The Assay Interview Project: Edvige Giunta

October 1, 2023

|

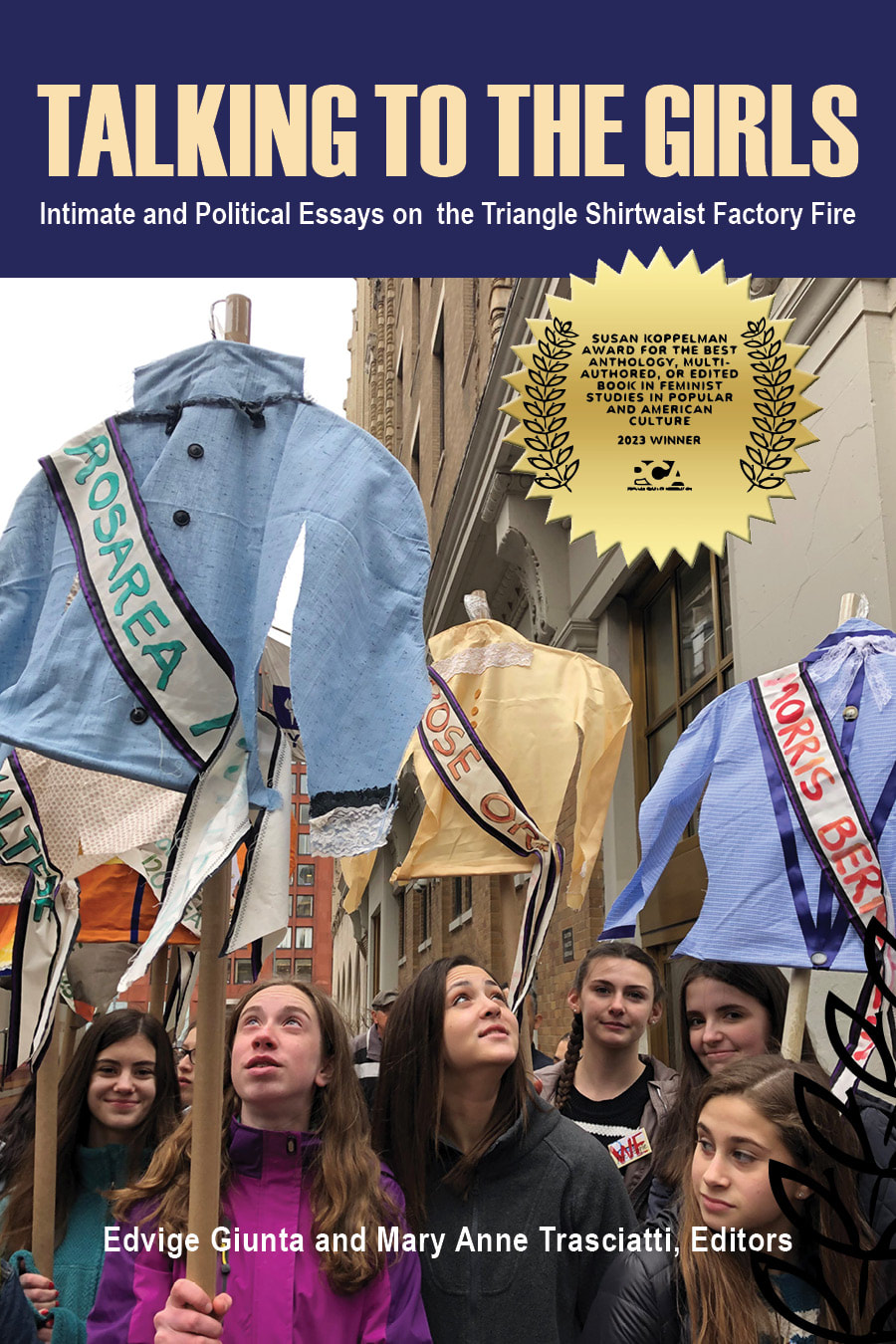

Edvige Giunta is the author of Writing with an Accent and coeditor of several anthologies, including Talking to the Girls: Intimate and Political Essays on the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, edited with Mary Anne Trasciatti. Talking to the Girls received the 2023 Susan Koppelman Award for Best Anthology in Feminist Studies in American and Popular Culture. Most recently, Giunta’s writing has appeared in December Magazine, Hinterland, LSE Review of Books, and The Adroit Journal. She was a featured writer in the Ocean State Review. She has completed a book-length memoir and is working on a flash manuscript. She is Professor of English at New Jersey City University.

