ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

4.2

4.2

|

“I don’t discover the structure except by writing sentences because I can’t think structurally well enough.”

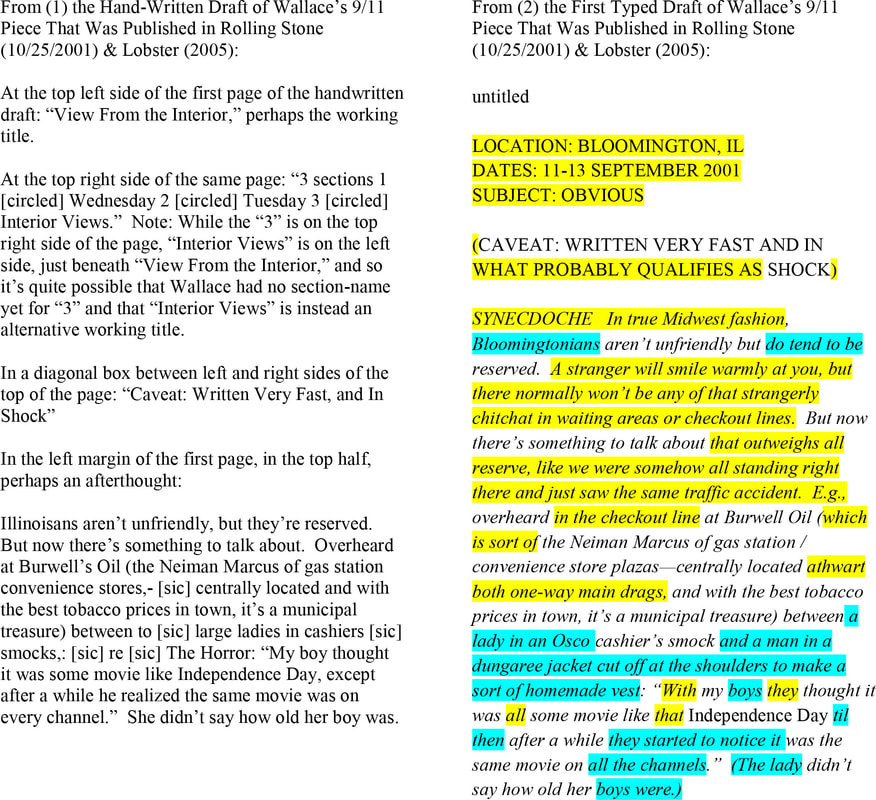

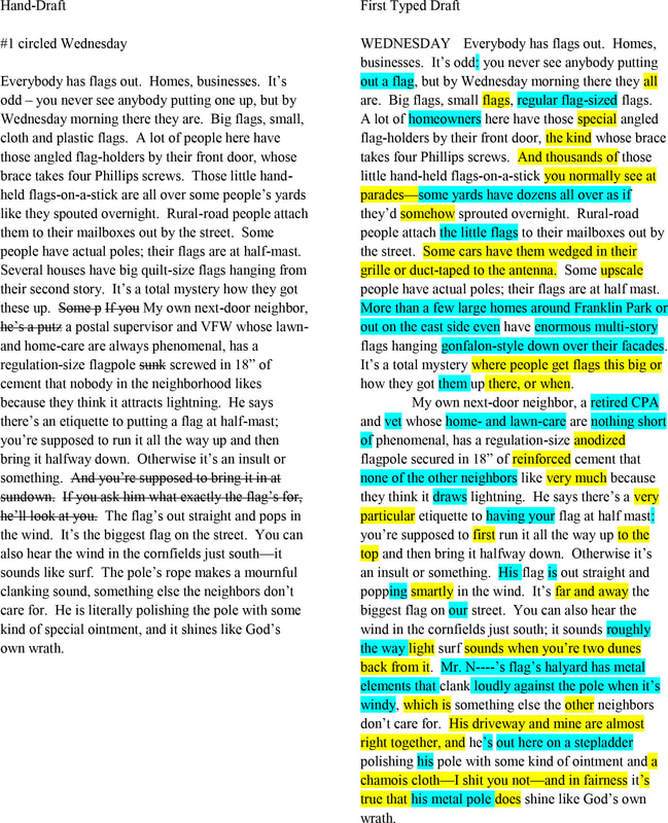

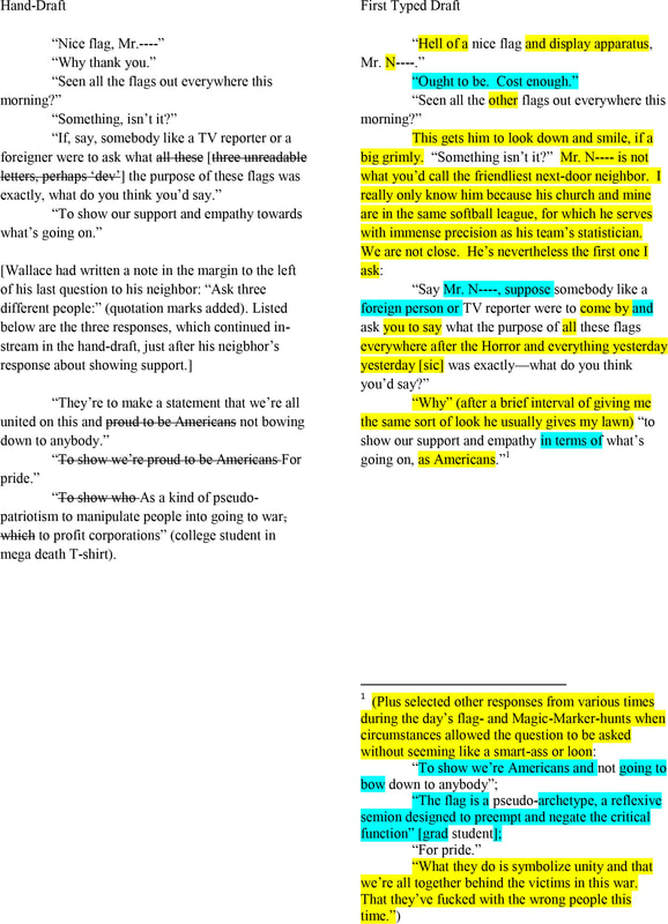

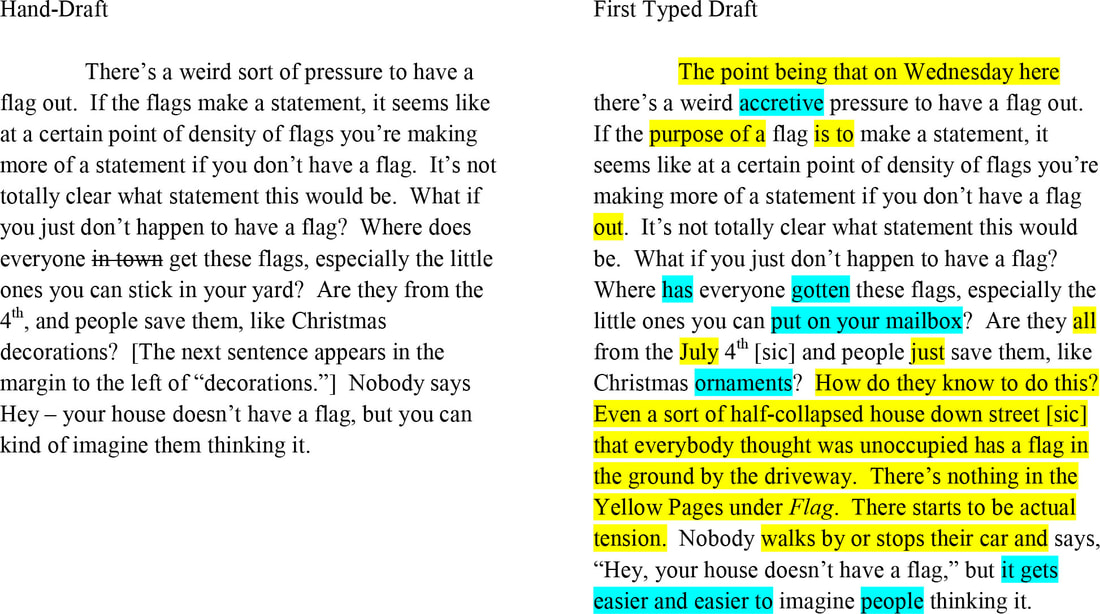

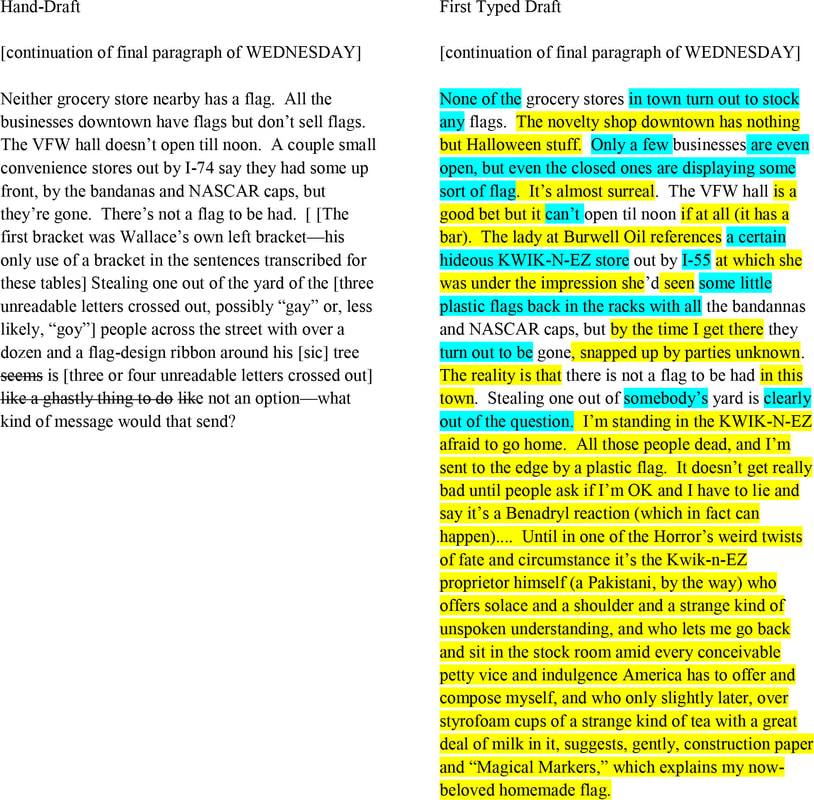

—David Foster Wallace, Quack This Way On reserve at the Harry Ransom Center (HRC) at the University of Texas is the archive of David Foster Wallace, which holds various drafts and proofs of the writer’s oeuvre, including both fiction and nonfiction [1]. Much scholarship has been devoted to Wallace’s fiction; less to his nonfiction. This essay is interested in the latter, in particular Wallace’s piece on 9/11 for Rolling Stone, “The