ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

10.1

10.1

|

Hervey Allen’s memoir Toward the Flame holds an important place in the legacy of the First World War and the book’s transformation to commemorative object with the release of the 1934 illustrated edition offers an even more nuanced discussion of its impact. The memoir, now rarely even mentioned in brief author bios of Allen, was first published in 1926 and reprinted during the interwar period in the illustrated edition on the coattails of the success of Allen’s novel Anthony Adverse; it became the standard edition for reprinting again in 1968 and 2003. The neglected nature of Toward the Flame academically and popularly is somewhat surprising given Allen’s success and fame in his own lifetime, winning a Yale Younger Poet’s Prize in 1921 and gaining fame with Anthony Adverse, adapted in 1936 to a Hollywood film of the same title. Allen’s 1927 biography of Poe, Israfel: the Life and Times of Edgar Allan Poe, influenced the American establishment of psychoanalytic studies of Poe, helping to situate Poe’s legacy more firmly in the American literary canon beyond his recognition at the time, primarily in Europe. And yet, this memoir remains in the shadows. Allen died early, in 1949, but it seems likely that the relative neglect and decline in popularity of Toward the Flame in the latter half of the 20th century is related to the declining interest in and changing collective memory of the war. Still, fiction from noncombatant writers like John Dos Passos and Ernest Hemingway persisted in popularity, despite their noncombatant status.

Toward the Flame’s tone and perspective, conscientiously straightforward with limited commentary either jingoistic or condemnatory and without a traditional narrative arc, leaves the first edition of the book a psychological artifact of the author rather than a commemorative object designed to reach out with a distinct position for readers or an exploitation of the horrors of war. The addition of Lyle Justis’s illustrations gives the book more appeal to readers beyond those who served in the conflict and transforms the book into a commemorative object of the war like those discussed in Steven Trout’s On the Battlefield of Memory: The First World War and American Remembrance, 1919-1941. The transformation is artistically similar to that which has become extraordinarily popular today in the graphic memoir; the personal narrative is transformed into something widely relatable via visual reference points. __________

As Steven Trout explains in the introduction to On the Battlefield of Memory: The First World War and American Remembrance, there is less currency in the contemporary collective memory of the first world war than in others, like Vietnam, World War II, and the American Civil War (1). The collective memory of all of these conflicts inspires continuous publishing, commemorative events and objects, and tourism both domestically and abroad, leaving questions about why the First World War is seemingly neglected in current collective memory, regardless of its being (by the numbers) the most memorialized war in American history (19-20). The war’s distinctly foreign locale, America’s first foreign war, may effect this neglect. And while also fought abroad, World War II has overshadowed the memory of World War I. The interwar period was one where commemorations to the First World War were still fervently, frequently taking place, as they arguably still do to this day. The understanding and memory of the First World War was then used as a scaffolding for understanding the project of the Second World War, a link so close perhaps as to overshadow the first conflict as mere precursor. World War I involved the mobilization of far fewer American men into a later stage of the conflict than World War II. Technological advances in the interwar period made World War II a vastly different experience in the dissemination of information both to the public and among the enlisted; a similar, if amplified, experience is associated with the media access of Vietnam as well. The battlefields of the American Civil War are obviously domestic and the conflict is directly linked to continuing contemporary civil rights struggles, making the conflict’s legacy difficult to ignore and maintaining its prominence in America’s everyday collective memory.

In the production of the illustrated war memoir, like Allen’s, the author’s personal memory and a new level of collective memory of war appealed most to those who had been part of the conflict and preferred to read about things just as they happened. Lyle Justis’s illustrations of Allen’s World War I scenes add a unique visual layer to the book as both interpreter of the text and first-hand witness of the conflict, a veteran of the conflict himself. Justis’s work elevates the existing memoir to commemorative object, appealing to a broader audience than only those who would have experienced the conflict close up. __________

Academic publications on Hervey Allen’s work in general are relatively scarce. With the recent centennial of the First World War, scholarly works which mention Allen and Toward the Flame are more plentiful, but only two focus on the scholarly, literary implications of the book. Keith Gandal’s 2018 book War Isn’t the Only Hell: A New Reading of World War I American Literature features a chapter which compares the impact of the voices Allen and Company K author William March chose for their narratives. Gandal discusses the books as “strangely silent on the issues and experiences of personal and social promotion, affirmation, and opportunity in the new army. This silence is odd since the authors both experienced such validation, and for both of them it is hard to believe that military validation was not meaningful” (200). By contrast, Travis L. Martin’s 2021 article “Reality and Anti-Reality in WWI and WWII Memoirs” discusses Allen’s Toward the Flame alongside memoirs by Robert Graves and Paul Fussell as writer-seekers of an “alternate-reality: Each author hopes to find meaning or at least consolation through constructing his tale-of-war” (1). What the memoir expresses and what purpose it fulfills still seem to be topics up for debate in the literature surrounding Toward the Flame.