|

|

About Talking to the Girls: Intimate and Political Essays on the Triangle Fire: this powerful collection of diverse voices brings together stories from writers, artists, activists, scholars, and family members of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory workers.

On March 25, 1911, a fire broke out on the eighth floor of the Asch Building in Greenwich Village, New York. The top three floors housed the Triangle Waist Company, a factory where approximately 500 workers, mostly young immigrant women and girls, labored to produce fashionable cotton blouses, known as “waists.” The fire killed 146 workers in less than half an hour but pierced the perpetual conscience of citizens everywhere. The Asch Building had been considered a modern fireproof structure, but inadequate fire safety regulations left the workers inside unprotected. The tragedy of the fire, and the resulting movements for change, were pivotal in shaping workers' rights and unions. Talking to the Girls brings together the work of nineteen contributors from across the globe to speak of a singular event. One hundred and eleven years after the tragic incident, this book articulates a story of contemporary global relevance and stands as an act of collective testimony: a written memorial to the Triangle victims. Julija Šukys: Edi, congratulations on your success with Talking to the Girls. The book is a collection of essays that intersect with, reflect upon, or examine the 1911 Triangle Fire in New York City. I suspect many of our readers won’t know much about the fire, so please tell us the story of the fire and your connection, as a native Sicilian, to it. I was fascinated to read about the ways in which the fire’s history has been mapped not only onto New York’s geography but also onto Italy’s.

Edvige Giunta: Thank you so much. To receive the Susan Koppelman Award was deeply moving for all of us involved in the book—my coeditor, Mary Anne Trasciatti, our contributors, the director of New Village Press, Lynne Elizabeth, and the community of Triangle families and activists. For almost three decades, editing has been central to my work. After five anthologies, a journal, and several other editorial projects, I knew that Talking to the Girls would be my last edited book—so receiving the award was particularly meaningful. I have felt the call of Triangle for most of my life—as a feminist steeped in the history and culture of my native island of Sicily (where I first heard about the fire), an immigrant, a native speaker of Italian who writes almost exclusively in English, a scholar of Italian American women authors, a memoirist, a teacher dedicated to disenfranchised student populations, a cultural worker committed to intercultural exchanges and alliances. Doing this book was one response to this call. The Triangle fire was the largest workplace fire in New York City until 9/11, a disaster with which it bears some eerie similarities, like the images imprinted in the collective memory of people jumping to certain death to escape a fire. Conversations about these two events continue to raise questions about the relationship between public and personal memory in their memorialization. The Triangle Waist Company was housed in a building deemed fireproof. That March 25th, 1911, 146 workers died in a fire caused by the neglect, if not the absence, of fire safety regulations, by locked doors and failing fire escapes, by greed and indifference. While the conditions at Triangle exemplified a pervasive disregard for the lives of low-wage workers in New York City and the US at the time, something separated Triangle from other factories. In 1909, the Uprising of the 20,000 saw not only the largest number of women workers to strike until that time, but also a cross-class alliance between garment workers and the upper-class women of the suffrage movement, like Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, Anne Morgan, and Fola La Follette: this alliance brought attention to the strike. Many factory owners negotiated with the workers. Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, the Triangle owners, however, stood firm in rejecting union representation inside the factory. This decision perpetuated the conditions that were ultimately responsible for the fire. The Triangle workers were, for the most part, Jewish and Italian immigrant women and girls, as young as fourteen. Families were decimated, as was the case for the Maltese family: Catherine (age 39) and her two daughters, Lucia (age 20) and Rosaria (age 14), died that day. The factory owners were indicted for manslaughter but were later acquitted. They ended up making quite a bit of money through the insurance. In its aftermath, the Triangle fire prompted major legislative changes to protect the safety and dignity of workers. Frances Perkins witnessed the fire: its horrors strengthened her resolve to fight for the rights of workers, as she did, notably, as the first woman to serve as US Secretary of Labor during FDR’s presidency twenty years later. It is widely believed that the Triangle fire started the New Deal. The social awakening that followed the fire