The Assay Interview Project: Elizabeth Rush

January 1, 2019

January 1, 2019

|

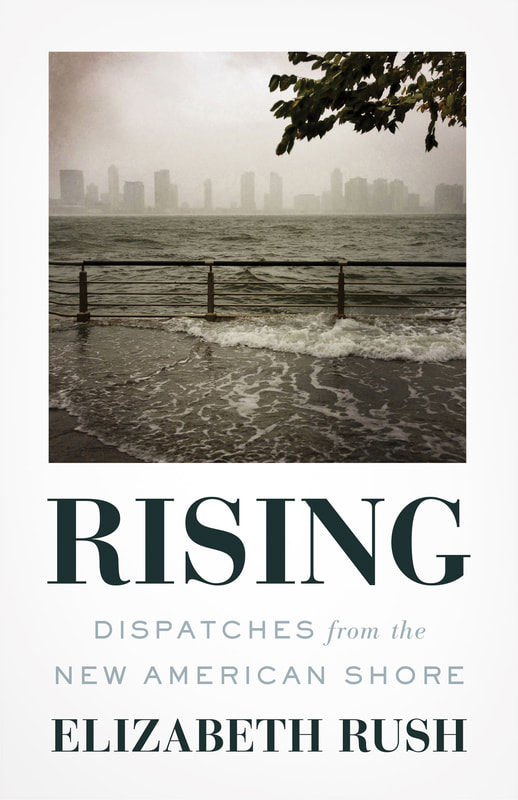

Elizabeth Rush is the author of Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore and Still Lifes from a Vanishing City: Essays and Photographs from Yangon, Myanmar. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in the Washington Post, Harpers, Guernica, Granta, Orion, and the New Republic. She teaches creative nonfiction at Brown University.

|

|

About Rising:

Harvey. Maria. Irma. Sandy. Katrina. We live in a time of unprecedented hurricanes and catastrophic weather events, a time when it is increasingly clear that climate change is neither imagined nor distant—and that rising seas are transforming the coastline of the United States in irrevocable ways. In this highly original work of lyrical reportage, Elizabeth Rush guides readers through some of the places where this change has been most dramatic, from the Gulf Coast to Miami, and from New York City to the Bay Area. For many of the plants, animals, and humans in these places, the options are stark: retreat or perish in place. Weaving firsthand accounts from those facing this choice—a Staten Islander who lost her father during Sandy, the remaining holdouts of a Native American community on a drowning Isle de Jean Charles, a neighborhood in Pensacola settled by escaped slaves hundreds of years ago—with profiles of wildlife biologists, activists, and other members of the communities both currently at risk and already displaced, Rising privileges the voices of those usually kept at the margins. At once polyphonic and precise, Rising is a shimmering meditation on vulnerability and on vulnerable communities, both human and more than human, and on how to let go of the places we love. Karen Babine: Elizabeth, first, congratulations on your book! It is an essential continuation of the conversation about the relationship of humans to their environment, even as we are watching environmental protections deliberately decimated every day, and I’m so thrilled to be able to talk with you about it. This summer, I’ve also been very aware that the relationship between land and water, too, is a fraught one. I live in Minnesota, where we are watching two environmental disasters-in-waiting emerge, the proposed Line 3 pipeline that would go through the Headwaters of the Mississippi River (and the Lakes Country of northern Minnesota) and the constant threat of new mining in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. One of the great things about your book is that while the topic itself is specific to sea level risings on the coast, the concepts are applicable to any environmental conversation around climate change and the push-and-pull between people and the environment.