The nature of the memoir as commemorative object is likewise open for debate. In a brief mention in his closing remarks to an issue of First World War Studies, Mark Whalan credits Trout’s 2003 edition of Toward the Flame as an expansion of the canon of World War I literature (284), an interesting notion for a book that was reprinted frequently in the 20th century. Whalan, like Trout, discusses the lack of consensus around the memorialization of the First World War in general (281); it is thus unsurprising that many cultural artifacts like Allen’s memoir are being reconsidered and added back into the literary-cultural cannon of a period which has never been particularly decisively set. Whalan discusses the dedication of the National World War I Memorial in April 2021, which he describes as “inclusive in ways that reflect the highly current (and charged) debate about the place of war memorials in broader US society, but is also deliberately noncommittal about the place of the First World War in the narrative of national history” (281). Indeed, understanding the uncertainty around commemorating war in our current society can help us to explain the relative neglect of many First World War texts. Edward Lengel’s recent accounting of American personal narratives of World War I also seems to reflect this sentiment: The experiences of American soldiers, uniformed noncombatants, and civilians on the Western Front in the First World War never fully entered the popular American consciousness. During and immediately after the war, American personal accounts mostly echoed official arguments that the United States had played a decisive military role on the Western Front. In the 1920’s and 1930’s a wave of more self-reflective accounts appeared, but a public preoccupied with the Great Depression largely ignored them. (1) History, we understand, never provided the conditions for proper reflection over the conflict, although Lengel is more positive on the progress that digital media has helped to generate since the 1990’s. He continues to outline distinct eras of personal accounts of the war, including “Early Accounts, 1918-1929,” where he places Allen as an exception to the rule of the era’s mostly triumphal and patriotic personal narratives (2-3). He characterizes Toward the Flame as having “…anticipated soon-to-be-published works by European authors such as Edmund Blunden…Siegfried Sassoon…and Erich Maria Remarque” (Lengel 3).

