ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

2.1

2.1

|

Flip the pages of your story over and write a draft from memory. Rewrite your piece by fleshing out summary as scene and turning scene into summary. Double your essay’s length. Write the initial version of the book longhand, and as you type it, revise. Draw diagrams. Make lists. Change POV. Change tense. Cut your writing into paragraphs, throw those paragraphs into a pile on your floor, shuffle them, and then tape them back together in a new and improved order. Or, why use paragraphs as the base unit? Get a cross cut shredder.

I won’t say that I hate revision, but I will say that I am deeply skeptical of revision as a culture. I think most of us write first drafts that are inspired and already close to being whatever it is they intend to be. We write early drafts largely without tons of active thought, from the gut, marveling at where it could all be coming from, the answer probably being actual bacteria in the gut. At least that seems as reasonable as any other explanation. And maybe because the amoebae (or whatever; I’m no microbiologist) use us only as conduits, some of us wind up a little depressed. Because the bacteria are brilliant—just check out their spot-on observations of human psyches. We? Not so much. We don’t exercise much control over any of it. Hence: revision. That’s where we get to diagnose, shape, cut, tweak, pick synonyms with better sounds, remove all of the em dashes (we heard that agents and editors read the title of that article on Slate and have decided em dashes are totally bush league). And through all of this maneuvering, we take the helm. We take control. We take credit. We affirm that we are the brilliant chroniclers of the modern age. We are. Not some batch of quasi-sentient organisms living in our small intestines. I suppose I distrust the need that might underlie revision. I distrust ego. Or at the very least, I distrust my ego, and my self-absorption and tendency to project make me distrust your ego, too. That said, I’ve run across, or maybe birthed the nightmarish vision of, another revision exercise to throw on the pyre—one that can potentially improve rhythm, possibly add a layer of thematic complexity, and more than likely destroy any confidence you may cling to that individuals are endowed with freewill. __________ One day, I read Ted Kooser’s essay “Hands,” which appears in the anthology In Short: A Collection of Brief Creative Nonfiction, edited by Judith Kitchen and Mary Paumier Jones, for a studio course in creative nonfiction. In Kooser’s piece, a persona contemplates seeing his father’s hands sprouting from his own arms, except in a much more poetic and less disturbing way than the word “sprouting” might suggest. I read along, floating on the imagery and sound, the general beauty of the thing, when I ran into this sentence: “They are exactly as I remember them from his own middle age—wrinkled, of course, with a slight sheen to the tiny tilework of the skin; with knotted branching veins, and with thin dark hair that sets out from beneath the shirtcuffs as if to cover the hand but that within an inch thins and disappears as if there were a kind of glacial timberline there.” I ask you: what the hell is that? It’s jarring and unwieldy, is what it is. If you’re not familiar with Ted Kooser, he was the 2004-2006 U.S. Poet Laureate, the Pulitzer Prize winner for poetry in 2005 for Delights and Shadows, and he’s won more awards than one can easily name. If any of us do anything on purpose, presumably Ted Kooser writes things, even jarring and unwieldy things, with total purpose. This is why my first assumption about how that sentence came to be was that a writer as gifted as Kooser understands the value of sentence variety. As a master poet, he considers meter and avoids tick-tock repetition. But could there have been more to it than that? __________ |

|

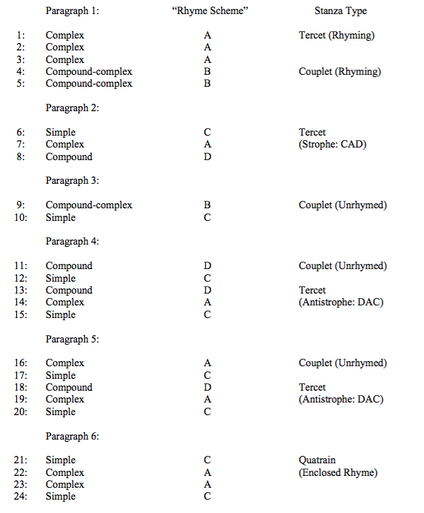

In order to better understand how that sentence came to be, I went through the rest of the essay with a pencil, trying to determine each sentence’s type (see the first column of Appendix A). As you’ll note, Kooser is, indeed, mixing it up, keeping the reader from falling into a trance, from being hypnotized by rhythm and deadened to content. But there also seems to be something else happening. Because I am the sort of person who tries to memorize series of blinking lights, like those on Christmas trees or marquees, I noticed that, in addition to sentence variety, the piece contains a strategic lack thereof, in the repetition of sentence types in the first and final paragraphs. The former features three consecutive compound sentences followed by two compound-complex sentences. In the final paragraph, we find two complex sentences bookended by simple sentences. What makes this notable is the lack of repetition elsewhere in the essay. No other paragraphs use the same sentence type twice in a row. |

|

The obvious next step, of course, was to assign each sentence type a corresponding letter. Using the order in which the sentences appear, I assigned the following letters as sentence-type indicators (see the second column of Appendix A):

A: complex B: compound-complex C: simple D: compound |

|

And then, after isolating each paragraph to its own “stanza” and roughly equating the order of sentence types to a rhyme scheme, what I found was that while the paragraphs between the first and last avoided repetition, an overall pattern emerged. In the second paragraph, we find three sentences in this order: simple, complex, compound. In paragraphs four and five, we find that same order inverted by the final three sentences in each: compound, complex, simple.