led to a political mobilization that continues to be a point of reference for workers fighting against exploitation in the US and worldwide. Most of the Italian workers who died in the Triangle fire came from Southern Italy, especially Sicily. Through an initiative of the organization Toponomastica Femminile (discussed in Ester Rizzo Licata’s essay in the book), commemorative sites have been created in the birthplaces of these workers. In political, literary, and artistic circles in Italy, there has been growing interest in the Triangle fire as a key chapter of Italian migration. This interest is especially poignant at a time when Italy is grappling with a massive migration flow, especially of refugees from African countries. Reckoning with Italy’s own history of migration, and what caused it, is instrumental to framing the conversation about late twentieth-century and twenty-first-century migration into Italy. Scholars of post-colonial Italian literature like Caterina Romeo have pulled together these threads as well as that of the Italian colonization of African countries, especially during fascism. You describe the book’s pieces as relying on “the principles of creative nonfiction.” They are imaginative, personal, and intimate, yet deeply informed and researched. We find all kinds of voices here: those of scholars, writers, performers, activists, and descendants of the fire’s victims. Tell me about the solicitation process for this collection. How did you describe what you hoped your contributors would produce? Whose submissions surprised or impressed you? Why has the memory of the Triangle fire been embraced by so many people in contemporary times? How has the legacy of Triangle taken root in people’s lives in a multiplicity of cultural and professional contexts? What kind of activism has Triangle inspired? Who are the people who remember Triangle and what does their memory work look like? What are their stories and how can they be told? What has been forgotten, obfuscated, or remains unknown? These questions informed our vision of the book. We trusted that the exploratory nature of the work that we hoped our contributors would pursue would be best expressed through creative nonfiction. We told our contributors the scope of the book was not to provide an overview of the history of the fire or a compendium of scholarly perspectives or an overview of political and cultural initiatives surrounding the fire over the last century. Instead, we invited them to write essays that would collectively offer a simultaneously intimate and political view of the historical and cultural legacy and resonance of the Triangle fire today. Although research would be important, we wanted the essays to be viscerally personal. Opting for an inclusive bibliography and an Appendix where each author reflected on the sources for their essays freed the book from the traditional scholarly apparatus while also honoring the archival and historical research that sustained the work. It was essential to include family members of Triangle workers, like Suzanne Pred Bass, whose two great-aunts worked at Triangle—one who died in the fire and the other who survived by grabbing and sliding down the elevator cable as it left the burning ninth floor; or Martin Abramowitz, whose father worked at Triangle and testified at the trial, and might have been the one who inadvertently started the fire by discarding a live cigarette ash. We also wanted to include people who had direct connections to witnesses of the fire, and so we invited, for example, Tomlin Perkins Coggeshall, Frances Perkins’ grandson, and Annie Schneiderman Valliere, great-niece of labor activist Rose Schneiderman. There is no quintessential form of Triangle activism or Triangle story. Thus, we included authors who have incorporated Triangle in a variety of lived and professional practices, who have an ongoing engagement with contemporary issues related to Triangle. The principles of creative nonfiction made possible the layered work we engaged in as editors and contributors. Some contributors had a story about the fire that they had told again and again in other contexts. That old story may have been the initial impetus for their writing. As editors, we helped our authors defamiliarize themselves with their stories to undertake fresh work of excavation. We worked closely with our contributors over multiple drafts so that they would produce essays that collectively composed a choral narrative meditation on a fire that happened over a century ago—and is still making new memories. We wanted the book to inspire the readers’ own memory work. We had to urge some writers to dig deep into the role of the personal in their historical and cultural narratives. Personal writing remains strangely suspect in academic discourse, as if lacking in authority. Activists might feel that writing about oneself is an act of self-indulgence that goes against principles of political integrity. On the contrary, the intermingling of the intimate and the political generates the radical heartbeat of Talking to the Girls. Some authors were satisfied with their initial submissions and