The Assay Interview Project: Amy Wright

April 18, 2022

|

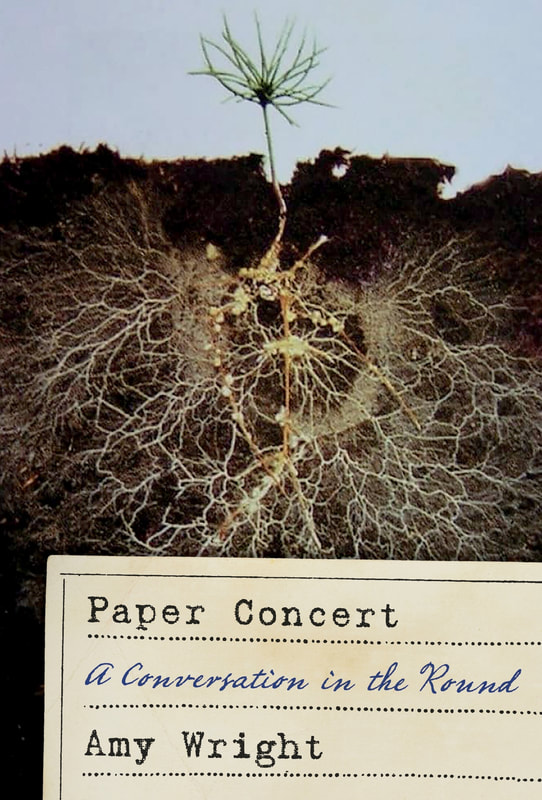

Amy Wright is the author of Paper Concert: A Conversation in the Round (Sarabande Books 2021) as well as three poetry books, and six chapbooks. She has received two Peter Taylor Fellowships to The Kenyon Review Writers Workshop, an Individual Artist Fellowship from the Tennessee Arts Commission, and a fellowship to Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Her essays and poems appear in Fourth Genre, Georgia Review, Ninth Letter, and elsewhere.

|

|

About Paper Concert: Folding together personal stories and conversations from a vast web of thinkers like Dorothy Allison, Rae Armantrout, Gerald Stern, Lia Purpura, Raven Jackson, Wendy S. Walters, Kimiko Hahn, Philanese Slaughter, and many, many more, Paper Concert depicts every individual as a collective in dire need of preservation. If this book is a paper concert, it is a symphony. Just pull up a chair and listen.

Eleni Sikelianos, Author of What I Knew, says: “A delightful, insightful, and nourishing book. I listened in on old friends and learned about many artists and thinkers I’d never heard of but who I will run out and learn more about. Like the ambitious, miracle-making spider that opens this book, Amy Wright spins a web that connects an array of fields and fields of thought. Touching on art, philosophy, race, class, poetry, ecology, and more, this is a good guide for the present disasters, leading us back along the strong lines of Wright’s web to what is most beautiful and inspiring in the human endeavor.” Mary-Claire Sarafianos: Paper Concert brings together myriad disciplines through essay and interview—including but not limited to climate change, class, race, empathy, and art. You yourself appear in the book in the short personal essays that frame your chapters, as the voice behind the questions, and even occasionally as the interview subject! In your first chapter, you detail the triumph of a spider you can see from your writing desk. She is spinning what seems like an impossibly wide web—but she manages it all the same! This image, and how it mimics your own book’s endeavor to spin a web of questions, paints your work as an essayist as not just an act of writing, but as an act of intricate weaving (and of fragmentation, to a degree). As you say, you “pull a thread of whole cloth” from the “patchwork document” you began with (6). What was your process when weaving these interviews together in this new configuration?