Immediately, it’s clear that naming plays an important role throughout the book: in “Persimmons,” you write of “The hundreds of dead cypresses and oaks. And the fishing camps destroyed by Rita. Past Theo’s parents’ old home, and Lora Ann’s old home, and Albert’s old home, and all of the other residences that have been abandoned because rebuilding is tiresome and expensive” (25). In “The Password,” you write of learning the names of the dying trees and other plants in the marshlands of Rhode Island and you quote Robin Wall Kimmerer, in that “naming is the beginning of justice.” How does this play out in human justice, with Twitter hashtags like #sayhername? The way you consider different modes of naming brings to mind Paul Gruchow’s essay “Naming What We Love” from Grass Roots: How does naming the plants and birds around us support environmental justice and combat a mentality that would ask who cares about grasses when people are suffering? How are fairness and justice not the same thing? Early in the process of writing Rising, I realized that tidal marshes where going to be central to this book. They are, by their very nature, low-lying and vulnerable. The more time I spent in these wetlands the more I realized that I didn’t know the names of the different plants and animals that comprise these communities. That’s because wetlands have long been thought of as wastelands, as the source of disease and the home of marsh monsters and serpents. I didn’t know the names of the things that live in these places because these landscapes have been overlooked if not downright denigrated through history. So I set out to learn how to identify and understand the beings that have long lived at the water’s edge. The more I learnt about them––their names and also the conditions they thrive in––the more I understood how our cultural devaluation of these landscapes plays a large role in producing their vulnerability. We have no problem paving over a field of black needle rush while the idea of doing the same thing in an old growth forest sacrilege. When we say the sames of the beings––people, plants and animals––that have been harmed because the dominant history tells us that they are lesser we begin to counteract that narrative. With naming comes not only a claim for equality but also hopefully a call to understand what produces vulnerability in the first place. This idea, that vulnerability is not arrived at by chance, is central to the book. And yet, you conclude your book with an Afterword titled with the names of recent hurricanes, the personification of weather. The other sections have been voiced by those you’ve interviewed; how did you make the choice to give the final voice to something that is not human? So much of the book is dedicated to giving voice to those who have been silenced by conversations about climate change, particularly people who live in those areas whose insight and opinions about the subject have largely been ignored in favor of people from Elsewhere making decisions on their behalf (without consulting them, in many cases). You could have ended with one of the people you interviewed, giving them the last word in the book, but you didn’t--you chose to give the last word in the book to the hurricanes instead. What was behind that choice? I think of the final chapter as mirroring the opening essay, which explores the importance of learning the names of the more than human animals and plants that are dependent upon tidal wetland ecosystems for their survival. Just as I think we need to say the names of the species that are being threatened by sea level rise, I think we also need to say the names of the super-charged hurricanes we have constructed, are continuing to construct. Because in naming and pointing towards these storms we learn to acknowledge our own culpability in putting so very many of us at risk. We used to think of climate change as a problem for the future but it is very much with us now, in the present tense. In September of last year one in ten US citizens was living in a county with a disaster declaration. The idea of settling and unsettling is a strong thread throughout this book. You write of pre-contact peoples who “shaped their civilizations around the Mississippi’s ebb and flow” (28). How did you consider the larger consequences, beyond the obvious, of colonizers building civilizations of stones that could not move, based on the supposition that “the Mississippi’s regular high waters and sediment-delivering surges were described as a deterrent to human progress” (29). Was its effect that humans could no longer evolve and adapt as part of the existing ecosystem? Later, you interview Richard Santos, who says, “The trains all ran through town and the hobos would jump off, and my father—he eventually became the police chief—he would greet them right there and ask, ‘Are you working?’ If you said no, he put you in a car, drove you to the outskirts of town, dropped you off and told you never to come back” (207). We have not come far from a time when migratory people were suspicious, people who were unsettled were considered undesirables, even dangerous. First let me say that your pointing towards the idea of “unsettling” as being a strong thread through the book is spot on. One of the early subtitles for the book was “The Unsettling of the American Shore” (a nod to one of my favorite environmental writers, Wendell Berry.) As to your second point, about how in post-contact North American nomadic peoples and newer migrants were treated with suspicion you are right. But I don’t think this kind of thinking is a thing of the past. These value judgments continue into the present moment. When someone from Mexico, Central or South America crosses into the US without papers many people call them “illegal.” With that word comes a whole host of negative connotations that seeks to undermine, consciously or not, that person’s basic human rights. Which is to say unsettled people are unsettling