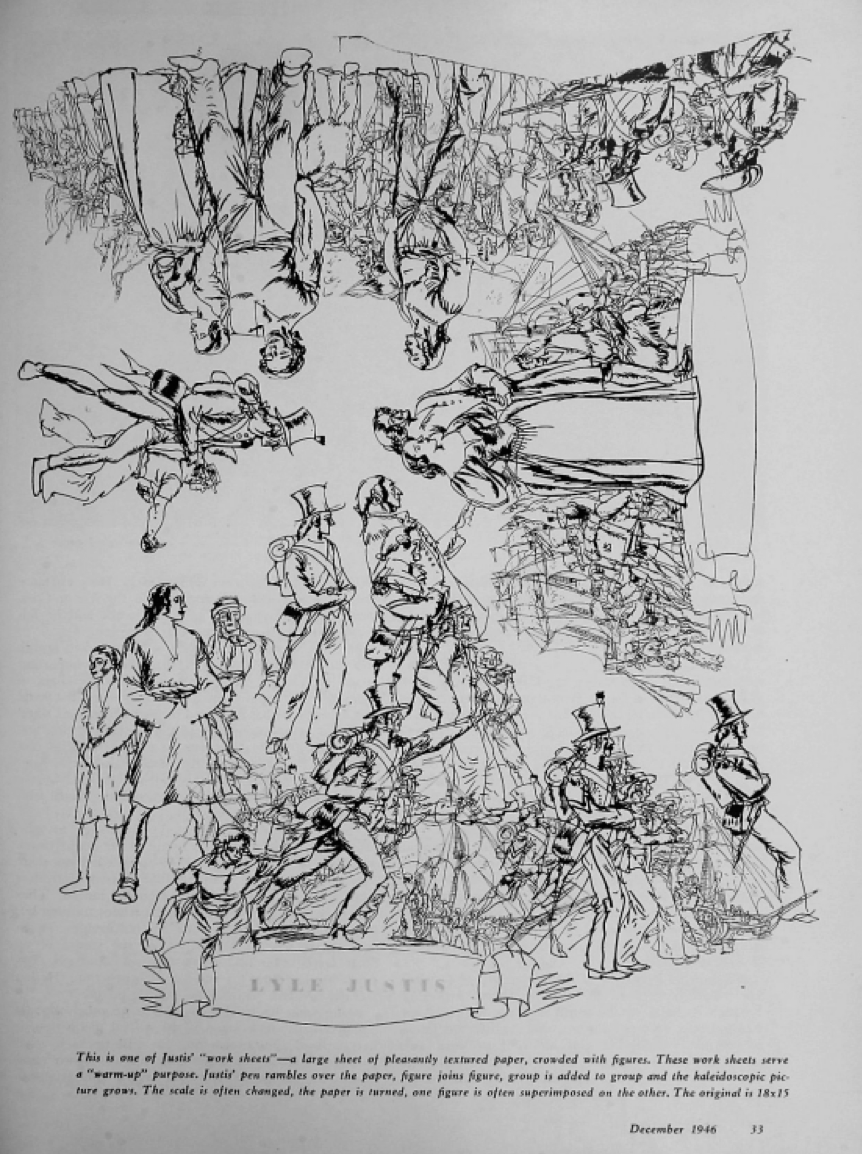

Precious little information, academic or otherwise, remains readily accessible about Lyle Justis, although the storybooks and novels containing his illustrations are still easily found. Personal blog posts from fellow illustrators in recent decades mention him but few electronically archived sources exist. An article from the December 1946 issue of American Artist by Henry C. Pitz gives a general overview of Justis’s early life and career in the eastern U.S., along with some discussion of his style and work to that date. Pitz’s article describes Justis as an illustrator who embodies a masculine American spirit, seemingly due to his body of work illustrating texts on classic American themes and his military service: “the core of his work is the pageant of America. He crowds his pictures with the multitude of types that America has shaped: pirates and peddlars, doughboys and G.I,’s, veterans of the Continental line, and Mississippi gamblers…this is a masculine world of Justis'” (31). The article contains no direct quotations from Justis himself; we must interpret Pitz’s decidedly vintage point of view of Justis’s attitude and work through the images included in the article and his colorful, patriotic, and romantic characterization of the illustrator. Interestingly, Pitz mentions that Justis finished formal education at eighth grade and that “After the [First World W]ar…He was given a Scholarship to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts” but left after the first day, finding the curriculum too rigid and confining (34). Pitz further explains that Justis, as an illustrator, was legitimately self-taught, as opposed to merely formally untrained (34). Another of the scant mentions of Justis can be found on the Delaware Art Museum website: “Edgar Lyle Justis was a book and magazine illustrator…Justis additionally worked as an advertising artist for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, United Artists, and various department stores…A veteran of the first World War, Justis was also known to teach drawing classes for fellow veterans at Valley Forge Hospital (“Lyle Justis”).” __________