were not comfortable with the intimate and political form or the many layers of revision it involved. We had to make the difficult decision to let go of the work of writers we deeply respected and would have loved to include in the book. But the essays had to work together because we were not merely collecting. We were fabricating a multivoiced book, a book that was taking shape at the same time as the Triangle Fire Memorial was being created. For this reason, all these essays were written for Talking to the Girls—we did not include any reprints. The last stage of revision, after the essays were close to finished, posed another challenge. It can be tricky to edit an anthology that focuses on a singular event: each writer repeats certain key facts. We had to know all the components of each essay intimately so that we could help reshape them when needed. We situated the essays in a map of the book where we differentiated between fresh historical information and echoes so that redundancy would not compromise the flow we wanted the book to realize. There was a lot of cutting and restructuring. For example, initially, “Families” was the first section, but we ended up placing “Witnesses” first, and we opened the book with an essay that was not an obvious Triangle essay, or an essay that focused on direct witnessing. In “Another Spring,” Annie Lanzillotto weaves her commitment to the memorialization of Triangle workers and her predicament as a working-class artist pushed out of her home by gentrification, her peregrinations through the neighborhoods of Triangle workers to “chalk” their names and her travels through the birthplaces of the dead to draw a “wounded” map of Sicily. Annie’s essay prompts readers to become witnesses themselves and to look for connecting threads in and among the other essays. All essays surprised and thrilled us: each connected the intimate and political differently. May Chen, a leader of the 1982 Chinese American garment workers strike, wrote of her political journey and the history of her involvement in the union by including deeply personal moments, from confronting racism in her youth to chalking for the Triangle workers with her grandchildren. Annelise Orleck juxtaposed her work as a historian of the Triangle fire, and of contemporary global labor activism, with reflective biographical narratives of her grandmother Lena, who worked at Triangle, and labor activist Kalpona Akter. There is such vulnerability in these essays, like the pedagogical essay by Jacqueline Ellis, where her experiences as a teacher of working-class students and as the white mother of a Black child intersect with her discussion of girl activists, from Clara Lemlich to X Gonzales; or Michele Fazio’s essay, in which peeling the layers of family history and labor history become inseparable tasks, part of one story with necessary and illuminating digressions. I can’t remember the last time I came across creative work that interfaced with labor movements, unions, and activists in the way Talking to the Girls does. The way that you draw a line from 1911 to today is very impressive. The book does this organically (or so it feels to the reader), and it makes a direct connection between the working conditions of New York’s female garment workers more than a century ago to those of garment workers in Bangladesh today (the Bangladeshi activist Kalpona Akter, whom you refer to above, appears as a kind of touchstone figure in the book). Talk about this connection that you and your contributors have made and of tackling labor and international labor movements as a literary theme. Talking to the Girls is anchored to the legacy of the Triangle fire as living history—and labor is at the center of this history. While the structure of the book kept morphing, we always knew it would end with Kalpona Akter, with her experiences as a child garment worker and a leader of the Bangladeshi labor movement whose voice resonates internationally. Disasters like the Tazreen Factory fire and the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh are terrifyingly reminiscent of the Triangle fire. Kalpona’s words at the Triangle fire centennial in New York City—“In Bangladesh it’s not 2011. It’s 1911”—exemplify that direct line that connects Triangle with today’s factory workers, especially in developing countries. The history of labor is the story—the stories—of people, of families, of communities. There is poetry in these stories, and the genre of the personal essay allows for the expression of that poetry, not only in the lyrical essays of poets who had written Triangle fire poetry, like Paola Corso and Annie Lanzillotto, but in many of the essays, like the essay of Richard Joon Yoo, whose initial task was to write an essay as a member of the two-architect team that designed the Triangle Fire Memorial. As his essay took shape, it incorporated a meditation on his memories as the child of Korean immigrants. We encouraged our contributors to slow down the writing in key moments, and to rely on strategies of memoir such as scene, summary, and reflection. We were constantly looking for openings, for what had been left