to a certain set of myths around America that say that land ownership is how we lay claim to a home place. I think, at least where sea level rise is concerned, we need to learn to let go of our static image of the coastline. One of the reasons this is so hard for us to do at the present moment is because over the past two hundred years we have dammed, diked and drained over fifty percent of the marshes and wetlands that lined our shores so that they might become private property. And not surprisingly with sea levels rising, many of these places are now flooding worse and worse, year after year. In this way sea level rise is unsettling our ideas of who we are and where we come; it is destabilizing one of the biggest myths of America––the idea that we can and ought to place borders around very particular parcels and in the process get to call them our own. As our lowest lying communities are inundated we will have no choice but to move, making migrants out of so very many. The sooner we can wrap our minds around this idea the more likely it is that we will be able to move away from rising risk in as egalitarian manner as possible. It seems that, as settlers on this continent, we remain suspicious of movement. I have a friend who often comments that the African American community needs an updated version of the Negro Motorist Green Book (which I often assign when teaching travel writing), but even as I was searching for it, New Orleans writer Jan Miles released The Post-Racial Negro Green Book in November 2017. It is obvious that our margins are populated by people of color, along all our coasts and arrival points, and when those margins are underwater, marginalized people will suffer further. Do you see a path forward to avoid this? Indeed, many lower-income coastal residents are already being displaced by higher tides and stronger storms. I was just in Houston reporting on the Harvey recovery and many of the folks I spoke with were actually Katrina survivors who started over in Texas. One of the reasons they might not have gone back to New Orleans is because, as a result of redlining, property values in many of the neighborhoods hardest hit by Katrina were long suppressed. When those folks received federal recovery funding it often did not cover the most basic act of rebuilding, because the amount they received was tied to the artificially low property value. So instead of going back (which they could not afford even with assistance) they started over elsewhere. By 2050 we are going to have 200 million climate refugees worldwide, 2 million of them from the state of Louisiana. I think we need to start having a public conversation around managed retreat. How do we move away from risk in an egalitarian manner? We have a small federal program that helps residents living in the floodplain move away from risk. It is called the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and I would like to see the program grow in the years to come. In order for it to grow people need to know it exists, which is why it is so important to have these public conversations about retreat as a form of resilience. The chapter “Persimmons” closes with Edison gifting you a persimmon, which leads to a moment of epiphany: “It is a taste I have never encountered before. And in that moment I think I know why he and the others do not leave” (41). One of the primary conflicts in this book is the distance between insiders and outsiders, between people who know the language of a place and the people from elsewhere who often hold different priorities. As you were writing this book, how did you manage to navigate this distance on the page? You move from a distant journalist-narrator to a very close participant on the page, between journalism and giving first-person voice to the people themselves. What kind of craft choices did you make as you drafted to navigate between them? I have never really considered myself a journalist in part because I am suspicious of the claim that any kind of writing, journalistic or otherwise, might be able to be objective. Every decision one makes from what kinds of stories to cover, to how carry out researching and writing a piece shapes the end result. Which is to say that to write Rising I didn’t exactly act like a traditional journalist. To write each of the nine chapters that comprise the book I spent months (in the case of Staten Island, years) in these communities that are being changed by changes in the climate. Many journalists will do a series of short interviews to write a piece (often no more than 30 minutes a pop.) The relentlessness of the 24-hour news cycle demands that they do not spend more. To write Rising, my engagements were considerably longer and as a result much more personal. Through the process of writing a piece I would often undergo a kind of transition, from outsider to insider (or as close as someone not from there could get.) I worked hard, over time, to lessen the distance between myself and my subjects. Instead of driving my rental car into a community I would park on the outskirts and walk in. Then I would go door to door, ready to speak with anyone who was willing to have me. Over time I developed deep relationships with particular residents that would result in my interviewing them multiple times over a period of years in person, over the phone, over endless cups of sweet tea and in a few special occasions cans of Bud Light. These conversations were always two way streets with residents inquiring about me and my life just as often as I inquired about theirs. And from those long conversations, these deep engaugments, I learnt not just about the community and its changes but also the very language locals use to describe what was happening to them. So much of the writing in this book is the result of my learning to listen to those who sea level rise is touching now, learning to see the world from their perspective. The whole thing taught me, I think, a lot about