Allen’s goal for his memoir is to craft a concrete reality which affirms the soldiers’ (and his own) truth without judgment; interestingly, Allen’s method has been mentioned and affirmed by contemporary researchers (Cigrang and Peterson 144). Doing more than this, condemning or condoning the war, would take Allen outside of this purpose. What may, in the presence of further commentary, be interpreted as heroic resilience in the men is thus able to be accurately observed and reported by Allen as dissociation and deep trauma. Readers are left to draw our own conclusions, condemnations, and feelings of heroic inspiration from his objective, experiential accounts. Allen’s memoir does move “toward the flame,” in the sense that slowly paced, daily motions of soldiers that make up the majority of the text eventually culminate in the gruesome debacle of the occupation of Fismette. Even within the telling of most of that episode, Allen is remarkably staid. It is only in the last few paragraphs of the last chapter that the text barrels “toward the flame” and we get the most direct passage in the book:

Suddenly along the top of the hill there was a puff, a rolling cloud of smoke, and then a great burst of dirty, yellow flame. By its glare I could see Gerald standing halfway up the hill with his pistol drawn. It was…the flame throwers; the men along the crest curled up like leaves to save themselves as the flame and smoke rolled clear over them. There was another flash between the houses. One of the men stood up, turning around outlined against the flame—'Oh! my God!’ he cried. ‘Oh! God!’ (Allen 277) The soldier is “outlined against the flame” and cries out, but his likely gruesome death or maiming is not actually described by Allen. This vision of the flame is the very last of the book’s narrative. Beneath this passage in italics is a sort of benediction (or, perhaps, malediction) akin to the language of a church service which reads: “Here ends this narrative” (Allen 277). Allen discusses the ending of his combat experience as the appropriate end for his narrative in the Preface to the 1934 edition: “If I did not inflict upon my readers certain personal sufferings and physical indignities that followed, it was because I felt that they were important to me alone. In other words, I meant this to be a report of what I saw on the battle line, and when the fighting ends the story stops” (x-xi).

