ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

7.1

7.1

|

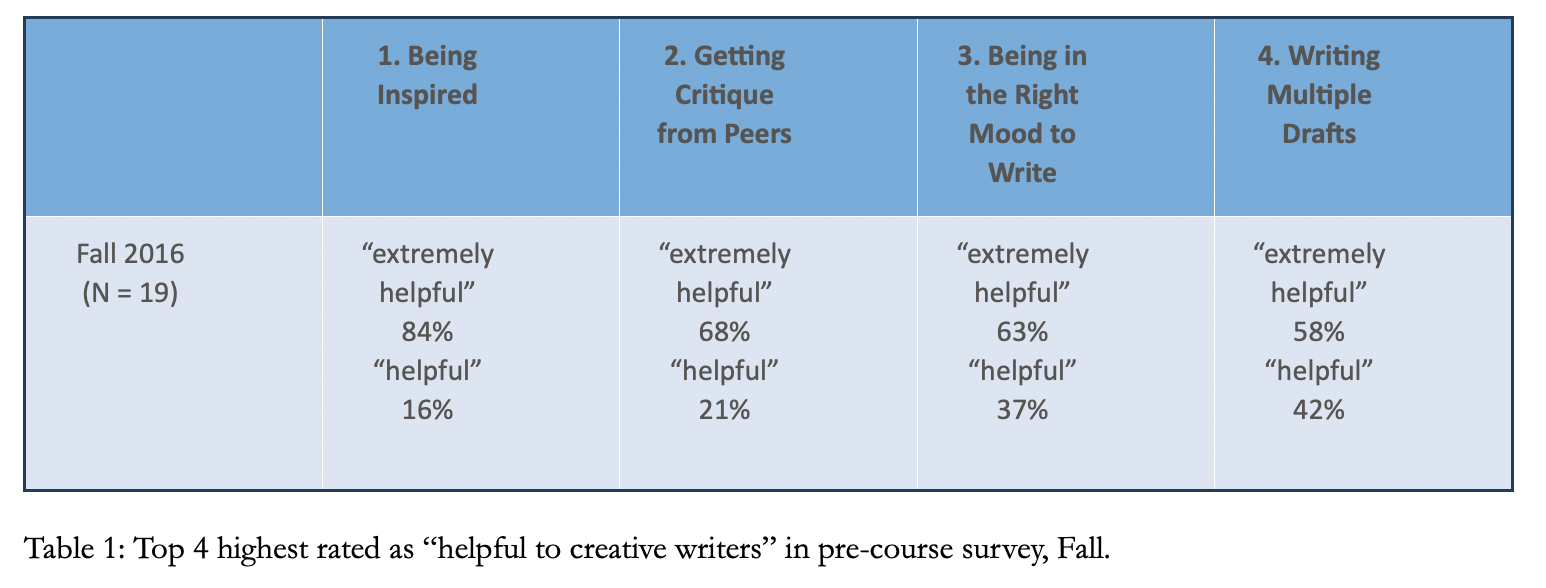

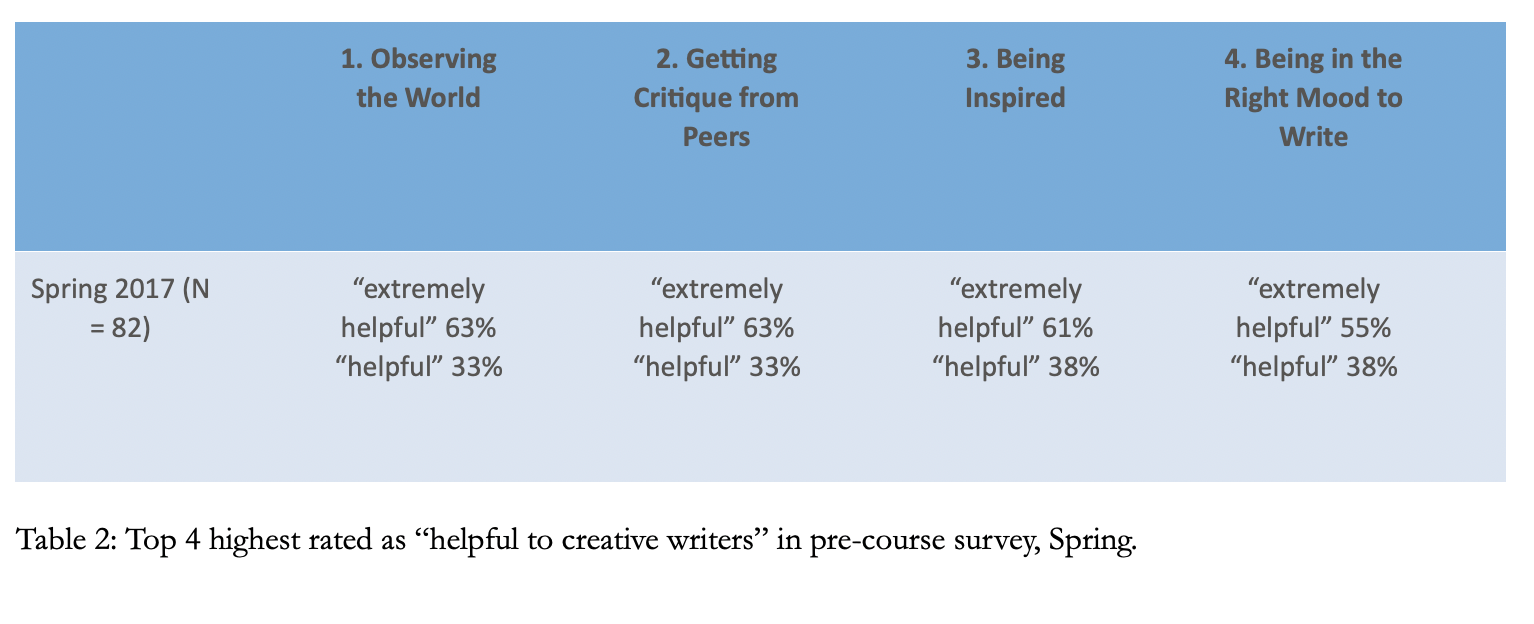

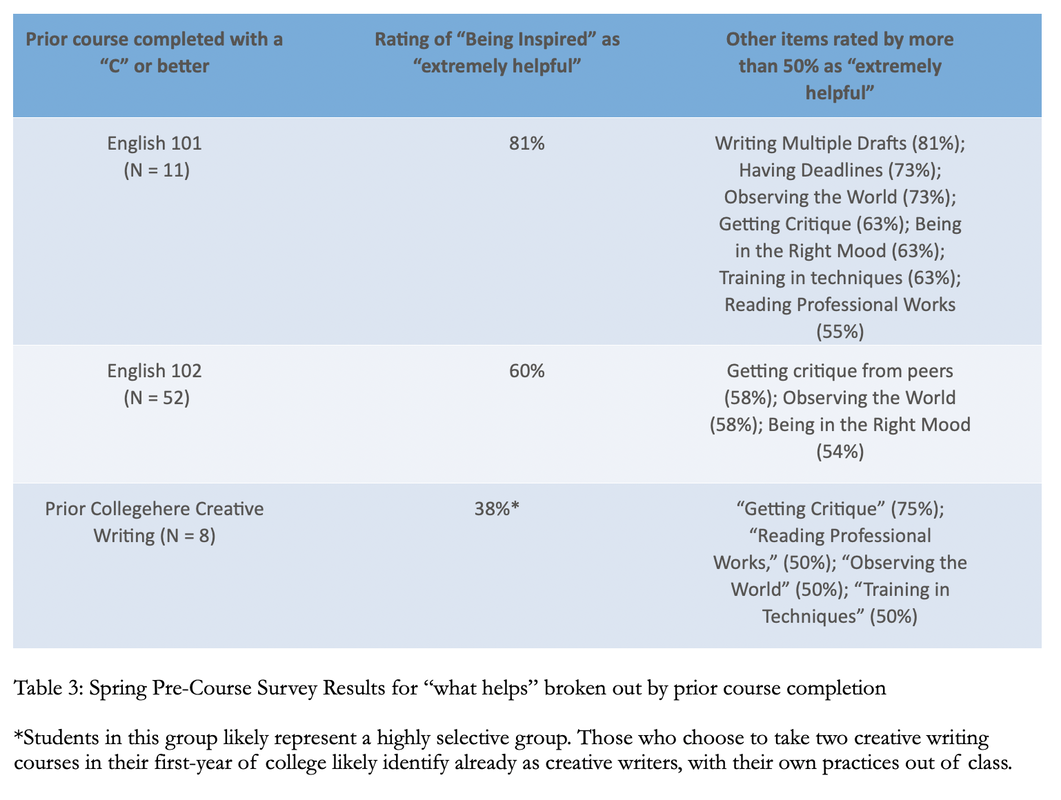

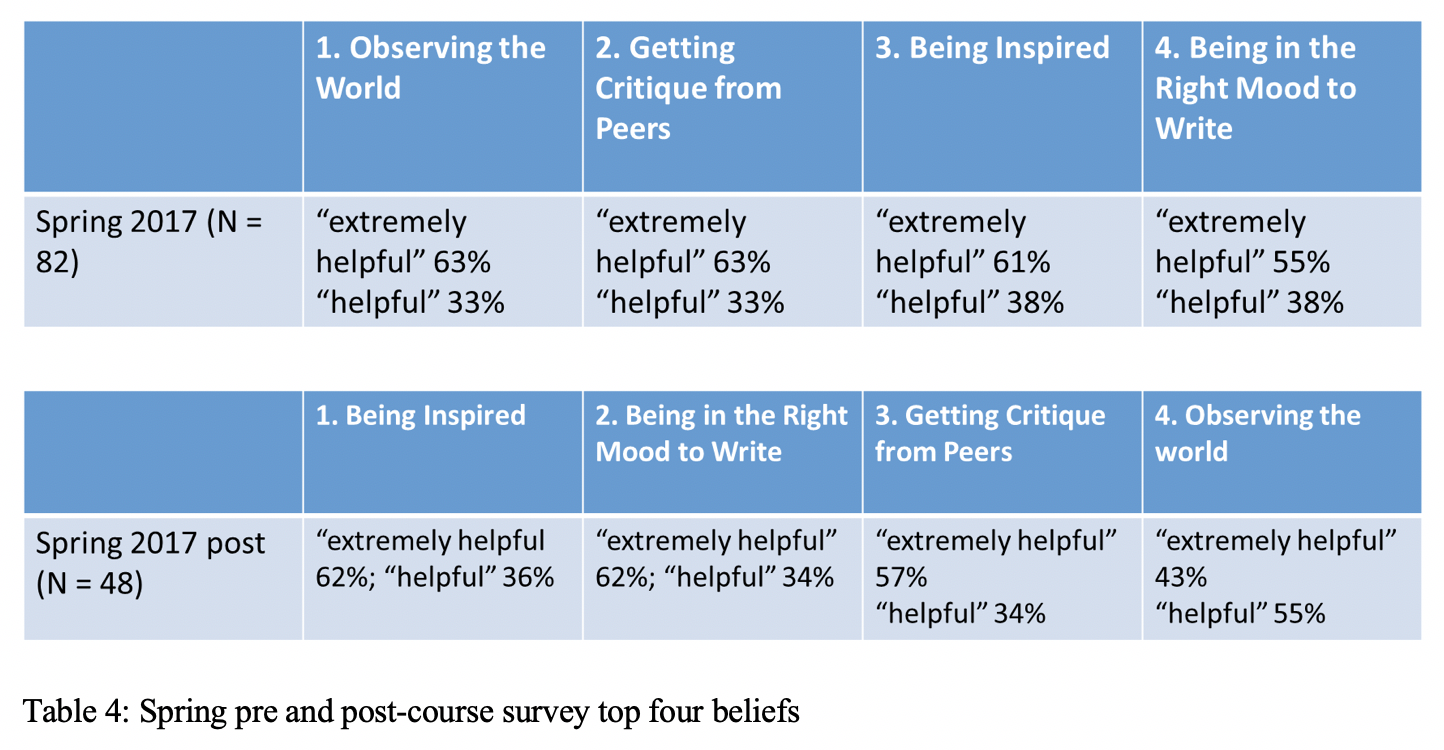

Wendy Bishop claimed that “…generation is the first requirement of a writing process” (62). Yet for many novices, learning that writers do something other than pull lucky lightning bolts down from the sky first requires a paradigm shift. Luckily for writing teachers, identifying such points where our students need to shift their understanding—the threshold concepts of our disciplines—helps us to design powerful learning activities. In the following, I report on a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning project (SoTL) conducted in Introduction to Creative Writing at a two-year college in which I gathered and analyzed evidence of an activity—keeping a collaborative journal of observations—designed to help students unlearn myths of inspiration and shift attitudes about the writing process. The results show that students do indeed enter Creative Writing with powerful prior beliefs about the role of inspiration in the writing process; further, transfer of knowledge from first-year composition and creative nonfiction writing assignments aid them in their learning about generation.

