ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

1.2

1.2

|

Conventional wisdom would have us believe that poets and novelists are the only kinds of writers who have muses—or need them. Given the current educational climate, however, in which we teachers and our students must exist, one might argue that nonfiction writers need muses most of all.

With so much focus in high schools now on testing and on the scores generated by writing assessments, especially with the formulaic, survivalist kinds of writing that proliferate, many students come to our college composition classrooms believing that nonfiction writing is a sterile landscape ruled by clear thesis statements, strong topic sentences, and supporting detail. All of us know, however, that the best nonfiction writing—composition, rhetoric, creative writing, critical writing—transcends formula. All good writing draws its power from story, craft, and insight—elements most traditionally associated with the metaphor for creative inspiration we call “the muse.” Rather than waiting for muses to appear through magic, chance, or divine intervention, I’ve found that finding one’s muse is a process that can actually be facilitated and taught. I’ve been using writing marathons as a pedagogical tool for about eight years, in high school and college composition classrooms as well as with graduate students and practicing teachers. I’ve seen them provide the motivation and sense of agency that helps struggling writers find their voice and helps good writers expand their gifts. This past summer, though, was the first time I ever contemplated the relationship between marathons and muses, particularly in terms of what this relationship might mean for writing pedagogy. Themed “Finding Your Muse in New Orleans” and hosted by the Southeastern Louisiana Writing Project of Southeastern Louisiana University, this retreat was the fullest expression, to date, of the writing marathon technique developed by Richard Louth, Professor of and English and SLWP Director at SLU, over several years following the first one in 1994. Louth piloted the first “New Orleans-style” writing marathon in 1994, and the idea has since spread across the country, with marathons practiced now in at least 100 National Writing Project sites, in classrooms and writing groups, at literary festivals and youth camps. I’ve facilitated and attended dozens of writing marathons and also studied and written about the technique in depth, so I was invited to the retreat as guest speaker on a panel about marathon pedagogy. As a retreat participant, however, and especially within the immersive, five-day retreat experience, I discovered several new things, particularly a nonfiction writer’s need for muses as much as—or maybe even more than—other writers. Additionally, the retreat helped me understand why marathons work so well for nonfiction writing teachers: because they function as a kind of “meta-muse” that opens the door for student writers to find their own muses. Marathons do this by combining three key elements: 1) the luxury of a time set apart from regular class, 2) a supportive community writing together and providing an audience for one another, and 3) the immediate, sensory experience of the world through writing in a sequence of places. Through this simple but powerful protocol, and especially through repeated practice, writers develop a technique for what many (including our retreat writer-in-residence Kim Stafford) have called “tuning in” to the world. We tune in to that special writer frequency where we can hear muses everywhere—in people, places, sounds, foods, scenes, smells, and in the subtle harmony of these things moving together and within ourselves. Because it allowed participants to dwell in this writerly mindset for several days, the New Orleans Writing Marathon Retreat also reminded me that—along with being an assistant professor, a teacher, a scholar, an administrator, and several other mundane things—I am also a writer. It reminded me of this cherished fact with the most visceral intensity I’ve ever experienced. As simple or self-indulgent as this notion may sound, claiming one’s identity as a writer is a vital part of a pedagogical stance at the core of the National Writing Project. In its 40-year effort to improve writing instruction in K-college classrooms across the country, one of several core principals guiding the NWP has been that the best teachers of writing are writers themselves. Jim Gray, founder of the NWP, calls the practice of this principal in NWP’s professional development models “the ultimate hands-on experience” (143), one that he intended from the organization’s inception to very explicitly “allow teachers to experience what they ask or should ask of their own students” (144). The New Orleans Writing Marathon Retreat returned me to my roots as a writer and, adapting the oft-quoted NWP adage above, it also helped me understand that the best teachers of nonfiction writing are nonfiction writers themselves. Too often the endless, non-teaching demands of our academic profession pull us away from doing the kind of writing we ask our students to do. We forget what it feels like to become interested observers of the world, of the real beings who live in real places, who struggle, flourish, spin stories, and enchant us into weaving our own. We also forget how powerful and engaging our own authentic experiences as writers can be in terms of modeling for our students, many of whom have rarely enjoyed the opportunity for the kind of field research and meditation that nonfiction writers do. As compositionists Chris Gallagher and Amy Lee remind us, “When young people are surrounded by adults who write in ways that matter—ways that make a difference in their communities—they are more likely to view and practice writing this way” (63). |

