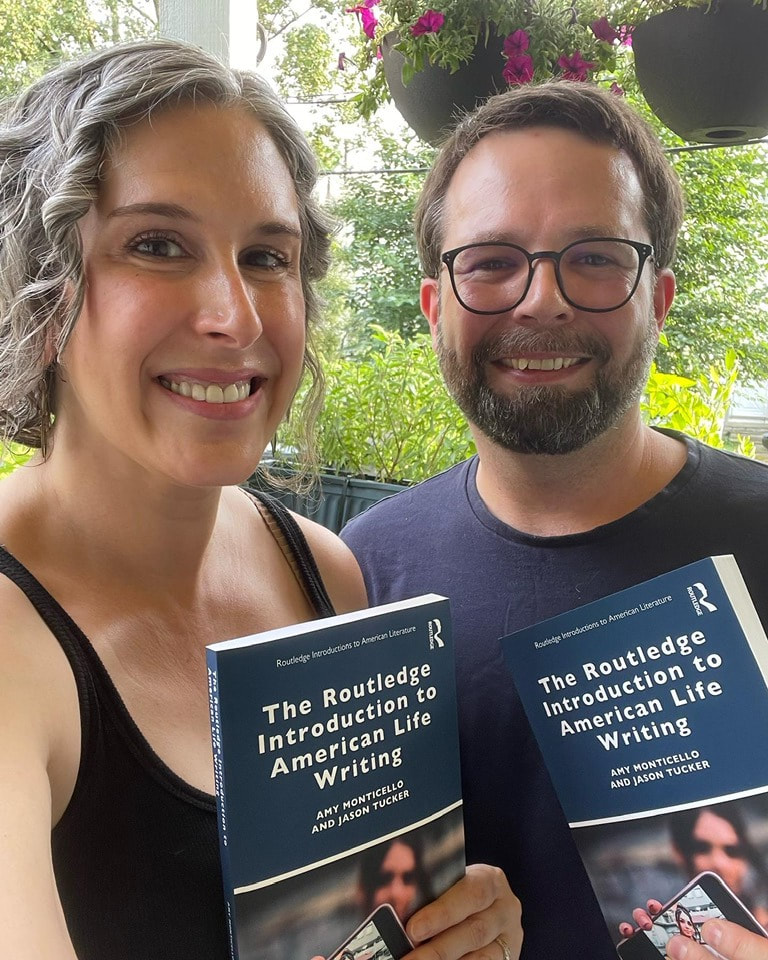

The Assay Interview Project: Amy Monticello & Jason Tucker

October 1, 2023

|

Amy Monticello is the author of Close Quarters, a chapbook memoir about unconventional divorce (Sweet Publications, 2012), and the essay collection How to Euthanize a Horse, which won the 2016 Arcadia Press Chapbook Prize in Nonfiction. Her work has been published in literary journals such as the Los Angeles Review of Books, Creative Nonfiction, Brevity, under the gum tree, The Iron Horse Literary Review, Hotel Amerika, CALYX, and The Rumpus; featured on Salon, The Establishment, Everyday Feminism, Quiet Revolution, and other popular websites; anthologized in Going Om: Real-Life Stories On and Off the Yoga Mat; and listed as notable in Best American Essays. She is an associate professor at Suffolk University.

Jason Tucker is an instructor of English at Suffolk University in Boston, MA. His essays have appeared in The Southeast Review, River Teeth, Cream City Review, Sweet, Waccamaw, Writer's Chronicle, and elsewhere. |

|

About The Routledge Introduction to American Life Writing: The stories of lived experience offer powerful representations of a nation’s complex and often fractured identity. Personal narratives have taken many forms in American literature. From the letters and journals of the famous and the lesser known to the memoirs of former slaves to hit true crime podcasts to lyric essays to the curated archives we keep on social media, life writing has been a tool of both the influential and the disenfranchised to spark cultural and political evolution, to help define the larger identity of the nation, and to claim a sense of belonging within it. Taken together, individual stories of real American lives weave a tapestry of history, humanity, and art while raising questions about the veracity of memory and the slippery nature of truth. This volume surveys the forms of life writing that have contributed to the richness of American literature and shaped American discourse. It examines life writing as a rhetorical tool for social change and explores how technological advancement has allowed ordinary Americans to chronicle and share their lives with others.

Heidi Czerwiec: Amy and Jason, I’m so excited by this new guidebook you’ve edited, The Routledge Introduction to American Life Writing. I want to take this opportunity to talk more about your process of assembling this text, from recognizing a need, pitching the idea, curating the contents, and marketing the final book.