the importance and limits of empathy. Marya Hornbacher, in “The World is Not Vague: Nonfiction and the Urgency of Facts,” writes that “The decisions we make about structure are ultimately decisions we make about meaning.” She also says that in nonfiction, particularly work that moves towards what we would consider more objective, it’s important to remember that in reading, we’re still reading a work in which the writer has shaped facts--and the context of those facts--for a specific purpose, in pursuit of a specific meaning. To your earlier point, are you aware of the specific choices you made to shape that meaning? Either on the large scale or the small scale? One of the things that makes Rising unique is the form of the book itself. Each of the nine chapters that are reported from different coastal communities around the country opens with a short essay written entirely in the voice of a resident of that community. This is a form of writing called “Testimony” and it has a long history reaching back to the contentious Native American Autobiographies recorded as the frontier closed to various activist groups throughout Latin America writing in the 60s, 70s, and 80s, to, more recently, Svetlana Alexievich and Francisco Cantú. Sometimes people describe this genre as one that is interested in “giving voice to the oppressed.” But I am skeptical of using the verb “to give” here. Oppressed peoples have voices of their own. I think of the testimonies here not as an example of my giving voice to oppressed peoples but rather my giving them a microphone. Which is to say, baked into the form of this book is a desire to make central voices often left on the margins. At the end of “Marsh at the End of the World,” you retell the Hindu fable about the flood and the reestablishing of the world and briefly considers the spirituality of flood stories, a relationship between religion and ecology. Later, you write of the biblical flood: “I do not believe in a vengeful God—if God exists at all—so I do not think of the flood as punishment for human sin. What interests me most is what happens to the story when I remove it from its religious framework: Noah’s flood is one of the most fully developed accounts of environmental change in ancient history. It tries to make sense of a cataclysmic earthbound event that happened long ago, before written language, before the domestication of horses, before the first Egyptian mummies and the rise of civilization in Crete. An event for which the teller clearly held humans responsible” (74). Nearly every civilization has a flood story—not a fire story or an ice story, but a flood story. What are we to make of that in the context of rising sea levels, or as the case right now in southern Minnesota in the last two weeks, flooding that would have been minimal, had the farmland not been tiled and the wetlands filled in? It might not be a coincidence that so many civilizations have flood stories. 15,000 years ago an event geologists call “Meltwater Pulse 1A” took place. Sea levels rose 50 feet over 300 years. 15,000 years ago human beings existed but we did not have written language. So sometimes I wonder if all the the stories of flooding that we have in our ancient texts are actually a human record of real events that profoundly reshaped how life at the water’s edge took place. The stories of these events may have been passed down orally, generation after generation, until by the time they finally appeared in print they had been twisted and transformed and polished over time so that they might today appear to us as myth. It’s interesting to think about the movement from truth into myth--especially as this book is working to make sea level rise real, beyond climate change deniers pretending it isn’t happening. In a sense, this book is working to reverse the myth of flood stories. I have never thought about it that way. In part because I think the idea that there is a clear line that separates truth from myth is misleading. These two kinds of sense-making rhetorical modes breathe into and inform one another. Many things that we think we know, definitively, are in flux. For instance the very rate at which sea levels are rising and our projections of just how high they will get by 2100 doubled in the time it took me to write the book. One of my favorite creative nonfiction books to explore this kind of thinking is John D’Agata’s The Lifespan of a Fact. The The Lifespan of a Fact is a strange book, at its heart is an essay written by John D’Agata about suicide in Las Vegas. Running in the margins around the text is the ongoing conversation that took place between John D’Agata and his fact-checker. The New York Times describes The Lifespan of a Fact as “less a book than a knock-down, drag-out fight between two tenacious combatants, over questions of truth, belief, history, myth, memory and forgetting.” So, you know, if you haven’t read it, drop everything and go read it now. You write, “Wetlands have long been viewed as wastelands. The Hippocratic writings that incorrectly link the stagnancy of the marshes’ waters to the production of phlegm echo in the cries of ‘Drain the swamp!’ ringing through the streets of Washington today. In the antebellum South, wetlands were thought to corrupt the air and whoever breathed it” (139). What happens when we give moral character to landscapes and the people who live on them? How have we come to create virtuous landscape as well as morally suspect landscapes, where pests, mosquitoes, and diseases live? In an era where climate change is profoundly impacting communities around the world those landscapes (and residents of them by extension) that we view as virtuous, or sublime, often receive more funding for adaptation, resilience and relocation while those that are labeled morally suspect, or worthless, are overlooked if not polluted further. As I mentioned earlier wetlands in post-contact North America were long viewed as wastelands. This is why as cities developed we often threw our trash in them. Some of the country’s biggest landfills are sited atop former wetlands. Freshkills Landfill on Staten Island in New York City is a prime example. But perhaps what is even more disturbing is that these low-lying areas (and the land adjacent to them) would, over time, transform into some of the least expensive land in otherwise overcrowded metropolitan areas which is why lower income residents and people of color have historically sought these areas out. The once soggy fringes of many of our cities have long provided cheap, if flood prone housing, to those who literally could not afford to live anywhere else. These are the places that have long flooded the most regularly and gotten the least help. When we carry this logic into the present it should come as no surprise then that while Lower Manhattan is being wrapped in landscaped berms that can “double as skate parks and pop up cafes” residents of Midland beach in Staten Island (also known as “The Forgotten Borough”) are expected to remove their shoes and wade through the water. I’m watching the flooding in southern Minnesota right now (Summer 2018), after a very wet couple of weeks of rain, and we’re just starting to have conversations in this state about the effect of filling in the wetlands, tiling fields, and that maybe doing so wasn’t the best idea. Wetland act as giant sponges. They are one of the best natural flood defenses we have. And across the United States, both on the coast and inland, we have spent the past two centuries draining and developing on top of wetlands. As we begin to really address climate change adaptation we need to consider the fact of the land first. What kind of ecosystem was in place before humans developed there and how might climate change exacerbate pre-existing conditions? These are the kinds of questions we need to ask in order to address the challenges of present and future of climate change. You also observed that “When Hurricane Sandy destroyed much of Oakwood, many residents decided they didn’t want to return. They chose to retreat instead. To watch what remained of their house get bulldozed. To walk away” (76). What happens when people move inland—towards the Midwest, towards the Ogallala Aquifer, towards a place where the 100th Meridian is moving east—how will our conversations about water evolve? What happens when migration continues to move inland towards other landscapes—like the Great Plains—that are not considered valuable? One of the reasons I think we need to start wrapping our minds around the idea that the water is rising and will continue to rise is because not only do we need to start to talk seriously about how we retreat from the coast in as equitable manner as possible we also need to think strategically about where we are going to retreat to. You mention Oakwood Beach, Staten Island in your question and to me Oakwood Beach is a really interesting example of managed retreat. After Sandy the state purchased and demolished over 600 homes in Staten Island with the goal of moving residents away from risk while helping the buffering wetlands to return. As is often the case with managed retreat, local municipal governments are afraid of losing tax base. New York City was no different. In order to try to retain residents they offered a 5% bonus on all sales to the state if the resident purchased another home in the five boroughs. I was just back out in Oakwood a few weeks ago and I met with three leaders of the buyout movement there. They estimated that 75% of residents who participated in the buyouts stayed on Staten Island. All three of the buyout leaders moved uphill on the Island (out of the floodplain) but they stayed close enough to maintain their connections to the community. We had lunch at the same old seafood joint they have been eating at for decades. So when we talk about retreating from the coast I think it is important to remember that the primary goal is to move away from risk. That can mean moving inland a mile, as long as where you relocate to is considerably higher topographically. But you are also right that some people will move further in and we need to think about how we can absorb these new populations in places like the midwest and inland Maine. Corollary question: You write, “…throughout Western history tidal wetlands were thought to be the homes of swamp serpents and marsh monsters, the boggy, slimy sources of malaria, disease and death. As such, they have long gone overlooked, which is why the research taking place out here in the Gulf of Maine is so important” (56). In what other ways do cultural traditions of place play a role in which landscape we consider to be of value, or of little value? We are more aware of landscapes of awe, of wonder. What are the landscapes of fear? Of disgust? How do we write about—and be advocates for—landscapes that have been ascribed these negative characteristics? When I realized that if I wanted to write a whole book about sea level rise I would have to spend a lot of time in wetlands I was bummed. I thought why can’t I write about the disappearance of the snowpack in the sierras and then do a whole heck of a lot of hiking and skiing instead? That thought literally occurred to me. But the deeper I delved into writing Rising the more I began to understand just how profoundly my ideas of what kinds of nature are worthy of attention and, as a result, care is a cultural construction. So my first bit of advice is to read against the grain. Ask yourself why do I value mountain peaks instead of prairies. Then dig into human history and come up with an answer. Make sure to not just read about places you would otherwise overlook, spend time there as well. In doing so I promise you will discover a whole host of beings equally worthy of your advocacy. One of my favorite books (and favorite writers) is Paul Gruchow, who wrote a book titled The Necessity of Empty Places, one of the first writers to do sustained