//

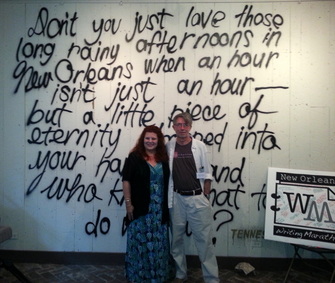

In the New Orleans Writing Marathon Retreat community of writers, we inspired each other to embrace the best of our writer-selves and to share stories that mattered to and to the city that hosted us. We gathered each day for morning services of “writer church,” workshops, writing, and talks with Kim Stafford before heading out into the world. All day we wrote, everywhere, in groups and alone, with local guides and on our own. We wrote in cafés and bakeries, gay bars and jazz clubs, under live oak trees and balconies, on ferries and on streetcars. Each evening before dinner, we returned to our home base at the Gallier House in the French Quarter, sharing our writing at a mic under a Tennessee Williams quote from A Streetcar Named Desire, scrawled in black spray paint on a bare white wall: “Don’t you just love those long rainy afternoons in New Orleans when an hour isn’t just an hour but a little piece of eternity dropped into your hands—and who knows what to do with it?” By the end of the week, my notebook was fat with writing seeds, already sprouting and spreading. Two of the pieces I read at the open mic evolved into submissions appearing in the current issue of Louisiana Literature, vignettes I’ve also shared recently in writing workshops, one with graduate students and one with fifth graders on a field trip to campus from a local school. Another promising seed, one I wrote on a the riverboat “Creole Queen” on the second day of the retreat reads, |

We cruise along, cradled in Mother Mississippi’s brown arms as the riverbanks slide past through the big windows on either side of the riverboat interior. A hulking Polish oil tanker looms and then fades under the gold-tasseled fringe of heavy curtains. Then the Domino Sugar factory and the rusting metal docks trail past in the molasses-sweet air. A young girl in a lime-green t-shirt with white-rimmed sunglasses makes her slow way along the outer deck. Then a long, red grain barge slinks by, nudged by a striped little boat called the “Belle Chase.” |

|

This particular piece of marathon writing may or may not develop into a longer work that may or may not prove meaningful for an audience beyond this moment. Yet, I will likely share it with my writing students at some point, an example of the kind of craft exercise that helps strengthen our writing muscles, builds confidence, stamina, and fluency while keeping us open to potential muses. As composition scholar Robert Yagelski has argued so eloquently, the kind of “writing in the moment” so central to marathons has value in and of itself—as nothing less than a way of being. “As we write,” he explains, “we engage in a moment of intensive meaning-making related to the larger process of making meaning as we experience ourselves in the world. Thus, the act of writing underscores—indeed, enacts--the deeper relationship between our consciousness and the world around us” (13).

The more writing marathons I attend and facilitate, the more this relationship makes sense to me, and the more I understand why marathon participants often use the term “magic” as shorthand for such powerful and complex experiences. The retreat helped me further understand that one reason marathons might be so popular and so successful in such a wide range of contexts is because they evoke (and invoke) different kinds of muses. Some of these muses keep us “tuned in” to the world’s many songs. Some become the subjects of songs themselves. As Yagelski suggests, marathons can also allow us to enact our own muses. At their best moments, however, I like to think that marathons are themselves muses that teach writers—nonfiction and otherwise—that they can serve a sacred function in the world. Stafford shared this function with us at the retreat, one he also explores in his book The Muses among Us: Eloquent Listening and other Pleasures of a Writer’s Craft. He explains that great writers serve not as prophets but rather as “those scribes resting near the prophets, ready to rise up at once and write what speaks” (7), as “instruments” who communicate their experiences of the world back to the world, for all to share. |

|

At the New Orleans Writing Marathon Retreat, dozens of such prophet-muses came and spoke to me and through me, day after day. Each one whispered a hundred truths, each truth the glimmer of an essay or memoir waiting to emerge:

An orange-tan celebrity in a seersucker suit jacket, shorts, and straw hat, fantastical in the fluorescent lighting from the beverage cooler, chatted up fellow patrons waiting for oyster po’boys in a narrow deli. |

|

Each one still whispers to my writing teacher-soul, reminding me of every piece of precious, rainy eternity we can help our students feel dropped into their hands.

Note: The New Orleans Writing Marathon Retreat will be offered again July 13-17. It is partially funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Supporting Effective Educator Development (SEED) Grant Program sponsored by the National Writing Project. Writers and teachers who would like more information about writing marathons should consult WritingMarathon.com, a website maintained by the Southeastern Louisiana Writing Project at Southeastern Louisiana University. It contains sample marathon writings, radio programs, and articles about marathons as well as teaching materials and guidelines for teachers and facilitators. Even more helpful resources can be found in the book The Writing Marathon: In Good Company Revealed, a collection published by the Southeastern Louisiana Writing Project and edited by Richard Louth.

|

Click here to download a printable PDF with Works Cited.

|

Susan Martens is an assistant professor of English at Missouri Western State University and director of the Prairie Lands Writing Project. Her work has appeared in College Composition and Communication, English Journal, Louisiana Literature, and is forthcoming in Writing Suburban Citizenship: Place-Conscious Education and the Conundrum of Suburbia from Syracuse University Press.

|