ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

9.2

9.2

|

From another epic another history. From the missing narrative.

From the multitudes of narratives. Missing. From the chronicles. For another telling for other recitations . (Dictee 81) What does it mean to write and speak in a language which is not your own? And as a writer, how important is it to feel a sense of literary heritage or ancestry, which one is connected to, is able to access and feels part of? These questions came to mind when I first encountered the writing of the Korean-American poet, writer, film-maker, producer and visual artist, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-1982), and in particular, her most renowned work, Dictee (1982).

Dictee is a profoundly elusive, complex and deeply personal text. Interdisciplinary in its content and form, it incorporates elements of autobiography, prose, poetry, photographs and documents. From the start, the inclusion of certain images, charts, Chinese characters, anatomical diagrams as well as other forms of written text subverts the reader’s expectations with regard to textual representation. What makes this work truly remarkable and unique is how it navigates the vast, emotional terrain of individual, historical, political and collective imaginaries as well as its violent realities. Cha was born during the time of the Korean War in 1951, in Busan, South Korea, the middle daughter of five children. At the age of 12, she emigrated to the United States with her family experiencing first-hand the effects of loss, exile, migration and displacement, which were later explored in her creative work. Given the scope of Cha’s intellectual interests and scholarly achievements, the seriousness and intensity of her artistic output is unsurprising. During the 1970’s she completed four degrees from the University of California at Berkeley: a B.A. in Comparative Literature, a B.A. in Art, an M.A. in Art, and an M.F.A. in Art. She also had an interest in film and studied film theory at the Centre d’Etudes Americaine du Cinema in Paris in 1976 under the tutelage of Jean-Louis Baudry, Raymond Bellour, Monique Wittig, and Christian Metz. Despite the fact that her life was tragically cut short at the age of 31, Cha left behind a rich legacy of work that was informed by a diverse range of cultural, theoretical and symbolic references including French psychoanalytic film theory, linguistic theory, Symbolism, concrete poetry, Korean cultural traditions and shamanism, Catholicism and Confucianism. As a Korean-American writing about female experience from a variety of perspectives – maternal, mythical, historical and mystical – Cha has had a discernible influence on Asian-American/British contemporary poets such as Cathy Park Hong, Bhanu Kapil and Ocean Vuong. In Minor Feelings: A Reckoning on Race and the Asian Condition (2020), Hong includes a full chapter on Cha entitled Portrait of an Artist in which she reflects on her legacy and the violence of her death. Just a few days before the original publication of Dictee, Cha was murdered and raped by Joseph Sanza, a security guard who was known to her, as an employee in the building where her husband was working at the time. Hong draws attention to the silence that shrouds Cha’s death, which gives Dictee a “haunted prophetic aura” and the “baffling” contradiction between the ways in which “scholars will argue how Cha is recovering the lives of Korean women silenced by historical atrocities while remaining silent about the atrocity that took Cha’s own life” (Hong 155, 157). Hong further discusses the extent of Cha’s importance to her in terms of language, particularly in terms of a shared Korean-American identity and how English, as an inherited language, operates, in part, as a form of oppression: Cha spoke my language by indicating that English was not her language, that English could never be a true reflection of her consciousness, that it was as much an imposition on her consciousness as it was a form of expression. And because of that, Dictee felt true. (Hong 155) From the outset, Cha explicitly draws a connection between language and the body, the “ability and inability to speak” (Cha 56). The epigraph to Dictee testifies to the influence of Ancient Greek myth and lyric poetry in its reference to a quotation attributed to Sappho, “May I write words more naked than flesh, stronger than bone, more resilient than sinew, sensitive than nerve.” The later invocation to the Classical Muses, “O Muse, tell me the story/Of all these things, O Goddess, daughter of Zeus/Beginning where you wish, tell even us,” in itself a reworking of Hesiod’s invocation of the Muses in The Theogeny, situates the placing of epic and lyric traditions of poetry in juxtaposition (Cha 7).

|

|

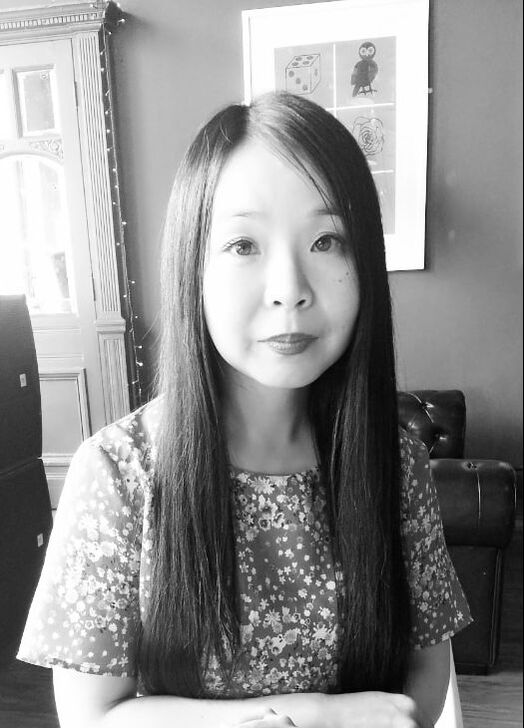

Jennifer Lee Tsai is a poet, editor and critic. She was born in Bebington and grew up in Liverpool. She is a fellow of The Complete Works programme for diversity and innovation and a Ledbury Poetry Critic. Her poetry and criticism are widely published in magazines and journals including Poetry London, The Poetry Review, The Telegraph, The TLS, The White Review as well as in the anthology Ten: Poets of the New Generation (Bloodaxe, 2017). Her debut poetry pamphlet is Kismet (ignitionpress, 2019). In 2019, she was awarded an AHRC scholarship to undertake doctoral research in Creative Writing at the University of Liverpool. She received a Northern Writers Award for Poetry in 2020. Her second poetry pamphlet La Mystérique (2022) is published by Guillemot Press. She is a winner of the 2022 Women Poets’ Prize.

|