Because of these patterns, the essay as a whole could be seen as reminiscent of a Greek play’s strophe and antistrophe, moving linearly in one direction (tercet, couplet, tercet, couplet) and back again (couplet, tercet, couplet, tercet) before the piece ends with a quatrain—an enclosed “rhyme” of C-A-A-C. A golldang coda. Meaning that we do not return to the pattern found at the beginning of the piece but instead reach a point of transformation. But does all that patterning function with relation to content in some way? We could understand the first paragraph’s “rhyming” as a device that hypnotizes and draws us in. The pattern, the tick-tock, grounds us. Lulls us. That’s important, because we’re going to inhabit a persona whose father’s hands are about to sprout from his own wrists. We’re about to traverse back and forth through time, space, and geography. When you think about it, that’s pretty wacky. Pretty unlikely. Pattern is what produces the initial effect of plausibility. In the next paragraph, when the “rhyme scheme” appears on the surface to be fairly scattershot, when the patterning disappears, the persona takes us into a state of disorientation. He asserts his hands are not his: “I recognize [my father’s] hands despite [my] ring. They are exactly as I remember them.” From there, we drift out of our grounding in the persona’s body, we encounter that mind-boggling sentence that started this whole analysis, and we see a snapshot of the father as a fabric salesman. When we return to the persona, briefly, he states, “I can feel the little swirls of brocade beneath the ball of his thumb.” Meaning: I can feel through someone else’s sensory organs. We’re feeling brocade through someone who feels brocade through someone else’s thumb. The intermixed embodiment of the persona and the persona’s father continues through the first part of the fourth paragraph, when the hands are no longer the father’s or the son’s but simply “these.” By the end of that paragraph, both characters have been supplanted by “hands like these—some brown, some black, some white—in every bazaar in the world—hands easing and smoothing, hands flying like doves through the dappled light under time-riddled canvas.” These hands, in other words, are all hands. In the penultimate paragraph, the persona is embodied in himself again, but the hands that we might think would unify him with his father seem to be what separate the two men. These hands can’t hold the persona to his father’s breast. These hands, in being his father’s, paradoxically create a distance that can’t be bridged. As the piece ends and its final stanza returns to a more overt rhyming pattern, the first and only quatrain of C-A-A-C, the hands belong to the father wholly, as we see in the phrase “these old hands of his.” They do not obey their current owner; they “move on their own.” The persona watches as “the left hand slowly [rises]” and watches again as “the right [rises] swiftly to enfold the other.” In other words, there’s been no tidy return to a persona looking at his own hands and recognizing in them the hands of his father. These are simply no longer the persona’s hands. Ergo, recognizing another in ourselves is akin to dismemberment. Had we been given a cyclical sense of embodiment, entering into the persona again fully at the end, I suspect the piece would have been more anecdote than essay. Had we ended on a note of negotiated, shared embodiment of father and son, the denouement would have been a big, decorative bow. For either ending, we might reasonably expect a return to the pattern in the first paragraph, maybe with the rhyme somehow inverted (e.g., B-B-B-A-A). Instead, though, this is all there is. This coda. The persona hasn’t returned to where he was at the beginning with some new knowledge. He’s changed. The persona at the beginning of the piece no longer exists, even physically. What we might wind up with, then, is a meditation on empathy—possibly a lament regarding its incompleteness, a statement about how empathy only reminds us of just how distant and separate we all are, or maybe an observation that, if it were possible for one to fully empathize with another, the self would be lost. __________ Okay, but what of this bizarre exercise? What might it all mean? And do I really think Ted Kooser analyzes his prose for sentence types and then patterns his essays according to how they might translate into tercets and strophes and codas and the like? In short, I would hazard that he does not. And aren’t those patterns likely there (if they are there) just because any given language has a circuitry and rhythm? And/or might those patterns be there because we instinctively imitate the structures of what have been considered enduring texts? And/or might we not find beauty in symmetry and therefore subconsciously pattern pieces in such a manner? And/or might we see patterns in there because we are predisposed to find patterns as some kind of survival mechanism? Yes, I think that’s all pretty probable. So then do I really think that we should perform something along these lines when we are revising? I think this analysis shows that it’s a fully entertainable notion to say that, whether crafting poetry or prose, Ted Kooser has some wiring that embeds these patterns. We all likely do. Meaning that they are a part of our nature. Our programming. Our innateness. They might be why Ted Kooser is a poet to begin with (or vice versa). When we talk about writing, we often use terms like “flow” and “voice,” nebulous concepts we can’t (and maybe shouldn’t) fully and satisfactorily define, ideas that encompass but also stretch well beyond diction and into language characteristics that are no doubt as individual as DNA. The number of syllables we use. The meter. The larger, more obscure patterns created by our sentence types. I don’t know that these concepts can ever be used in all that prescriptive of a way, since I’m not sure we have very much control over them. But I do think that this sort of exercise can help us hear our voices in ways we might not otherwise, and in a brief, minute existence wherein many of us spend some time feeling disembodied and unfamiliar with ourselves, why not? Maybe the psychic divide between ourselves and other selves has less to do with subjective experience than it does with a lack of any real self-empathy—with walking around and taking for granted that we know ourselves, like the self is some static, boundaried thing. And, of course, if all else fails, if a moment in our writing isn’t working and all of the bacteria have thrown up their tiny rod-hands and have begun to gnaw on a bit of orange slice, by looking at patterns in this way, we may find what is hanging up, what is too monotonous, maybe what is too pat. |

Click here to download a printable PDF with Works Cited.

|

Chris Harding Thornton holds a BFA and an MFA in fiction and a PhD in English with a creative writing emphasis. She is currently revising her first novel, Reclamation, as well as a book-length work of creative nonfiction, The Road to Thacher. She teaches writing and literature courses at University of Nebraska.

|