Amy Wright: Great synopsis of the book’s project, thanks! I had an advantage over the orb weaver that inspires its form: I came from a family of farmers and quilters who have been saving and repurposing everything from old blue jeans to apple skins all my life. Inevitably, I wanted to salvage the great stories, answers, and insights I have collected over the years. Art has always been applicable for me. The experiences interviewees have shared with me have informed and augmented my life in countless, internal ways. I wanted to share those offerings and my practice of asking necessary, hard, and sometimes unanswerable questions. I hope the form inspires others—in the way Studs’ Terkel’s Working inspired me—to take into account a range of perspectives. The essential offering of Paper Concert’s “Conversation in the Round” is that it gathers voices across disciplines, decades, and cultures, reminding us to check who has access to the conversations that matter to all of us. Political, environmental, and social decisions are made annually that impact us globally, but how many points of view get taken into account? We need to evolve forms that express the collective, if we want to sustain, much less advance, our species. This book centers around interview and conversation, but there is also a fascination with sound itself—both its presence like in the buzzing of news bees in your childhood and its absence like in the silences that your interview subjects author Rebecca McClanahan and poet and filmmaker Raven Jackson give meaning to in their work. How did you contend with the nuances of sound in this book—whether that be someone’s voice, inflection, or pauses? How did you think about translating these sonic aspects into writing? What is the role of the unspoken in this book? Ah, great question! Thank you for picking up on the use of silence in the book. My informal education as a child of Appalachia was largely in the art of implication. My mother was masterful in her use of body language and long pauses. Too, my grandparents knew what goes unsaid can be more memorable and authoritative than what is. Like unsnapped photographs, unspoken speech lingers in our memories. Sometimes it reverberates louder than a shout would. What gives Raven Jackson’s films and poems power is her ability to listen to silence, such as the hesitations that complicate and layer the Black women and girls that inhabit her work. We are not often free to express ourselves fully—nor equal in that freedom. The unsaid reflects our limitations sometimes and, at others, the power to hold our tongues. It pays homage to those who reach beyond words to express themselves. Silence also invites readers to participate in the act of communication. As Rebecca McClanahan notes, “a reader completes the transaction we writers set into motion.” It’s essential to protect time and space for listening, or an exchange becomes a diatribe, monologue, or sermon. That’s why I think of the book as a concert: composers understand that the timing of the rests in music are equal to the notes for the final composition. The interviews in this book span eleven years’ worth of work—that is a huge amount of text and time! Can you speak to the role of curation, documentation, and even keeping track of your materials in the process of writing this book? In the end, the interviews actually extended over thirteen years, as I added new perspectives to the conversation. If Sarabande hadn’t set a deadline, I might still be adding to it. I don’t have much patience for organizing, say, my glove compartment or freezer, but I save and file all writing I might use or need later. If my computer’s search function and storage capacity extended beyond digital files, maybe I would curate my life! It’s an appealing idea anyway, that learning is cumulative. Curating my archive of dozens of interviews by categories like climate crisis, class, and gender showed me, though, that wisdom doesn’t add up so much as intersect. We are all tempted at some point, usually in times of hardship or uncertainty, to seek something like a how-to guide for life. Growing up on a farm, I needed art to be viable. Otherwise it might seem a luxury and superfluous, so I have long argued with those who prize aesthetics over application, as if they are separable. To some extent this book stands as proof that art is a treasure trove of usable questions, jokes, advice—and beauty. Yes, art can shock and awe, but it can also probe, hammer, glue, and glove. There are two moments in Paper Concert where you place yourself in the text as a participant in a conversation rather than as an interviewer. These moments, both with painter Marc Gaba, touch on themes of creation, artistic process, trust, desire, and secrecy. Can you talk about your choice to enter the conversation as an equal participant at those moments? There’s the danger and privilege of having your name on a book cover: everything that happens inside seems to be your choice! In fact, it was a collaborative gesture when Marc turned the table of the interview on me. My choice entered mostly in where I positioned that surprise in the arc of the book. Marc and I met in grad school and have been friends since, so the interview hierarchy was leveled from the start. His was also one of the earliest interviews I conducted, so I told him my vision for what I was calling at the time flash interviews. I wanted to spotlight the sparks of insights that pass between friends in deep dialogue. Mark was perfect for that project, since—as you might guess from his passages in the book—he speaks with fearless originality. He also trusts his curiosity and asks smart questions, so my experiment was gratifying. Our conversation continued in various forms for years afterward, but when I edited that excerpt for publication I recognized why interviews are more often one-sided. For ease of reading, I cut my answers and the questions he posed to me, though I saved the transcript. When I began compiling the essay that became Paper Concert, that unpublished intimacy between friends was the perfect complement. What, for you, is the difference between a conversation and an interview? I use the word interview out of convenience, but I’m only ever interested in dialogue. There’s a line from The Catcher in the Rye relevant in this context. Salinger writes: “What really knocks me out is a book that, when you’re all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours.” Part of the joy of reading, or listening to music, or learning about a new scientific study is what it reveals about the person behind it. Conversations are character portraits; interviews are industry byproducts. I participate in the latter, as reader and author, and sometimes as interviewer, but I also circumvent capitalism when I can by using the forum to give away invaluable nuggets of gold. What does it mean to you to be part of a book where you are also the intermediary? They may not be the most honest moments in the book but they are my most honest ones, because I risk vulnerability comparable to the other contributors. I will always be grateful to Marc for inviting me into that role and trusting his instincts to lead us there. And finally, to borrow a question from you: when in your life have you felt freest? I was working as a web designer in D.C., my first full-time job. I spent my days running code into scripts that would translate pamphlets and meeting photos into digital programs for a non-profit. Every day I ate lunch with a retired bird colonel in the Air Force. After work, I took the elevator to the bottom floor of our office building and sweated on the elliptical trainer in a mirrored workout room, then took the Metro home to a two-story rental I shared with three young women I saw only on weekends. I joked with the poet Rod Smith that I was writing a book called The Disappointing Universe. Then, one day, I bid $97 for a flight to Colorado on Priceline. When I won I told my mother, who asked, “Did you buy a ticket back?” My ticket was round-trip, but she was onto me. My escape had begun, which would lead toward grad school and an altogether different life. Mary-Claire Sarafianos is an MA/PhD student studying silence and structure as both problems in archives and as themes in nineteenth-century American women’s writing.

For Further Reading |