The Assay Interview Project: Helena Rho

February 1, 2023

|

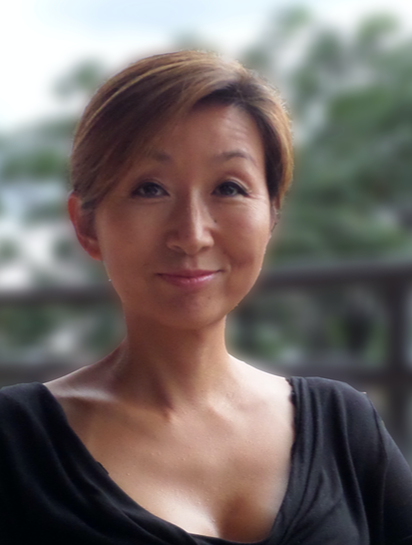

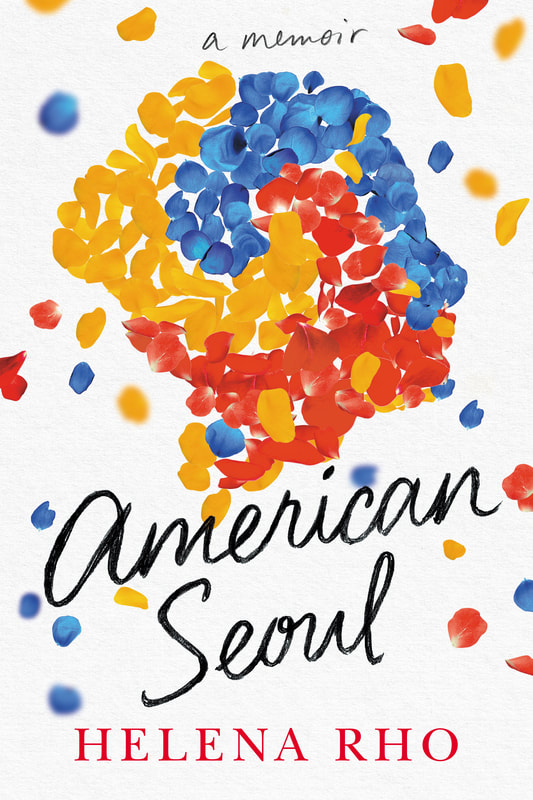

Helena Rho is a three-time Pushcart Prize-nominated writer whose work has appeared in numerous publications, including Slate, Sycamore Review, Solstice, Fourth Genre, 805 Lit + Art, among others. A former assistant professor of pediatrics, she has practiced and taught at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the Johns Hopkins Hospital, and the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. She earned her MFA in creative nonfiction from the University of Pittsburgh. American Seoul is her debut memoir.

|

|

About American Seoul: Helena Rho was six years old when her family left Seoul, Korea, for America and its opportunities. Years later, her Korean-ness behind her, Helena had everything a model minority was supposed to want: she was married to a white American doctor and had a beautiful home, two children, and a career as an assistant professor of pediatrics. For decades she fulfilled the expectations of others. All the while Helena kept silent about the traumas―both professional and personal―that left her anxious yet determined to escape. It would take a catastrophic event for Helena to abandon her career at the age of forty, recover her Korean identity, and set in motion a journey of self-discovery.

In her powerful and moving memoir, Helena Rho reveals the courage it took to break away from the path that was laid out for her, to assert her presence, and to discover the freedom and joy of finally being herself. Julie Marie Wade: It’s hard for me to believe that we first met nearly two decades ago, Helena, and harder still for me to believe that I’m now working with poets and creative nonfiction writers in an MFA program not unlike the program where we met. Large state university. Three-year course of full-time study. And in order to graduate, students must write and “defend” a book-length manuscript of poetry, fiction, or creative nonfiction.