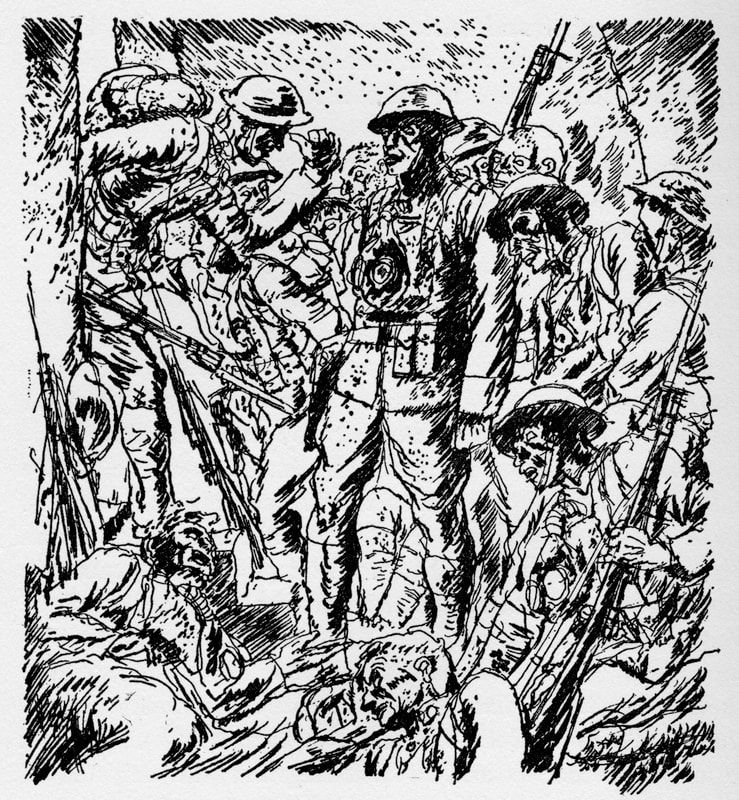

This choice of stopping right at the moment of highest trauma is an interesting and deliberate one. Some of the book’s plain language and matter-of-factness might suggest that Allen is dissociating. The final passage suggests that he is trying to describe the culminating events in a way that reflects a tendency for the men as people in on-going traumatic experiences to dissociate as a survival mechanism or a learned coping mechanism. Allen does not shy away from shellshock in the text, and the language he uses to describe it is telling. He confirms its existence, as opposed to its being something that can be explained away by doctors, as was common during World War I. The explicit witnessing and confirmation of the deep, traumatic responses of others is telling of one of the book’s main purposes. Unlike the dissociation that becomes natural coping to some soldiers, “shellshock,” or posttraumatic stress disorder, is an overstimulation response to the same experiences. If the ending marks a most important moment of change for the author, what, then, can we make of the rest of the text and what Allen remembers before this moment of change? There is camaraderie, reality, a verbal rendering of the ordinary moments of duty that march toward the vortex of seemingly inevitable tragedy. All that comes before that moment might feel to a reader to be so much trivia about the day-to-day soldiering of the war. The book is not really even about relationships between the men. It is just basic, true accounting for things. As Allen modestly explains in the “Preface” to the first edition, “It gives a glimpse of some of the fighting about Chateau-Thierry and Fismes, but above all, it shows how we lived and died, ate, cooked, looked, thought and felt during that time. It is the intimate detail of life at the front as I saw it, and pretends to be nothing more” (vii-viii). The closing addenda speak to the need on Allen’s part to express the absolute facts of what happened at Fismette, accounting for influences and reactions outside of the experiences he recounts. Allen includes them to give “A more general and official view of the fighting” from “some of the generals in charge of the operations” (xi). Memoir, with attendant narrative elements, can indeed often resist absolute fact and instead bring forth a one-sided truth for the author. The addenda reinforce the perception that Allen is resistant to taking a stance against the war, against the military, nor for anything. He is attempting as much as possible to demonstrate a factual account, even allowing for the points of view of commanders to clarify and possibly influence readers’ perceptions of the circumstances of the final tragedy. Fismette was already an unusual situation in the typically trench war. We might read that the legacy of the tragedy at Fismette is thus all the greater offered when accompanied by the addenda which demonstrate how the events came to transpire and were remembered in their immediate aftermath by superiors. Allen’s own statement in the 1934 preface about his specific intent for writing the memoir and to make it “objective in writing,” is certainly akin to modern exposure therapy for PTSD when true exposure is impossible (indeed, this passage is quoted in the recent article on exposure therapy by Cigrang and Peterson, 144). As Allen describes, the project was initially, primarily a therapeutic exercise, forsaking the potential literary quality of the writing and narrative for speedy completion (xxiv). If Allen’s goal was the transmission of largely uninhibited memory, the collaborative project is meant to instill some of the missing, overtly emotional content to the project, thus allowing the text of the new illustrated edition to connect with a wider audience than the one which relates to the strictly day-to-day military experiences of the first edition. Justis’s renderings can be seen, from interpretation of other prefatory passages, to be added to return a certain artistic substance to a text which originated with a primarily practical function for the author. Allen writes of Justis’s addition to the book: In particular it is thought that the illustrations of Mr. Lyle Justis will not only help to bring home to the reader the reality of the scenes here described, but what is more difficult, serve to make evident the general spirit animating those Americans who participated in the great Allied offensive of the summer of 1918. The artist himself took part as a soldier in the events he depicts. He knows his types, his locale, and his atmosphere. His illustrations are therefore the result of imagination drawing upon genuine personal experience. (ix-x) Justis is, of course, an excellent fit to illustrate the book. Importantly, he preserves Allen’s original purposes via his own World War I combat experience. Justis’s visual content also amplifies the emotional tenor of the majority of the book which is otherwise rendered incredibly subtly on its own. Where Trout describes objects like E.M. Visquesney’s Spirit of the American Doughboy as “a visual tug-of-war between…accuracy and creative heightening—between vernacular realism and official idealization” (120), Justis’s experience in the war helps him to overcome the limitations of purely capitalist-driven production of visual material to actually bridge the gap between subjective experience and objective portrayal.