unspoken, unexplored, or too compressed in the essays—for what remained unknown. As editors and contributors, we developed such reciprocal respect and trust in the process. We understood that this book was asking us to undertake together a profoundly affecting and transformative journey. The essays do not simply recount—they evoke and reflect, they create echoes and connections; they acknowledge the void of the forgotten, the pull to remember, the struggle to find a form to articulate intergenerational trauma, the power of questions doomed to remain unanswered. Even though I haven’t yet asked you anything explicitly about race or gender, you’ve anticipated my question somewhat, above. Both race and gender are central as themes here. First, it’s impossible to ignore the fact that the majority of the Triangle fire victims were women, and most of them were recent immigrants. Second, the breadth of cultural backgrounds we find amongst your contributors is striking. Your contributors come from Italian, South Asian, East Asian, Caribbean, and Jewish communities. What role did gender and cultural history or race play in your thinking around curation and editing? Mary Anne and I edited this book with a constant awareness of the politics of gender, class, and race. We wanted to highlight that Triangle was primarily a tragedy of women and girls—sixty-five teenage girls died in the fire: their names are listed at the end of our introduction, and the book’s title and cover image pay tribute to their memory. But Triangle is also the history of the absence of Black women from Triangle, examined by Janette Gayle through her experience as a labor historian and a Black immigrant woman. Gayle’s essay exemplifies the kind of writing we aspired to include, writing that brings to light little known historical facts such as the exclusion of Black women from the garment industry. This writing illustrates the historical reverberations of gender, class, and race politics in Triangle history. To articulate a vision of Triangle that both honored and transcended its time and context, we recognized the importance of the Jewish and Italian voices and stories, but also wanted to show that Triangle speaks to people from different backgrounds and constituencies, including people who have no direct connection with the factory through identity including gender, ethnicity, race, and nationality. Thus, we reached out to a diverse group of contributors. We trusted that the juxtaposition of different experiences, vantage points, and activisms, of different relationships to Triangle history, would produce a richly layered conversation, one that would show the power of Triangle memory and legacy across time, space, and cultures. Memory is also central to the project. Your book asks continually: how can we remember, commemorate, and give voice to the dead? Many beautiful rituals have developed to mark the Triangle Fire: chalking names, flying shirtwaist kites, marking birth places on the other side of the Atlantic. You yourself have taken part in such memorializations and have developed an entire university-level course around the Triangle Fire. Talk about what taking part in this kind of collective memorialization has taught you and what you have learned, in turn, by translating and teaching your students this history. When we started editing Talking to the Girls, Mary Anne and I had decades of shared and separate involvement with different forms of memorialization of Triangle. Together, we had organized panels and chalked in NYC with our students. I was working on pedagogical approaches to creating commemorative projects with the students of the Triangle fire course I had developed at New Jersey City University in 2017. As the President of the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition, Mary Anne had been working tirelessly for over a decade to realize the Triangle Fire Memorial, the first labor monument in NYC and one of the first dedicated to women—the Memorial will be inaugurated on October 11, 2023. There was such synergy in our work. When our publisher called Talking to the Girls a “written memorial” to the Triangle fire, it rang true. In the last section of Talking to the Girls, “Memorials,” art historian Ellen Todd traces the history of the memorialization of the fire in different times and forms. But all the essays explore the question of how Triangle is remembered. In each essay, there is this seesaw of past and present—and the past is not limited to Triangle history. It’s the story of the Mexican migrant workers who died in the Los Gatos plane crash of 1948 that Laura Ruberto writes about as she reflects on how to remember the Triangle fire in California. It’s the story of Richard Joon Yoo’s parents’ emigration from Korea, of Kimberly Schiller’s memories of her mother’s activism, of Ellen Garvey’s friendship with the daughter of Sophie Sasslovsky, of Paola Corso’s sewing lessons in school, of Janette Gayle’s experience as a domestic worker after immigrating from Jamaica. Historical and personal, past and present, coalesce into one layered narrative that keeps shifting through every essay: there is no