Inevitably, in their second year, when graduate students receive their thesis director assignments, they have a lot of questions, but the one question that seems to undergird all the others is this: What makes a “good book” in my genre? It’s a question I struggle to answer without defaulting to the deeply unsatisfying “I know it when I read it.” So I’d like to start there. Before you wrote memoir, you were a reader of memoir, no doubt—a reader of literary nonfiction at large. What makes a “good memoir” in your mind? What are the elements of voice and craft that sustain you as a reader and that you seek to emulate in your own work in this genre? Helena Rho: Has it been that long since we met? No! Seriously, I’m still so grateful to the baby carrots you were munching on that day in Bruce Dobler’s class, which sparked a conversation and led to our friendship—it was fate! At least Koreans who believe in such things would say that, like me. And I love that you appropriate what Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said about pornography to adjudicate what makes a “good book.” Hilarious! I’m embarrassed to confess that I didn’t read a lot of memoir before I started my MFA in creative nonfiction—I’ve now read a ton! Metaphorically. When I first started reading in English at the age of six, in Uganda, East Africa, my parents couldn’t guide me because they weren’t fluent in any language other than their mother tongue, Korean. Of course, I’m not counting Japanese, which was the official language of Korea during the colonization of their country while they were growing up. Because my parents didn’t filter my reading, I read randomly and eclectically, whatever caught my eye in libraries and bookstores. I still do. I gravitated toward fiction, not nonfiction, in my reading before my MFA. But in hindsight, there were three books of literary nonfiction from those days that had a great impact on my memoir. Abraham Verghese’s My Own Country, his book about the AIDS epidemic in the heartland of America from the perspective of a doctor, gave me the first inkling that I could write about my patients. And that a memoir with a clear, reliable voice and clean prose about the people in a memoirist’s life could be fascinating. As a matter of fact, it was the patients, the cast of characters in Verghese’s book that I was drawn to, more than Verghese, the doctor. I’d also read Anne Lamott’s collection of essays Plan B, after George W. Bush was elected president, and I loved it. Lamott’s wit and wry humor helped sustain me during the long, miserable years of the Bush presidency. Her book also showed me how important humor is in writing. I’ve read and re-read her essay, “Ham of God,” and it still makes me laugh every single time. Amy Tan’s memoir, The Opposite of Fate, appealed to me because of the title. I still wonder, what is the opposite of fate? And after I read her book, I thought, “Wow. A memoir doesn’t have to be continuous!” A memoir can be a mosaic. Of course, after I enrolled in my MFA, I read many memoirs-in-essays. For instance, your Lambda Literary Award-winning memoir, Wishbone: A Memoir in Fractures! All of these nonfiction narratives have certain elements in common: a clear narrative voice and beautiful prose. All of these authors establish their authority and bend language in delightful and unexpected ways. I think I tried to emulate those elements in my memoir. Alas, I failed! I’m going to resist the urge to contradict you about that claim, and instead, to say simply, let’s talk about failure! I appreciate you invoking Wishbone as a touchstone memoir, but precisely because it is a memoir-in-essays, a mosaic approach to storytelling rather than a traditional, chronological arc, Wishbone might also be perceived as a failure. My own first encounters with memoir—and this has seemed to be true for many of my students as well—were books that served as the autobiographical analog to novels. Some version of: Author places herself as protagonist on the page and traces a series of personal conflicts and resolutions across a span of years to emerge triumphantly at the end as the hero of her own story. Despite all the books I’ve read that move differently—recursively, in segments, flashing-forward and flashing-back—my formative sense of memoir was essentially “write a novel of your own life as if you were writing the story of a character you’d created.” It took a while to shake the linear narrative imperative, but I’m happy to say that I want to keep “failing” at writing autobiographical novels so I can keep exploring new possibilities for making art and for deepening my understanding of my own life in the process. I’m guessing you know what I mean. American Seoul isn’t continuous. It doesn’t read as the literary analog to a novel. I’d like to know more about why you made the choices you did in structuring your book this way? Why were you drawn to the memoir-in-essays as opposed to, say, a sustained linear narration, when you began the process of writing American Seoul? Or did that decision come