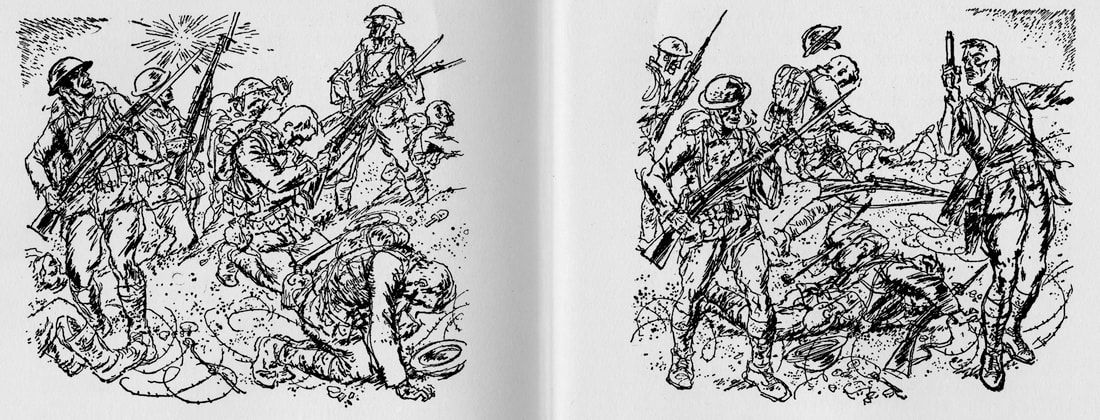

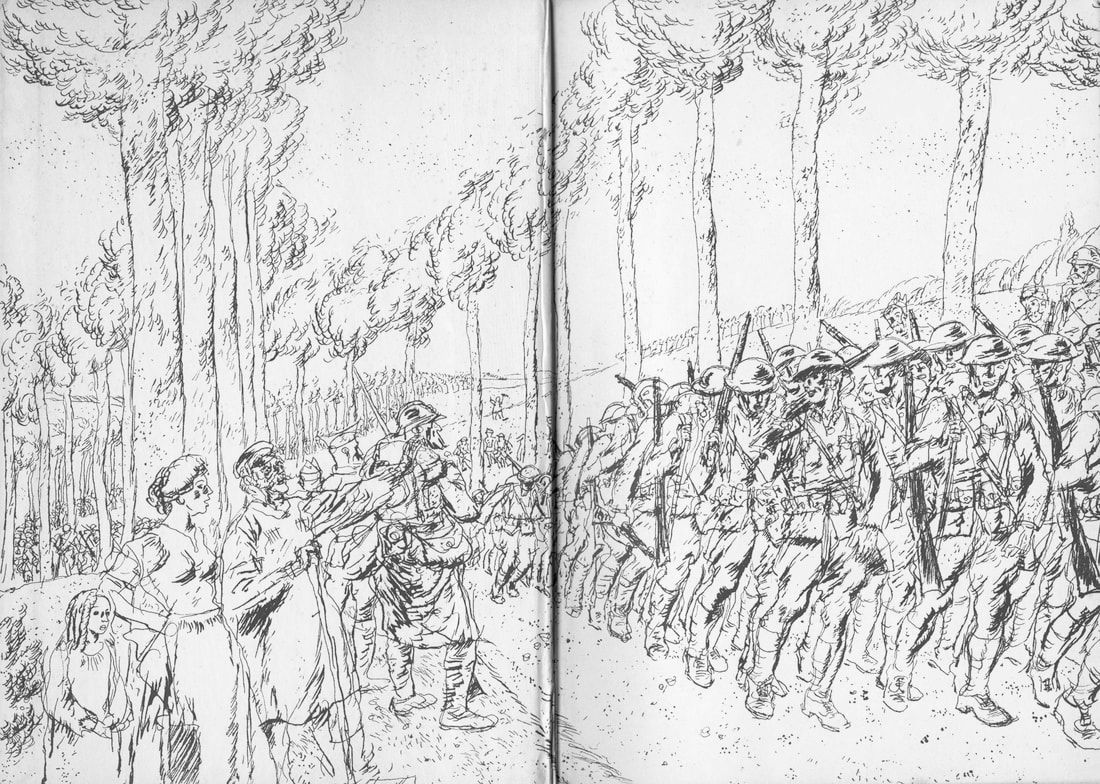

The book’s accompanying images reflect Justis’s typical, line-driven illustration style, but always emphasize the reality of the lives of the men and do not shy from expressing the brutality and death of the conflict. Rather than creating towering, heroic figures, the men’s faces toward the end often feature eyes that are so hollow as to look skeletal, suggesting the positioning of the men in a space constantly between life or death (270-271, 276). Throughout the book, the silhouetted figures are emphasized, seldom illustrated in full background, in vignettes and groups and simple portraits of individual figures. This matter-of-factness and intent focus on the men as they were matches the direct language that Allen uses. We can note a marked transition in the images’ tone from the beginning of the book to the end, reflecting the changes of the soldiers from ordinary men marching in the book’s front cover to a very small amount of living among the dead in the end. In the front cover image, we have a troupe of men marching through France, trees in rows alongside them, with both trees and men creating perspective and distance, and movement toward the foreground of the illustration. In the middle of the drawing, groups of men are just suggested by very simple lines, as are lines of trees in the distant background and, on the left side of the page, they blend in among the trees. The repetition of these trees in the background suggests a kinship between the lines of soldiers and the lines of trees, all of whom are living and vibrant. The men move toward the foreground of the picture while a group of a few civilians and officers to the left watch their progress. The older man among the civilians raises his left arm, which appears to offer acknowledgement or benediction toward the marchers; however, this arm is blended almost entirely into the form of the officer standing near him, rather than cutting across his front visually.

The marching men, while alive and filled with vitality and mostly pleasant expressions, betray small hints of the skeletal, hollow, and crumpled forms they will take by the end of the book. Justis’s line-driven style blends the men together into a monolith with repeated round helmets and dozens of feet in lockstep. One figure on the right side of the page stands at the visual fore and his expression drifts toward the left side of the page. Ambiguously rendered, his gaze may fall upon either the civilian woman, the somber little girl, or the ghostly old man, all of whom fall into his line of sight. Each of these figures might represent some different aspect of the soldier’s future, and their attitudes, particularly that of the old man, can be interpreted as curious or ominous. We may also see the civilians as a group conveying an innocent past, a lively present, and an ominous future. There is a certain flatness that is present here and in much of the book, in part a result of Justis’s reliance on drier crosshatching and stippling rather than employing a wetter-looking, bleeding ink: “He prefers chinese ink ground down from the stick, or in bottle or tube form. It has a tactile quality that is much more appealing than the shinier india ink, and its subtle shadings add immeasurably to the quality of his drawings” (Pitz 46). The images blend and layer rather than bleed or coalesce.