This text seems to have taken Karen Babine’s LitHub essay “A Taxonomy of Nonfiction; Or the Pleasures of Precision” and run with it, reiterating the classification system Babine proposes as it applies to “life writing,” and filling it in, in detail. It names the big forms that comprise the genre of life writing in America—personal essays, memoir/autobiography, literary journalism, lyric essays, diaries/epistles/speeches, aural narratives, and life writing online—and then fills in the main subgenres of each: for instance, memoir subdivides into grief memoir, parenting memoir, travel memoir, etc. It also describes the dominant shapes or modes used by each form and subgenre, from straightforward narratives to nonlinear lyric braids, giving examples at each level, and going into deeper analysis of some. It’s comprehensive and thoughtful, and it’s invaluable to the literary and nonfiction communities to have this kind of framing. Fiction has James Woods’ How Fiction Works and Mieke Bal’s Narratology; poetry has Fussell’s Poetic Meter & Poetic Form and The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. We currently don’t have a foundational overview of CNF that could be used by both the literature and creative writing disciplines—most are craft texts that focus more on how-to and/or anthologies. A lot of us recognize holes in the available materials, but not all of us are willing or able to put in the work necessary to produce a text like this, and I’m so grateful to the two of you. To begin, what was the instigating moment for you? What need do you see this text fulfilling? Or, asked another way, in what ways do you see this guidebook providing an option that wasn’t previously available? AM&JT: Those craft texts are all built on deeper philosophies of how CNF works, and many of them do include brief analyses, but they are written for other writers to develop their craft. We found that there is a lot of scholarship on CNF texts, but it tends to focus on individual forms (like the essay or memoir) or subgenres (like true crime or addiction memoir), rather than looking for patterns common across all of those categorizations. Those are about depth. To find the breadth you’d expect from an introductory overview, we collected voices from a range of different literary specializations that otherwise might not have been speaking so directly to each other. We both come from a craft-focused, CNF-writer background, but our other influences from rhetoric and composition gave us ways of considering how CNF writers across all these different categories told true life stories in order to define and create themselves, their communities, their country. The biggest unifying thing we found in writing this introduction is that life writing is an act of democracy. HC: That’s interesting, life writing as “an act of democracy”—could you say a bit more about how you see this relating specifically to your focus on American life writing? AM&JT: America has produced privileged writers from dominant castes who held themselves up as examples of some singularly true or ideal American. Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography is an example. American life writing is far more filled with those who told their own life stories in order to democratize, in order to resist their own erasure and any narrow view of Americanness, in order to write themselves into the national story as they were already living it. HC: How did you decide what illustrative examples to use, and to delve more deeply into? AM&JT: Some canonical figures like Benjamin Franklin and Frederick Douglass have been so influential and representative of their times as to be unignorable in an overview like this. Others like Melissa Febos and Leslie Jamison have written such insightful essays about life writing that they shaped how we saw the project ourselves. Some writers we saw as being typical examples and others as exceptional examples of whatever topic or form their work let us pursue. We also worked to represent the diversity of American life writing by breaking with established canons and including as many diverse authors as we could, not only to amplify marginalized perspectives but to reiterate that American identity itself is both fragmented and intersectional. But since we had a limited page count, we could only gesture at the full diversity and complexity of America’s life stories. HC: Some of the forms of life writing—like personal essay or memoir—seem like obvious inclusions. But I was fascinated by your choice to include aural narratives like podcasts and story slams, or online life writing such as blogs, as well as by your arguments for what makes particular examples of them more literary or consciously crafted. How did you decide what forms and subgenres to cover? AM&JT: The project focused on life writing rather than CNF as a whole, so we mostly focused on how and where people were telling life stories in public. That meant we couldn’t ignore the live performance and online forms, but also that we had to better understand the conventions and rhetorical frameworks of these forms. In podcasts, for example, we had to consider the role of the host who may or may not be the narrator whose experiences are under discussion, but who nonetheless becomes part of the story as they shape its insights for listening audiences. The chapter on memoir and autobiography is where subgenres became extra important. Certain memoirs get grouped into a conversation about particular subjects such as grief, parenthood, addiction, etc. We could have tripled that chapter’s length if we’d analyzed primary texts of every subgenre we listed, but the parameters of our contract prevented us from doing that. So, we had to make some tough calls about which subgenres seemed most prominent in contemporary memoir and expand our primary analyses there. HC: You alluded to the demands of page count ceilings and contract parameters, limits set by the publisher and/or the series. Writing and/or editing a textbook or anthology is a very different beast from writing a literary book. It takes time away from your own creative work, but a good one is such a gift to the community, so I again want to thank you for this tremendous service. How do you foresee it being used? What level are you pitching this at? AM&JT: Books that attempt to define categories often show how porous and indistinct those boundaries can and should be. We like thinking of our volume as bringing together different neighborhoods of the same larger community. So for writers and scholars, it can help bring people together