later in the process? And most especially, I’d like to know how you see the relationship between your aesthetic decisions in this book and the elements of personal growth/discovery they enabled. Failure? Please. You have over twelve books of memoir, poetry, essays, lyric essays published—there is no way on earth anyone could call you a failure, ok? But the motherfucking act of “failing” is important. As Samuel Beckett once said, “Try Again. Fail again. Fail Better.” I think the many iterations I went through with my memoir in over ten years of writing it was my version of failing better. And it’s funny that you say that traditional memoir is “the literary analog to a novel.” It’s because I didn’t think I could ever write a novel that I decided to pursue an MFA in creative nonfiction. I never intended to write a memoir. American Seoul started as one essay, “The Korean Woman.” I wrote the first version in 2005 because of an encounter with a Korean woman in The Strip District of Pittsburgh which nagged at me, bothered me, wouldn’t let me sleep. The question that haunted me was: Why didn’t I feel shame around this particular Korean woman? Because I’d always felt shame around my mother, a Korean woman. My mother was highly critical with insurmountable expectations for her daughters. Older Korean women are called ahjumma, and they are notorious for making younger people, especially young women, feel ashamed. But the woman in the Korean grocery store made me feel seen, like my existence mattered. So why would an encounter with a complete stranger make me feel this way? In order to figure out what happened, I had to write the essay. I think I’m the kind of writer who asks questions and not necessarily to find the answers. To quote Joan Didion: “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.” So American Seoul was pretty haphazard in how it came together. I had niggling questions which I had to write essays about to understand what had happened to me. In the case of “In Havana with Hemingway,” the funniest chapter of my memoir, the question was: Why was I compelled to go to Cuba? With “Parallel Universe,” which was supposed to be the last chapter of the memoir before my editor at Little A changed the narrative arc, it wasn’t so much a question but the fact that I woke up every day crying for a month after I’d returned from Seoul in 2006 that I needed to investigate. Well, I suppose, my question was “Why can’t I stop weeping about Korea?” So I started writing an essay, which wasn’t fully finished until 2016, and Crab Orchard Review published it. I’m still grateful to them because there was a long dry spell between me not writing for years during my divorce and me not submitting the things I’d already written. Their acceptance of my piece motivated me to finish my memoir. In writing American Seoul, I made the conscious decision that I wouldn’t write a sustained linear narrative. I’m not sure I know how to write straight chronology! I think time is fluid. Like memory. I love flashbacks. I love treating time as though you can enter parallel universes at the same time. But I structured my memoir like John McPhee advises writers to do with nonfiction narratives—what he used to call a backwards lower case “e” but now calls a spiral. Start at a dramatic moment in the story, most likely near the end or the middle, then go back to the beginning and complete your narrative arc. I started my memoir with a traumatic car accident that changed my life, then went back to my mother standing at a crossroad before I was born, continued with my father in an airport in Seoul when I was six years old, and then completed the rest of my story in a loosely chronological fashion with lots of time jumps, until my memoir ends with me in Seoul again. I share your love of flashbacks and the meaningful aesthetic challenge of depicting time in a way that matches our actual experience of it—how we carry the past with us into the present in the form of active and recurring memories as well as our speculations about the future, including wishes and fears. So writing the present, dramatizing the present really, of any time of life seems to me also a matter of writing the past that was informing that particular present and the future that was being conjured from it (anticipated, dreaded, both) all at once. Do you think this plurality of time is part of what draws you to essay collections specifically, not just the noun of “memory,” as in the root of “memoir,” but also the word “essay” as verb, “attempting” to wrangle time across its various dimensions? I’m a notoriously easily bored reader. I love reading several books at once. And I love essay collections because they allow you to jump around, you’re not too disoriented, and each essay is self-contained. Although a memoir-in-essays builds on each essay like chapters in a traditional memoir, it isn’t reliant on all the other essays in the book for meaning. Not only does a memoir-in-essays let you disdain time as linear with flashbacks and flashforwards, but you can experiment