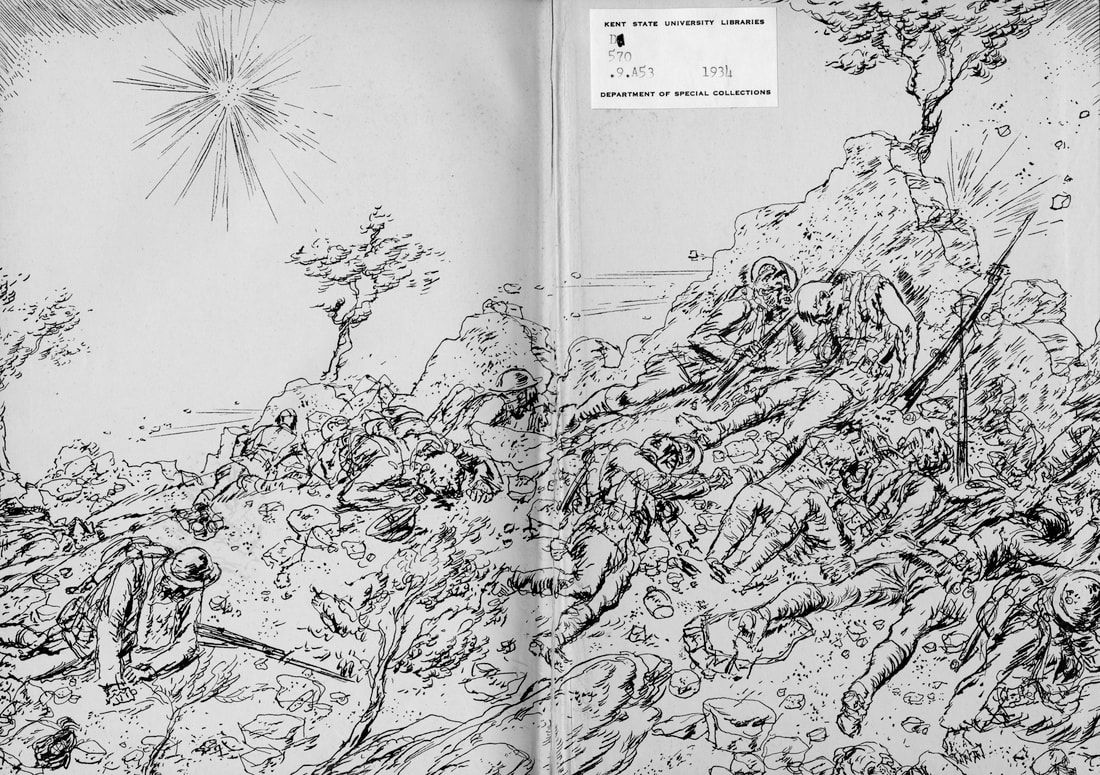

The back cover images exist in direct contrast, compositionally and in subject matter, with the images of the front cover. A similar organization of perspective is used, with the right side of the illustration occupying the most space in the foreground and the visual weight receding toward the left. Trees, which lined the front cover image in such numbers, are now only three left standing, with branches of one downed in the bottom left. A shell is bursting in the top left amid an empty sky, while a jagged line of ruined wall draws the eye from right to left and front to back, as in the front cover image. Short lines along the top of the remaining wall indicate shots still being fired on the men strewn about below the remaining fragments of wall. Among these signs of continued fire, it is difficult to tell which, if any, of the soldiers along the wall still live, and Allen’s narrative leads us to think this image is the moment before “the flame:” “Some one came and said, ‘They are all dead up there along the wall, lieutenant’” (277). Rather than blend into one another in a monolith as in the front cover image, now the soldiers blend into their surroundings, with their helmets, canteens, even faces and bodies barely distinguishable from the pieces of rubble around them. This effect is achieved in part by the lack of color in the illustration and the reliance on the contrast between lines and space. While we can reasonably imagine that some of the deeper, thicker lines are spilled blood, the lack of color and use of contrast again encourages a viewing where the men and earth are blended and ground down together. On the very left of the page, approximately one quarter of the way up from the bottom, we find an incredible example of this blending of men and rubble. At first glance, we may notice only rocks piled behind a soldier who appears to crawl. After close examination, and especially when the book is physically rotated toward the right, we can observe the clear profile of a man’s face: nose, eye, eyebrow, mouth, jaw, and ear all plainly expressed. After rotating the book back to its normal orientation, the thick line across the cheek and stippling around the eyebrow demonstrate clear similarity to the rubble surrounding the man. Justis’s preliminary sketches, or “work sheets” (Pitz 46), also demonstrate this shifting physical perspective in his practice, making what we see here a surprising and yet characteristic inclusion on the part of the illustrator.

