ASSAY: A JOURNAL OF NONFICTION STUDIES

6.1

6.1

IntroductionThe phrase “creative writing studies” appeared in the 2009 special issue of College English dedicated to exploring creative writing at the college level. In his article, “One Simple Word: From Creative Writing to Creative Writing Studies,” Timothy Mayers differentiates creative writing from creative writing studies by describing creative writing as “the academic enterprise of hiring successful writers to teach college-level creative writing courses,” and creative writing studies as “a field of scholarly inquiry and research that has three main strands: pedagogical, historical, and advocacy-oriented” (Mayers 218). According to Mayers, creative writing studies embraces theory and interdisciplinary collaboration, especially in connection with composition studies. Mayers also suggests that creative writing studies can offer a break from workshop pedagogy in the creative writing classroom, for, as scholars like Joseph Moxley and Wendy Bishop asserted before him, workshop pedagogy is neither the best, nor is it the only teaching practice available for the course.

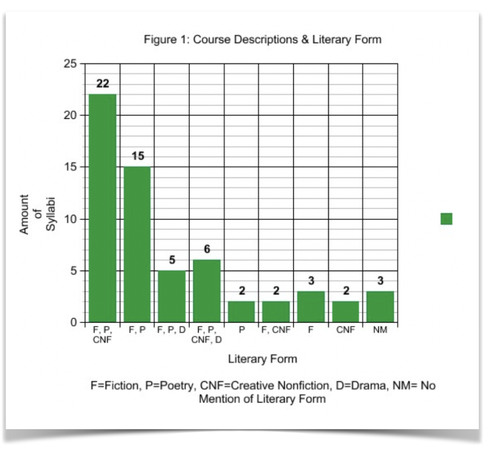

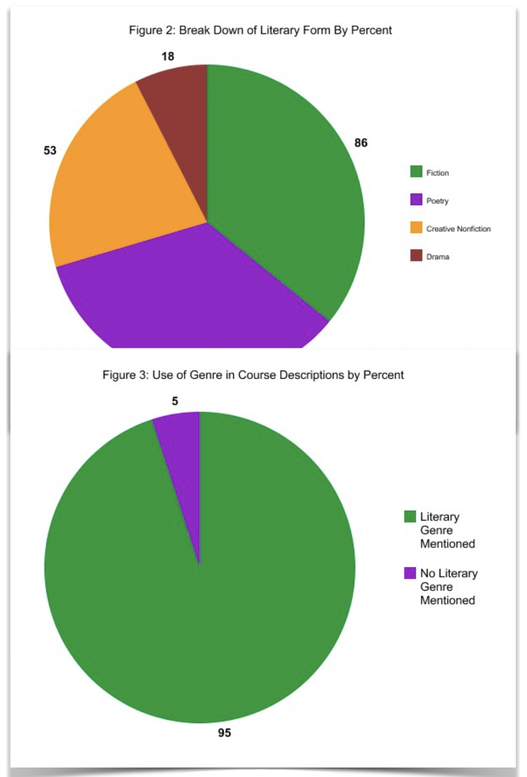

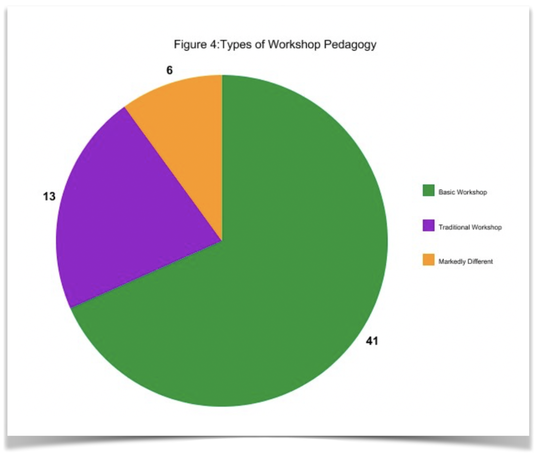

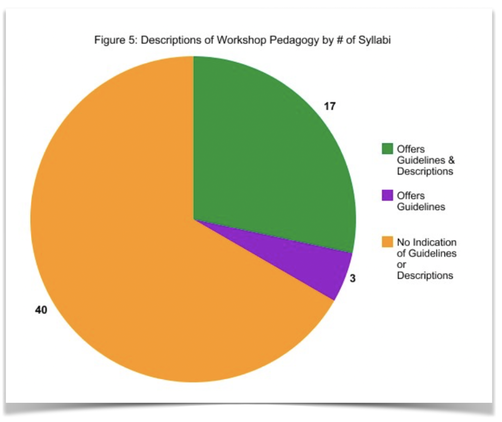

Within the margins of the “Comments & Responses” section of the preceding issue of College English, Anna Leahy and Catherine Brady expressed fears that “One Simple Word” misrepresented the creative writing at the college level, and their concerns sparked a continuing discussion on traditions and pedagogies associated with creative writing and creative writing programs. Decades ago, a popular debate surrounding creative writing pedagogy was whether or not writing could be taught. Some instructors thought (and still think) that a writer is born a writer. In some ways, that argument has fallen out of fashion, and the new style of questioning probes not whether writing can be taught, but how instructors go about teaching it. “One Simple Word” claimed that workshop pedagogy dominated creative writing courses; Catherine Brady alleged otherwise. If conversations on the craft and teaching of creative writing have evolved so tremendously over the past decade, how has our teaching represented these changes? Current conversations surrounding creative writing studies appeal to interdisciplinary, multimodal, and multigenre teaching methods and student outcomes. Adam Koehler advocates for a stronger incorporation of the digital humanities, Timothy Mayers pushes against the anti-intellectual identity of creative writing courses, and Anna Leahy promotes the possibilities of fashioning a department