work on the northern prairies. Other writers are doing work on the prairies (a place I find infinitely fascinating), but it makes me wonder what you think about the work of writing in the work of advocacy. I do think of writing as advocacy, as helping folks pay attention to and understand the changes that are taking place around them. I also think that it is no longer enough to simply call out the problem of climate change. If we writers want to consider ourselves activists we also need to present clear paths for engagement for our readers. This is one of the reasons that the Oakwood chapter is so important to me. It illustrates how one coastal community organized themselves to advocate for a just Sandy recovery. This chapter shows the power of grass-roots organizing and it also describes the ground work behind the movement so that other communities might follow Oakwood’s lead. Along these lines, I have recently been working with a group called Flood Forum USA. Flood Forum is a national coalition of flood survivors that helps people harmed by flooding from across the US get organized, heard and supported. I was wondering if you’d say more about this-- “the more I began to understand just how profoundly my ideas of what kinds of nature are worthy of attention and, as a result, care is a cultural construction.” How did that happen for you? How did you see the cultural construction underneath the view? I suppose this realization came about through experience first, through spending time in tidal wetlands. I was living in New York City when I began writing Rising. Living in the city was hard for me, I was always working towards the long weekends when I could flee and hike in the Catskills and Berkshires. But the deeper I got into this book the more that burning need began to dissipate. I was spending more and more time in wetlands and learning to connect to the more-than-human world they held. It was a revelation to me that I could get my “nature fix” in Oakwood Beach instead of burning gas to drive upstate. And from that experiential knowledge came a curiosity to try to understand how it was that wetlands haven’t been as highly regarded as other dynamic ecosystems in our culture. I dug into the history of the conservation and preservation movements, the history of land-use practices and environmental law, the history of indigenous displacement and maroon communities and how they ended up often living on the soggy fringes of this country. The reason we don’t tend to value wetlands is complicated and interesting and it is one of the threads that I tug on throughout Rising. We encounter the first of many outside voices in “On Gratitude,” “On Reckoning,” etc. While the interludes offer new voices, the effect also takes its cue from Montaigne, the acknowledged father of the essay, in its “On __” titling. Were you being deliberate in your nod to Montaigne? How did you craft each of these sections to offer a meditation into gratitude, reckoning, and more? What effect did you intend for these digressions to have across the whole of the book? Did you structure them to be an escalation of these interview stories, a rising of their own? I refer to each of the sections that you refer to as testimonies. These essays are written entirely in the voices of a coastal residents that are coming to terms with and reshaping their lives to the rising tides. They are the result of extensive interviewing that I mentioned earlier. Often I would interview a person multiple times, then I would transcribe and edit the entire interview, whittling away until I crafted a meditation on a particular theme written entirely in the voice of that resident. It was a really interesting process and deeply collaborative as I would ask the interviewees to comment on various drafts of the essays as I worked on shaping them. Taken together I like to think of the testimonies as a kind of polyphonic chorus rising from the water’s edge bearing witness to the changes that are already here. As for the nod to Montaigne, while I wasn’t thinking of it at the time I am sure some part of my subconscious was probably looking in that direction. In “On Opportunity,” Chris Brunet says, “I mean really we are talking about having to choose to move away from our ancestral home. I know a lot of people figure we would be celebrating, to be moving to firmer ground and all. But it’s not like I threw a party when I heard about the relocation. I’ll be leaving a place that has been home to my family for right under two hundred years. I go all the way back to the island’s namesake, Jean Charles Naquin” (163). In which ways do you see place influencing identity? Later, Rush writes, “I respect the connection Edison feels with Jean Charles. He doesn’t simply live on the island; he knows who he is, his very sense of self, is linked to the land where his entire life has taken place” (179). Jean Charles Naquin and his family would have been kicked out of Acadie (Nova Scotia) in the 18th century, which is how they got to Louisiana—and so there’s a history of not having a choice in leaving one’s home going on here. It’s always been decided by someone else for the people of this community. My own ancestral history is Acadian, though we were exiled to Maine and Massachusetts, not sent to Louisiana to become Cajun. It’s a subject of land and belonging that I’m very interested in. Beyond that, the Acadians are people of land and water, building dikes against the Bay of Fundy so they could farm the land—modifying a landscape so they could survive with it would have been something familiar. Did you encounter this as you wrote about this area. Wow, how interesting! I didn’t know that Acadians were dike-builders up there along the Bay of Fundy. You learn something new every day. As for the deep history of being forced from one’s home that is something I tried to tease out deliberately in the book. The residents of the Isle de Jean Charles are of mixed ancestry comprised of