ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

4.2

4.2

|

My advanced creative nonfiction students came to class one day recently with their eyes big and wild. They dropped their backpacks and threw up their hands in a fit of pre-writing I knew well. “The immersion assignment,” they howled. “It’s too big. It’s out of control! It didn’t go like I planned!”

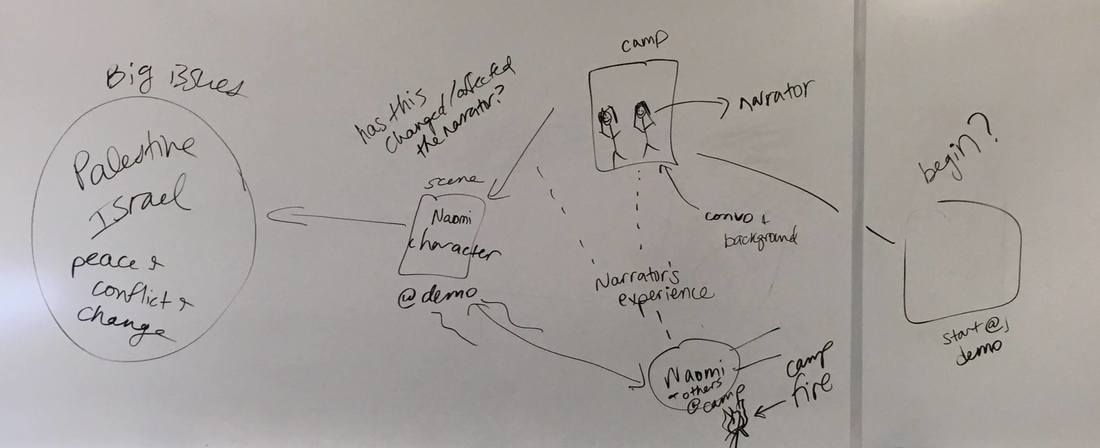

“Perfect,” I told them. “This is exactly what is supposed to happen.” For a brief minute standing up at the whiteboard, I stepped out of craft and grading mode. I drew a heart on the board and wrote “vulnerability to subject.” That wasn’t on the lesson plan, but I decided to go with it, because I was realizing something in the moment. And this was exactly their challenge as writers. My extended immersion project aims toward the goal of producing a longer essay in which the narrator intentionally steps into the story as it’s happening. The essay is the mode of inquiry, from subject-selection to research and writing, and the essay is the genre of the finished piece. We think of journalism as looking “out” at the world, and memoir as looking “in,” and this assignment requires one eye trained inward and one eye looking out at the world. Think of Thoreau, I told them, going to live in the woods to see what he could see and write about it, or John McPhee, setting out with himself and his curiosity. The most perfect expression of the form I’ve read might be Adriana Páramo's Looking for Esperanza, which begins with the author reading a newspaper article about a woman crossing the border from Mexico with her children and having to leave a dead infant somewhere in the crossing. Páramo—with no guarantee of success—simply set out to find her. Other great examples include James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men—a classic about immersion with sharecroppers, Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks--a research journey about the intersection of science, race, and society that becomes personal, and Steve Almond’s Candy Freak—a love affair with candy turned into a road-trip to find mom-and-pop candy factories. I usually use Robin Hemley’s book, A Field Guide for Immersion Writing: Memoir, Journalism, and Travel. Instructors who’ve taught composition for a while will also connect this to the I-Search Paper, a fantastic composition assignment and framework by Ken Macrorie, and my own Backwards Research Guide, which is also centered around the same basic approach for use in composition classes but with more quotes from Buddhists. The scaffolding for it takes all semester. First I assign the project and orient them to the form, and then they have staggered due dates for each step of the essay, which is due about ten weeks into a fifteen-week class. I launch the experimental essay project at the same time (it’s a bit of juggling) so that we get that done with while their immersions are brewing or rising or fermenting. It ends up that they’re workshopping experimental essays while they’re writing their immersions. “What’s something you’re curious about or connected to but have never done?”To start, I ask everyone to bring in three or more ideas to class, and we put them all up on the board. Students can claim one that they want but the rest are up for grabs. What we do for that whole class period is to think about activities that they might not otherwise do that allow them to experience something new and thought-provoking. Students propose questions, ideas, and stunts: live a week as a good Catholic, talk with seniors at a senior center, shadow a friend who works at a charter school, do a ride-along with a local police officer, or to eat a meal plan prescribed for an anorexic friend in recovery as a way to understand the friend’s experience. I tell them about my current immersion project (four years and counting) of walking the border between Bridgeport and Fairfield in Connecticut to observe and meditate on socio-economic disparity as a way to stress that a simple visit to a place, once or repeated, builds a structure for an immersion. Many of them focus on interviews, too.

“Three out of my four best friends are anorexic. I’ve never understood their aversion to eating because I love food. All three of my friends have a connection with each other that I’m not a part of because I don’t understand anorexia. I don’t understand why eating is so difficult, I don’t understand body dysmorphia, and I don’t understand my closest friends. This disconnect especially damaged my friendship with one of my friends who was my roommate the first year and a half of college. I witnessed her lose more and more weight until she was forced to leave school in the first semester of sophomore year because of her unhealthy weight. I never recovered from this separation. When my friends were recovering, their doctors assigned them a special meal plan to help them gain a healthy and wholesome appetite. Perhaps if I tried this meal plan and interviewed them, I could understand their struggles with eating and what led them to anorexia. I need to understand them to bridge the gap between us.” —Carlye Mazzucco

|

|

Sonya Huber is the author of five books, including Opa Nobody, Cover Me: A Health Insurance Memoir, and the new essay collection Pain Woman Takes Your Keys and Other Essays from a Nervous System. She teaches at Fairfield University, where she directs the low-residency MFA program.

|