View from Mrs. Thompson’s” (Oct 25, 2001). Multiple versions of it are on file at HRC, including, in one folder alone, Wallace’s handwritten draft, a largely pristine typescript draft, an edited version of the typescript, and a copy of the article that appeared in Rolling Stone [2]. Wallace did fairly light editing in the second typescript: just a few word changes and the striking of a paragraph that he restored for Consider the Lobster. Rolling Stone, for its part, changed very little from this second typescript. Nearly all change takes place between Wallace’s first two drafts. And so this paper will devote most of its attention to the difference between the handwritten draft and first typescript, in particular to changes Wallace makes to his sentences. By honing them carefully, Wallace finds his way inside the story, understands its structure more deeply, and enables himself to turn an incomplete rough draft into a thoughtful, polished essay. While such a process is not without precedent, the degree to which Wallace trusts his sentences to lead him from darkness to light is rare, warranting a close look by nonfiction writers and scholars alike.

|

|

|

Michael W. Cox teaches creative and professional writing at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. His scholarship has appeared in Midwest Quarterly, South Asian Review, and Explicator. His nonfiction has appeared in New Letters, Sport Literate, River Teeth, Kestrel, the New York Times Magazine, Best American Essays, and the Touchstone Anthology of Contemporary Creative Nonfiction. His novel The Best Way to Get Even was recently published by MAMMOTH books.

|