The rendering of images of men dead or near death in the end confirms a reading of Toward the Flame, at least of the end, which is one of horror and death, even if Allen never specifically engages expressly with the position that the war is horrible and condemnable, as other famous World War I authors would shortly do (Lengel 3-4). Together, the horror that Allen does suggest is horror that Justis renders explicitly when illustrating. Justis’s illustrations create a collaborative object by fusing his own experiences with the memory-based material of the author, demonstrating a shared collective memory between two artists which forges the commemorative object. The illustrations are intended to widen the audience of the book. As Trout relates in the introduction to the 2003 edition, “Farrar & Rinehart’s decision to reissue Toward the Flame in a larger, more elegant format, complete with Lyle Justis’s evocative drawings, probably had as much to do with Allen’s sudden name recognition and marketability as it did with the respectable following that the original edition…had inspired among World War I veterans (xiv).” An illustrated edition of a book necessarily has an additional purpose and function beyond the memoir’s narrative. There is stark contrast between Pitz’s discussion of Justis’s experience in World War I as a solider and the horror and strife depicted in his illustrations for Toward the Flame. Writing and observing Justis in the victorious period immediately following the Second World War, there was likely little motivation on the part of either writer or interviewee to discuss the horrors of war with much accuracy. This attitude likely ties into the way war is remembered given the particular situation and audience, as demonstrated in Lengel’s review of American WWI personal accounts and memoirs and also on page xiii of Trout’s introduction to Toward the Flame. Perhaps this is another way of concluding that the interpretive nature of visual material does not or cannot always match with the experience of the artist when verbalized. Visual arts, including illustrations, while still subject to various interpretation, perhaps do not (or do not in the same way) absorb as much of the political feeling of the time the way a written text does. The differences from the front and back cover pieces also add a suggestion of narrative continuity that is a bit lost in the marching, detail-oriented objective report of the memoir. The first and second editions of the book straddle the time periods which Lengel lays out, thus illustrations might have a transformative effect which bridges this time period in addition to or even necessarily for its (co)transformation to commemorative object.

Trout discusses physical monuments throughout On the Battlefield of Memory. Like Whalan, Trout discusses in the introduction how monolithically-scaled monuments to World War I had an unusual difficulty coming to fruition, largely due to differences in opinion over legacy. The largest monument to the war, still to date, is the Liberty Monument in Kansas City, which was completed the same year as the publication of Toward the Flame. He describes it as having “overtly celebratory and idealistic commemoration, achieved through a combination of artistic elements” (21-22). While the combinatory effect is not a mandatory quality for commemoration, Trout does explain that it was a fashion at the time to combine elements to create this effect. The appearance of the local Spirit of the American Doughboy statues and their subsequent downscaling into household items like lamps and desktop trophies speaks to mass production culture. The book as an object has always had a tendency toward the mass market, even when historically it was difficult or expensive to manufacture and distribute. Books are objects of collective memory and extensions of collective experience, like those Doughboy figurines turned into household objects. And while private, a household-sized commemorative object is still something that one can interpret as they wish and in different manners over time, falling well in line with the goal of Allen’s neutrally-positioned memoir. It is the “elegant format, complete with Lyle Justis’s evocative drawings” (Trout xiv) that makes the book quite literally more than just reading material. It is a collective work of more than one experience of the war which invites multiple interpretations and remembrances as well. Regardless of the motivations; artistic, capitalist, or both; the book acquires a commemorative state with the addition of the illustrations. Allen’s trajectory “toward the flame” is a path toward his culminating traumatic moment, a trauma that he felt did not need to be explicitly symptomatically described as much as spoken for itself through objective writing. The illustrations of the ordinary movements and lives of the men seem to foreshadow the death and destruction of the end passages, even from the book’s opening cover image. They also contribute to the emotional weight of the book while maintaining the distance from explicit protest that Allen’s language seeks to avoid, fearing that such language might obscure the tangible in a way the illustrations do not. Justis’s images do lend to a depiction of the horror of the situation in a direct way. This collaborative combination of elements leads to the production of the commemorative object, at once more saleable and necessarily encompassing more of the lived experience of war for more readers. The aesthetic and cultural legacies of Allen, Justis, and other First World War books of the variety once popular and now seldom read shed some light on what shape the legacy of the war took, especially as absent as it feels in contemporary life. |

|

Anne Garwig graduated from the NEOMFA and is currently a doctoral teaching fellow in literature at Kent State University. Anne's poetry has appeared in Abstract Magazine, Cleaver, TIMBER, The Mojave River Review, The Ekphrastic Review, and Jenny. Her dissertation research discusses queer Modernism and its attendant formal innovation. She also writes about visual culture and art.

|