In their collection Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts in Writing Studies, editors Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle identify “writing is a knowledge-making activity” as a fundamental principle for the field. In the collection, Heidi Estrem further explores the concept, elucidating that writers discover what they know through writing—disciplinary knowledge that creative writers certainly co-own. Yet, novices tend to regard writing a poem as a task of transcribing an idea or feeling already fully formed, impeding their entrance to the deep practice of the discipline. Additionally, new creative writers have another problem when it comes to “inspiration.” Many believe creativity itself is an inborn trait—a belief that can be shared when it helps them but function as a weight when it does not. University of Maryland researchers Denis Dumas and Kevin N. Dunbar find in “The Creative Stereotype Effect” the mindset that one is creative (or not) to be a factor of success in divergent thinking tasks, a measure for thinking creatively. Given this, it might seem we should coach all students to believe in their innate powers of creativity. The research echoes an insight plumbed by James Tate’s poem “Teaching the Ape to Write Poems,” in which the sole pedagogical move is Dr. Bluespire’s prompt “’You look like a god sitting there. / Why don’t you try writing something?’” Yet for students to gain true disciplinary understanding—to learn how writers actually work and regard their craft—we can’t trick them all into believing, all of the time, that they are gods, possessed with the power of creation. Myths of the solitary genius writer not only set up an unattainable standard (all too easy for one rejection to deflate) but are especially deleterious for creating an inclusive curriculum. In Toward an Inclusive Creative Writing: Threshold Concepts to Guide the Literary Writing Curriculum, Janelle Adsit points out the particular difficulty for students from some marginalized communities to identify with the solitary writer who can choose to sit outside (and above) their community, leisurely awaiting the muse. Thus that creativity can be taught and practiced, that writers use a variety of strategies to jumpstart their work, becomes to key to an inclusive curriculum, in addition to a more practical one—and possibly a more transferable one. According to Adler-Kassner and Wardle, curriculums based on threshold concepts, because of how they provide students with a metacognitive framework to contextualize their learning, work hand in hand with the goal of teaching for transfer. When designing a project to help students unlearn reliance on inspiration, I was also interested in another habit of mind of writers: observing, or what Rebecca Meacham calls “learning to see anew.” “Learning to see anew” refers to writers developing their eyes and ears for details and encompasses a writerly approach to the world in which the writing process is understood to begin away from the writing desk and instead to suffuse the writer’s everyday life. Many writing teachers assign journals to help students learn to observe and to generate, mining their lives for material. I hit upon the idea of keeping a collaborative journal of observations on a google doc (accessible on phones, when out in the world) in order to open discussion of what makes interesting observations and how writers, in different ways, might reuse such details later. This activity would prompt students to both practice and reflect upon “seeing anew” and help them reconceive received ideas of “inspiration,” replacing them with a notion of writers at work in the world. The focusing research question for my SoTL project became: “How might direct instruction in keeping a journal of observations influence introductory creative writing students’ attitudes about how creative writers generate material?”

|

|

Jill Stukenberg is an Associate Professor of English at University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point at Wausau. Her pedagogical work has appeared in Arts & Humanities in Higher Education and Teaching English in the Two-Year College, and her creative work in The Collagist, Midwestern Gothic, Wisconsin People & Ideas magazine and elsewhere. She earned an MFA from New Mexico State University and has taught first-year writing, developmental writing, and creative writing at community and two-year colleges in multiple states.

|