from different specializations within CNF, but also historians, rhetoricians, and critics. The level of the volume is introductory, so we wanted it to be accessible for readers new to genre studies. In classrooms, we imagine the book would be useful in undergraduate or early graduate genre courses, or in creative nonfiction workshops where genre studies augments the writing and workshop process. We also hope to stock the book in libraries so that anyone looking for an accessible overview of American life writing will be able to find it. HC: How did you go about pitching this anthology to publishers? What was important to you? AM&JT: We think it’s important to be frank about how this volume came to be. Our department chair at the time, Quentin Miller, is also one of the editors for the Introduction to American Literature series at Routledge. When thinking about new volumes to add to the series, he landed on the idea of life writing. He suggested Amy pitch the project based on the work he knew she was doing in the classroom. Even though the project idea originated via a connection at Routledge, we still had to go through the standard process of writing a book proposal, having it peer-reviewed, and only then signing a contract. However, not acknowledging the professional connection that launched the project feels deceptive to us. This volume is a direct result of the networking that comes with a tenure-track position in academia. But once the proposal was accepted by Routledge (originally with a different co-author than Jason, who later had to back out of the project), we took the opportunity seriously. It’s daunting to write a survey that purports to define something as broad and malleable as life writing. We had to consider what that term really means, or rather, what it isn’t. For example, our decision not to include biography along with autobiography was all about feeling for the borders of the volume. Biography is no doubt life writing! But it differs from personal narrative, and we were most interested in the many ways writers account for their own experiences and how those accounts contribute to larger discourses. This is why literary journalism, where the author’s presence and ethos is part of the narrative, is included. We also wanted to ensure that our volume considered not only a range of forms of life writing but also a range of practitioners, from literary giants like Douglass, Didion, Baldwin, and Nin, to lesser-known authors and everyday people who underscore that nearly every American writes about their life in some form. The #MeToo movement, for instance, was a collective act of mostly ordinary citizens sharing about their experiences of sexual harassment and assault. Taken together, those narratives became a political force whose power (and complication) is still playing out. HC: You were definitely ambitious in your attempted coverage! Related to an earlier question, you were trying to do some literature review/overview of all these forms and practitioners. But with the relative lack of available nonfiction criticism and craft (relative to poetry and fiction), how do you cover that? What did you use for sources? AM&JT: This is where access to a university library helped us out big time—we were able to find many scholarly articles using our university’s database, especially when we needed historical information to contextualize our analysis. We also tapped Assay itself—an invaluable resource—and places like LitHub, Slate, and other publications that may not specialize in nonfiction criticism and craft but do examine specific texts that we could then showcase as representative of larger genre trends. But we also think you just participate in the conversation wherever you can, even if what you ultimately highlight is an opportunity for further scholarship. It seems like the job of a lot of research is to stick flags in those places where more research is needed. We tried to do our part and assemble something with a sense of connection, but it’s important never to assume you’ve found the last word on anything. HC: Since we’re speaking of life-writing, can you both talk a bit about the process of working with a co-editor who is also a spouse? AM&JT: We met in our MFA program at Ohio State, where we were both students and graduate teaching assistants. We quickly became personal partners, but we’ve also been professional partners in some way ever since. It’s beautiful how natural it feels to us, but we’ve never had firm borders between the two spheres. We talk about work constantly when we’re technically off duty. That’s where we call out ideas and make each other’s thoughts better. We wrote the book in pieces, collaborating on some chapters or sections and each of us fully drafting others that were then mutually edited and merged into the volume. We each have different orientations about things like process and deadlines, though, and that’s where cooperation and compromise are important. Amy prefers to write a little every day; Jason is a binge writer. HC: What did you like most about putting together this guidebook? What do you like most about this guidebook? JT: I really liked getting to investigate more connections and perspectives and histories than I would have without this formal reason to do so. I feel like it’s deepened our sense of context for ourselves as writers and teachers and literary citizens. AM: What I most liked writing were the primary text analyses because they required me to read and listen to texts I either already love or had always wanted to read or hear. What I like most about the volume is that it provided me with a mandate to declare my undying devotion to everything Melissa Febos has ever written. HC: When will this text be available, for instructors who want to use it in a course? AM&JT: It’s available now wherever books are sold! Teachers can also request desk copies directly from Routledge or ask their libraries to obtain a copy. Essayist and poet Heidi Czerwiec is the author of the lyric essay collection Fluid States, selected by Dinty W. Moore as winner of Pleiades Press’ 2018 Robert C. Jones Prize for Short Prose, the forthcoming Crafting the Lyric Essay: Strike a Chord, and the poetry collection Conjoining, and is the co-editor of The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing the Lyric Essayand editor of North Dakota Is Everywhere: An Anthology of Contemporary North Dakota Poets. She writes and teaches in Minneapolis, where she is an Editor for Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies. Visit her at heidiczerwiec.com

For Further Reading |