are spectral emanations—the ghosts of miners on the horizon trudging to their death” (69). It takes time for Monson to fully articulate the depths of the freakiness, the expanse of the mine shafts, the history of the territory. In the sixth descent, Monson admits he’s working on the metaphor, “It’s a cipher for me, a feature of geography, but what the mine represents is something else: the big hurt of the place, it’s most important myth” (66). And, at the end of that chapter, “The map is a map of history. We drill down. Excavate the horizontal until it becomes clear we’ve reached the structural limits or the end of the lode. Drill down again. Haul out rock and ore. Dump it in the lake. Repeat” (67). It’s a bit like writing, this drilling down. It’s a bit like excavating a self. It’s a bit like a ritual. You do it again and again, biting through the solids, until you get to that transcendent, hollowed out, abstract place. I love George Herbert. “Love Bade me Welcome yet my soul drew back, guilty of dust and sin,” runs through my head every day. I love the idea of poems shaped into Easter Wings and Altars that can catapult me from stony earth to ethereal heaven. But I don’t get to spend enough time in there. Perhaps if I were a believer, I could entrust the words and the image to combine and presto me forward into salvation. And while Monson isn’t offering me salvation, he is offering me a four-dimensional reading of the book, the river, the mine, and the memory. It takes time and weighty paper to play them all out. When I teach creative nonfiction, I tell my students to put their body in a place. That that’s how you transport your reader into your space. But using the lens of Monson’s essays, I also see that ability to “move the reader via the word” is the same work Herbert works in his altar poems. To enact a scene of the narrator cutting branches from a juniper tree does some of the transporting. But Monson’s essay shows that you can express more fully that movement, that body, by asking the text and the white space surrounding to do a little more work. You can use lines like axes and feathered sentences like branches. As in poetry, every decision, from dash to syllables, reinforces the reading you were hoping for, and does to work to take the reader to the place you were hoping to take them. |