comprised of individual scholars from different fields—neurology, psychology, fashion, linguistics, and so on. These new theories suggest that creative writing is welcome to multiple pedagogies. Do introduction to creative writing course syllabi work in tandem with the most recent scholarship? In pursuit of an answer to the question of how students are introduced to creative writing at the college level, I investigated sixty introduction to creative writing syllabi from across the nation. In closely examining these syllabi, I looked to determine popular and/or alternative pedagogies, reading assignments, writing assignments, and assessment guidelines. My research confirmed that workshop pedagogy is the most popular form of teaching creative writing, with influences of its structure appearing in 60 out of 60 introduction to creative writing syllabi. A hegemony exists when dominant features permeate a sense of authority and rightfulness, not by means of research by but means of persuasion. Operating as a hegemony, the workshop tradition controls creative writing pedagogy. Instructors and students have been convinced of the workshop’s power because that is the way they were taught. However, out of all of the classes offered in Liberal Arts, the introduction to creative writing course has the flexibility to move across disciplines, employ multiple forms of media, and offer a variety of processes towards writing. bell hooks’s theory of counterhegemonic practices conceded that in order for new ideas to happen, new spaces need to open for those ideas to live. Sticking oneself in the same place every day will create the same outcomes. The growth of creative writing at the college level is associated with the counterhegemonic theories and protests of the 1960’s and early 1970’s: antiwar demonstrations, the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, civil rights protests, and the Second Wave women’s movement—all socially imperative moments that have altered the course of the American education system. In addition to the foundation of the Creative Writing Studies Organization, have contemporary movements like #MeToo or #BlackLivesMatter prompted us to reconsider about how we introduce creative writing to our students?

|

Click here to download a printable PDF with Works Cited.

|

Born and raised in Brooklyn, New York, Abriana Jetté is a writer, educator, and editor. She writes a quarterly column on poetry for Stay Thirsty Magazine, and her work has appeared in dozens of journals including PLUME Poetry Journal, The Seneca Review, The Moth, and others. Currently, she lives in New Jersey, where she is a Lecturer in Writing Studies at Kean University.

|