ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

6.1

6.1

|

The American Essay in the American Century Univ. of Missouri Press, 2011 |

Every reader, it seems to me, reads every text in a way individual to that reader. Each reader’s interpretation is influenced by who that reader is, what that reader has read before, and whatever circumstances or motives or needs brought that reader to that text. I don’t know if anyone still talks about reader-response theory— critical and pedagogical fashions are ever-changing—but I still subscribe to it, more or less. I once read that, if you read Don Quixote at five different stages of your life, you find it a different book each time. By now I’ve experienced that with various works.

All this came back to me as I reread Ned Stuckey-French’s The American Essay in the American Century hoping to contribute some thoughts about it while reacting to the impact of his death. I’d reviewed the book years before, when it was first published, and reread it without consulting that review in hopes of avoiding mere repetition, no matter how admiring. The “American Century” covered in the book runs roughly from the last quarter of the nineteenth century through the first half of the twentieth. It required a voluminous amount of reading on Ned’s part of all the American essayists, all the critical essays on the essay, and all the reviews of essay collections. It distinguishes among literary trends and simultaneously locates them in cultural and sociological contexts. I re-discovered how alert Ned was to the historical context of the essays he discusses, his awareness that an essay read in such a context makes us appreciate more profoundly what that essayist was thinking about when he or she wrote it. In the course of a thorough and wide-ranging historical overview, he makes it difficult for a reader to detach the individual essay from its era. All readers bring their own predispositions and prejudices and preferences to whatever they read; Ned manages to shift our focus to an appreciation of what the writer was bringing to a specific essay at the time it was written. He deepens our comprehension not only of what is being said but also of who is saying it. One of the factors determining how we read an essay is the way most of us have been introduced to it. Ned’s chapter on “The Essay in the Progressive Era” astutely traces the realignment of English courses by making literature courses increasingly upper level elective courses for English majors taught by scholarly professors and writing courses principally basic composition courses required of all first-year students and taught by graduate assistants and adjuncts. Attention to nonfiction writing emphasized its serviceability, its usefulness across all disciplines and contexts, essentially homogenizing prose into a universal sameness. In that chapter this shift seems a historical sidenote but a hundred-and-twenty-five years later it has pertinence for the politics and organization of English departments in the Post-American Century. In his epilogue Ned quotes Lynn Bloom’s assertion that “the essay canon is now fundamentally a teaching canon as opposed to a historical, critical, or national canon. . . . on the whole, essays serve as models used to teach nineteen-year-olds how to write.” He enlarges on her observation: Such teaching is hard work. New teaching assistants facilitate multiple sections of freshman composition in which they are expected to introduce the entire writing process from brainstorming through proofreading as well as remediate and sometimes even teach writing across the curriculum. Editors select essays for first-year writing anthologies with the needs of these young teachers and their students in mind. Is the selection current and accessible? Can it be used to model this or that rhetorical mode? Is it short enough to be used in a one-hour class? Is it in the public domain, and if not, how much will the permissions cost? Will it help diversify the anthology in terms of race, ethnicity, and gender? Does it help establish a balance between classic and contemporary essays? Between emerging authors and established big names? Those of us who have taught freshman composition and wrestled with the challenges of text selection will recognize the accuracy of Ned’s overview. He argues that the anthologies tend to include “shorter, simpler, and more ‘teachable’ essays,” often excerpting “longer, more layered, and more difficult essays,” “flatten[ing] and simplifying” them through the use of “headnotes, discussion questions, [and] writing prompts,” and making the personal essay a less literary genre. He points out that we teach essays as if they are timeless, free of the age in which they were written, and perhaps free of the background and circumstances of their authors.

Reading Ned’s book again eight years later, I found portions resonating with the times we live in now. One such passage quotes FDR’s assertion that “Whereas five years ago ninety-nine out of one hundred people took their arguments from the editorial and news columns of the daily press, today at least half of the voters sitting at their own firesides listen to the actual words of the political leaders on both sides and make their decision on what they hear rather than what they read.” Ned finds two things “telling about this statement. The first is the implication that the speech of politicians—this politician anyway—should be valued over the writing of newspapermen. The second is the invocation of the fireside as a place where you will not be manipulated by group pressure.” At present, with an autocratic president, manipulative Senate, politically slanted “news” channels, and a lack of attention to reliable evidence by which citizens might make sound judgments, this passage seems particularly relevant. Ned’s Facebook postings long ago convinced me that, on political and cultural issues, he was perhaps the most thoughtful and consistently reliable of all my Internet “friends,” and I counted on him for clear and rational reactions to current affairs. Perhaps his online posts were equivalent to a healthy fireside chat. Ned’s concluding chapters center on selections from E. B. White’s monthly column for Harper’s, collected in One Man’s Meat. His analysis of White’s essay about his visit to Walden is a shrewd piece of literary criticism, showing how White drew on Thoreau as an intellectual model but also diverged from him in life and outlook. Noting places where White gently and humorously identified both qualities they shared and qualities that distinguished them, Ned makes clear how White “broadened the range of his voice, experimented with the form of the essay, and wrote both more personally and more polemically [by] appropriating a form familiar to his readers—the fireside chat—and giving it new weight.” Ned ends his cautious, detailed literary history with a sharply balanced feat of literary interpretation. In a culminating examination of White’s essays, he reprints “a long tone-breaking two-sentence paragraph [from “Once More to the Lake”] that demonstrates the depth of White’s ambivalence toward his class and the attitudes that held it together.” White writes, in a paragraph that rewards reading out loud: Summertime, oh summertime, pattern of life indelible, the fade-proof lake, the woods unshatterable, the pasture with the sweetfern and the juniper forever and ever, summer without end; this was the background, and the life along the shore was the design, the cottages with their innocent and tranquil design, their tiny docks with the flagpole and the American flag floating against the white clouds in the blue sky, the little paths over the roots of the trees leading from camp to camp and the paths leading back to the outhouses and the can of lime for sprinkling, and at the souvenir counters at the store the miniature birch-bark canoes and the post cards that showed things looking a little better than they looked. This was the American family at play, escaping the city heat, wondering whether the newcomers in the camp at the head of the cove were “common” or “nice,” wondering whether it was true that the people who drove up for Sunday dinner at the farmhouse were turned away because there wasn’t enough chicken. In response Ned offers a richly observant reading of the paragraph, encapsulating both its lyricism and its complexity:

The range of the [first] sentence is stunning. It opens with a burst of purple prose, internal rhymes, apostrophic call to the past, and biblical echoes, and then moves through a spate of patriotic gushing, only to slam shut in a moment of uncompromising irony in which lime is sprinkled in a smelly outhouse and the store’s Americana grow smaller and smaller and phonier and phonier. Then, as a first-time reader tries to absorb all that this sentence serves up, the paragraph’s second sentence targets quickly, subtly, and clearly the way in which the privilege and bigotry of the middle class, White’s middle class, were cloaked in snobbish euphemisms that crippled all the parties involved. It is a shrewd, detailed reading, unlike any classroom anthology presentation of “Once More to the Lake” that I’ve ever come across. Having led us all carefully throughout the critical and political and cultural history of the essay in the decades leading up to One Man’s Meat, Ned compellingly demonstrates the validity of his approach. He concludes: “Returned to 1941, ‘Once More to the Lake’ opens up in new ways. It becomes larger and, as Lopate said, more ambitious. Might not the same be true of other American essays if they too were released from the first-year writing anthologies and read against history?” Given the propensity in academic circles of dismissing works of every kind because of a supposed lack of currency or “correctness,” Ned’s question deserves to be an animating question for new scholars: what happens when you read a work in light of the individual who wrote it and the times in which it was written? What happens when you read an essay from the perspective of the essayist?

In both my readings of The American Essay in the American Century, Ned convinces me that “if we want to explore the future of the essay, we will need to be thoroughly grounded in its past.” I’m grateful to have this book. I once hoped for a sequel exploring the changes in form and transmission and hybridization, the further evolution of the American essay. There are myriad reasons to mourn Ned’s passing; that Ned will not be here to write that sequel is simply one of them. |

Continue Reading...

|

|

|

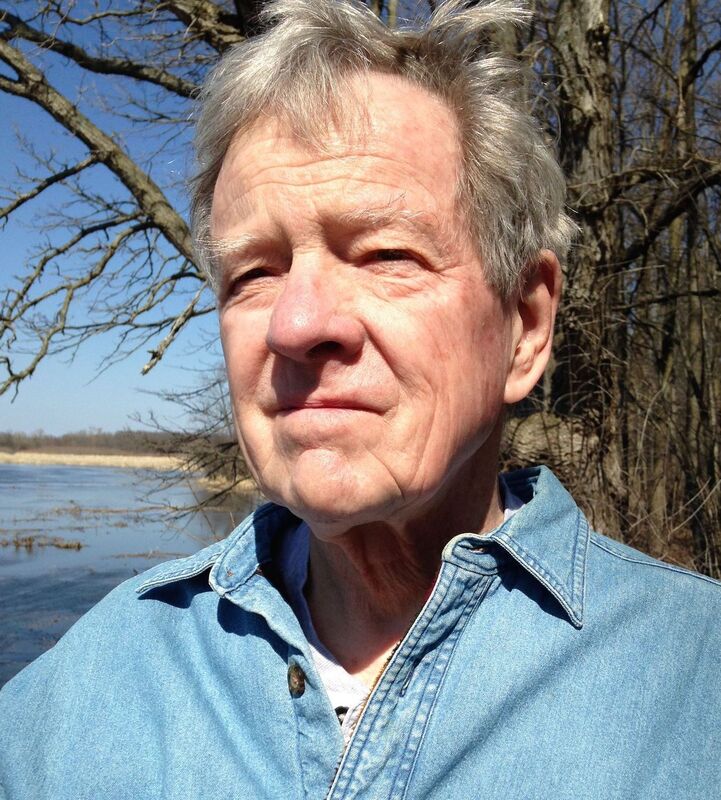

Robert Root is the author of the memoir Happenstance, the essay collection Postscripts: Retrospections on Time and Place, the craft book The Nonfictionist’s Guide: On Reading and Writing Nonfiction, and three narratives of place, most recently Walking Home Ground: In the Footsteps of Muir, Leopold, and Derleth. He co-edited The Fourth Genre: Contemporary Writers of/on Creative Nonfiction with Michael Steinberg and was Interview/Roundtable Editor for Fourth Genre: Explorations in Nonfiction. An emeritus professor of English at Central Michigan University, he teaches online for the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis and lives in Waukesha, Wisconsin. His website is www.rootwriting.com.

|