ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

2.2

2.2

Most of rap’s stories are neither incisive social commentaries nor thug fantasies. Like most stories throughout the history of human civilization, most of rap’s stories are occasions to imagine alternate realities. To hear rap’s storytelling at its best is to experience liberation from the constraints of everyday life, to be lost in the rhythm and the rhyme. Rap’s greatest storytellers are among the greatest storytellers alive, staying close to the tones of common speech even as they craft innovations on narrative form. Rap’s stories demand our attention not simply as entertainment, but as art. (Bradley 158) |

|

Persona is a narrative creation that paints a picture of a character composed of many elements, and those elements can be crafted by the author, or shaped by the personality of the character that was formed by the forces surrounding them during their development within the story. In The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Alex Haley was careful not to go too far outside convention when writing the life story of the civil rights era icon. In and of itself, Malcolm X’s life in narration is an adventure and story worth reading. It gained meaning from the struggles he brought forth to the open, in a voice that resonated against the portrait painted of him in the media. People responded by wanting to know more about the man. In the same way the civil rights era frames Malcolm’s story and gives credence to his persona, the popularity of rap plays a similar role in shaping the autobiographical persona in the memoirs of two popular hip hop artists, Jay Z in Decoded and Questlove in Mo’ Meta Blues: The World According to Questlove.

What ties these three nonfiction narratives together is that their lives portray aspects of the effects caused by the African slave trade to America. It was through the suppression of creativity and human dignity that the ancestors of these men provided them with the internal motivation to push forward and break through the barriers that have held back African Americans for so long from living a life not as the outsider, but as a member of the society that built this country and created an abundance of its cultural legacy. These memoirs, written by two famous artists in hip-hop, represent the genre from two divergent backgrounds. Under the banner of hip hop, Jay Z and Questlove have shown that rap is more than a one dimensional genre, relegated to the harsh realities in the confines of ghetto literature, and interpreted as a bastion of immoral social upheaval by the upper echelons of class. Clearly this discussion must, on a larger scale, acknowledge the distance between the writer and his co-author as these narratives seek to create personas separate from the men themselves, but this consideration is the role of public vs. private persona in popular culture memoirs, particularly those of black men. Jay Z frames his success story by giving the reader a glimpse back to when things were not so great for him. In addition, he gives readers the words that he used to elevate his mind and teach his audience what it means to see the world from his point of view. He offers these lessons in clever rhyming metaphors that contain past and present elements to which the reader can relate, especially because he takes the time out to define the content of his poetry in footnotes, an important melding of rap and literature. Questlove’s approach to the genre is a chronological jukebox, expressing the ups and downs of his personal life, as well as those of his family and band members. Adam Bradley in Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip Hop takes into context the myriad of viewpoints that sum up the rap artist’s experience: Between the street life and the good life is a broad expanse of human experience. Rap has its screenwriters, making Hollywood blockbusters in rhyme with sharp cuts, vivid characters, and intricate plotlines. It has its investigative reporters and conspiracy theorists, its biographers and memoirists, its True Crime authors and its mystery writers. It even has its comics and its sportswriters, its children’s authors and its spiritualists. It is high concept and low brow; it has literary hacks and bona fide masters. It has all of these and more, extending an oral tradition as fundamental to human experience, as ancient and as essential, as most anything we have. (158) |

|

Click here to download a printable PDF with Works Cited.

|

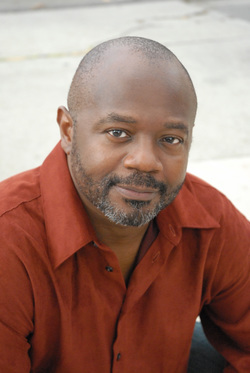

Lawrence Evan Dotson is a writer and freelance film professional in Los Angeles, California. He recently received an MFA in Creative Writing with a mixed concentration in Creative Nonfiction and Poetry, from Antioch University Los Angeles. In 1991, he started a twelve-year career as a hip hop journalist during what is known as the Golden Age of Hip Hop. Under the pen Name “Loupy D”, he wrote and edited articles for two well-known LA underground magazines, (No Sellout, Kronick) and one national magazine (RapPages). Currently, Lawrence is the music editor at Drunk Monkeys and has a blog called Loupy D in the 21st Century (www.loupyd.com). He’s a single dad of two boys.

|

Related Works

|

Micah McCrary

A Legacy of Whiteness: Reading and Teaching Eula Biss’s Notes from No Man’s Land: American Essays 2.2 Articles |