formula. My own encounter with the Triangle fire was in itself a kind of memorializing. At seventeen, I hosted a feminist program at the local radio in my hometown of Gela, Sicily, and spoke of remembering a fire that had occurred at the beginning of the twentieth century in New York City and had inspired International Women’ s Day. A year later, as a college freshman, I participated in feminist marches where we remembered the fire and sang a song by the Movimento Femminista Romano, in which women who had died in a factory fire asked to be remembered—“remember us.” I would have to move to the United States to learn that the fire had not occurred on March 8th but on March 25th, that the factory was called Triangle Waist Company, and that one third of the workers who had died were Italian-born or first-generation Italian immigrants, most of them from Sicily. In 2001, I organized the ninetieth commemoration of the Triangle fire with historian Jennifer Guglielmo (of which were were both members), the Collective of Italian American Women, and Casa Italiana Zerilli Marimò at New York University (NYU now owns the building where the fire occurred). We stood in front of the building that once housed the factory and shouted the names of the 146 workers. I called out the name of seventeen-year-old Isabella Tortorelli. This intimate connection with memorializing “the girls” is at the heart of Triangle activism, and it is also at the heart of my teaching. The “Name Project,” the first assignment in my Triangle fire course, is a memorial project born of this work of memorialization. It begins with each student choosing, and remembering, a name from the list of the 146 dead. Then they research the life records of that worker by consulting, first of all, Cornell University’s Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, a phenomenal source for Triangle research. In reconstructing the life of their worker, they must confront the scarcity of records. That impasse becomes a creative opportunity to reflect on the absence of the narratives of working-class lives in traditional historical narratives. In March, they work on a memorial chalk project (CHALK, created by Ruth Sergel). Finally, they write a personal essay that includes their discoveries, experiences, and realizations. The whole course revolves around the memory work that we do individually and as a community: attending Triangle fire commemorations, carrying shirtwaists with the names of the workers, chalking, participating in panels on the NJCU campus and elsewhere, going to the Fashion Institute of Technology in 2019 and sewing together pieces of fabric into the Collective Ribbon that has been used to cast the Triangle Fire Memorial, working through final projects that range from a ballet performed at Washington Square Park, to handmade shirtwaists with bits of the fabric burnt, to paintings and other visual art projects, to hybrid essays that connect Triangle history with students’ own experiences—for example, as a witness to the Arab Spring, as an immigrant, as an essential worker during the Covid lockdown. Increasingly, America seems to be the land of oblivion. Mass tragedies occur here on a shockingly regular basis, yet they are forgotten almost immediately – ever more quickly, it seems. Do you think the Triangle Fire memorialization can teach us how to remember better, as a society? Have you found any hope or wisdom in this work and history? Absolutely. The dedication of so many people to the memory of the Triangle workers speaks volumes. Empathy, solidarity, advocacy, creativity, social responsibility, generosity, and a heartfelt sense of community—these are all part of my experience working with the Triangle community. A few months ago, while giving a virtual talk about the fire at St. Andrews University in Scotland, and conducting a workshop on memory and history, I became aware that an audience member was the great-great-granddaughter of Anna Pasqualicchio Ardito, who died in the Triangle fire. There it was, one of those unexpected encounters that are inevitable once you become involved with Triangle history. Recently, I saw her again when she attended a memoir workshop that I taught for Triangle fire families and activists. It was extraordinarily moving to see her again, especially in the company of family members of other Triangle workers and activists. I felt so honored to play a small role in helping this group remember and tell stories born out of the traces of an event that happened 112 years ago—a living memory that has the power to connect us with each other, to become advocates, to act. Triangle calls us to remember and to believe in social justice, in resilience, in persistence, in righting wrongs—and heeding that call moves us to become our better selves. Associate Editor Julija Šukys is the author of three books (Silence is Death, Epistolophilia, and Siberian Exile), one book-length translation (And I burned with shame), and of many essays. She is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin and, in Fall 2022, held the Fulbright Canada Research Chair at York University in Toronto.

For Further Reading |