Acadian, Biloxi, Chitimacha, and Choctaw peoples, all groups that were forcibly removed from their land as colonial powers sought control over parts of the Americas. So when some of the folks say they don’t want someone from the outside coming onto their island and telling them where they have to move now that seas are rising, I get that. History has taught them to be skeptical of such interactions. One thing that surfaced again and again while writing this book is the idea that if we want people to begin to move away from risk the idea has to come from them. It cannot come from the top down, which is why I believe it is so important for us to begin to have a broad and energetic public conversation about retreat as a form of resilience. Without that retreat will end up being about forced removal and I think it is of utmost importance that we begin to move away from that narrative collectively. What is your sense of the best way to do that? You’re right—the idea of forced removal has an ugly history in our country and it is something we need to acknowledge happened and then avoid as this conversation continues. Since the publication of the book, have you seen grass roots work being done well in certain places? What has happened to this conversation since the book came out? One of the best ways to do this is through horizontal information sharing amongst and between low-lying communities already being impacted by flooding. If you are considering managed retreat yourself it is a lot more convincing to hear the story from someone who went through the process than it is to hear it from a FEMA officer. When I read from Rising in flood prone coastal communities I often read the Oakwood Beach chapter. And when I look out into the audience I see the gears turning in people’s minds. When the Q&A part of the presentation comes they often ask questions about whether retreat might be conceivable in their community and how they might go about advocating for it. I find those on-the-ground conversations to be deeply rewarding, and I hope, impactful. In this way, As far as getting the word out there that this option exists, a host of publications around the country have been covering Rising, from The Nation to Quartz to The Atlantic to The Los Angeles Review of Books. Everytime the book is written about retreat is mentioned in mainstream media as a viable and necessary form of climate change adaptation. In this way I think it is certainly making the conversation around retreat more public. Whether this will translate into public policy is far more difficult to track. In your Afterword, you reconsider the failure of language in a way related to how you began the book. You consider the environmental racism and environmental justice of the lack of federal disaster response to Hurricane Maria (257). But you do not end her book with concrete actions for the reader to undertake, no calls to action. What, then, do you want from readers as we close the book? In writing the book, I wanted to avoid giving a simple solution to the problem because there is no one-off solution. I also wanted to make sure I didn’t slip into that know-it-all tone that too often surrounds climate change communication, that takes the information and subsequent necessary actions as self-evident. This tone steals agency from the reader and I think impedes, rather than fosters, new climate change action. With all this in mind I wanted the book to do two things. I wanted it to create, on the page, a network of flood survivors. So often when I would carry out my interviews in coastal communities residents would tell me that they felt terribly alone with their plight, that they didn’t know of anyone else who had been through what they had been through. But as storms get stronger and tides higher more and more of us are discovering ourselves in their soggy shoes. Put another way, this book I hope can act as literary example of the coalition of flood survivors that Flood Forum USA is currently building. There is strength in numbers and so very many of us are, or will be in the not-too-distant-future, vulnerable to flooding. My second aim was for the book to jump-start the conversation around managed retreat. We need to think about retreat as an adaptation strategy and fund it as such for a number of reasons, chief among them if we want the more than fifty percent of endangered and threatened species that are wetlands dependent to make it into the next century. One of the dangers I see in this conversation is that only the coasts will be a part of the conversation, because those who are not immediately affected by sea level rise will not feel a need to participate. How do you envision involved the whole country in efforts to manage this issue? Just because you don’t live on the coast doesn’t mean sea level rise will not impact you. Our National Flood Insurance Program is over 30 billion dollars in debt. The funds raised through flood insurance alone cannot cover that debt. Which is to say that whenever we have a big hurricane or flood event US taxpayers across the country pay for the recovery. So right now all of us together are already footing the bill for higher tides and stronger storms. As these flooding events increase the cost of flood insurance will continue to rise. As flood insurance becomes more costly the value of coastal properties, of any property in the floodplain, drops. And as the coastal housing market slumps and, likely crashes, the effects of that rapid devaluation of coastal property will ripple outward likely causing a recession. So just because you don’t live on the coast doesn’t mean that rising seas isn’t already affecting you. We are all in this together and the sooner we realize it the better off we will be. Karen Babine is Assay's editor and the author of All the Wild Hungers: A Season of Cooking and Cancer and the award-winning essay collection Water and What We Know: Following the Roots of a Northern Life.

For Further Reading |