with voice. For example, I wrote chapters of my memoir from both my mother’s and my father’s points of view. I totally ripped off Maxine Hong Kingston in The Woman Warrior. Hong Kingston wrote a chapter of her memoir from the point of view of her dead aunt, a woman who’d drowned herself and her child, born out of wedlock, in the family’s well in China. This was a woman who Hong Kingston had never even met. So I thought, “Why not?” At least I knew my parents fairly well. And to imagine myself in their place was an act of empathy and compassion for me. In “Crossroad,” my mother faced a life changing decision, and the regret she felt afterward reverberated not just in her life, but in mine and my sisters. Likewise, in “The Last Jangsohn,” my father faced the consequence of disappointing his father and leaving Seoul but doing the right thing by his wife and daughters. Writing from their respective POVs helped me to feel closer to my parents and ultimately made me forgive them. The Woman Warrior is one of my favorite works of experimental memoir, which I hope Maxine Hong Kingston would find a favorable phrase. I certainly mean it as such! And I love the subtitle of her collection: Memoirs [plural!] of a Girlhood Among Ghosts. The chapter you mention, “No Name Woman,” is one I first encountered years ago in a literary anthology when I had just begun teaching, and at the time, I had no idea it belonged to a larger, single-author volume. The wonder of re-encountering it as a chapter within Kingston’s memoir enlarged my initial understanding of the both/and work an essay could do. You have published several essay-chapters from American Seoul in literary journals. What kinds of alterations did these essays require in order to stand fully alone and apart from your larger memoir? You also mentioned that your editor at Little A “changed the narrative arc” of your collection, and I’m curious as to what that process involved. Was it merely a matter of resequencing the essays you’d already written, or something more significant—asking you to write new essays to putty narrative gaps, removing essays or portions of essays to reduce overlapping content, or both? What do you see as the role of the unsaid in your memoir? Of memoirs more broadly? One of the challenges I find in writing essays intended to serve as chapters of a memoir and also free-standing works of creative nonfiction is how to avoid redundancy—or, better, how to find the precise line between redundancy (the reader’s heard this before in a different essay!) and recursion (the reader’s heard this before, but now it has taken on new meaning!) I guess in a sense, I’m talking about through-lines or even leitmotifs within a collection. What do you see as the through-lines/ leitmotifs of American Seoul? Did these emerge throughout the process of writing and revision, or did you always know what they were? If someone had asked you, “This book you’re writing—what’s it about?”, at what point would you have known how to answer that question? How has that answer changed over time? Since I stole Hong Kingston’s technique with POV, does that mean my memoir can be categorized as “experimental” too? Because I’d love that label! I think it’s vital to experiment with the art of memoir. What writers do at the margins is so important in expanding readers’ minds. I love memoirs that push the boundaries of what defines a memoir. Like The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch. Like Dictee by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. And I didn’t realize it until now, but I was actually ripping off your memoir, Wishbone: A Memoir in Fractures, in more than one way. You imagined your parents as a young woman and a young man and inhabited their POVs, right? Wow. “Third Door” is one of my favorite parts of any memoir in the English language. And did you know that for the longest time the subtitle of my book was: “A Fractured Memoir”? I love the idea of fracture and fractures. I thought that was the only thing I’d stolen from you, but I was wrong! Before American Seoul was sold as a memoir-in-essays, seven chapters were either published or about to be as stand-alone essays in literary journals. Some of them years before the book. And most of them were written or started during my MFA. So it was the reverse—I had to chisel down the published essays to fit into a more continuous narrative, as my editor at Little A wanted, for the book. Ironically, one of the most changed essays is “The Cranes,” which was published by Sycamore Review and nominated for a Pushcart Prize. I’m still kind of sad because “The Cranes” plays with time the most. Time is fluid in the original essay, like memory, like parallel universes. “Blue Petals on the Wall,” my chapter on domestic violence, originally appeared in Entropy online as “The Men in Medicine and the Theory of Evolution.” Unfortunately, it was slashed in half by my editor—she cut the part where I’d been repeatedly sexually harassed and assaulted by men in medicine. Since I didn’t want to call it “The Man in Medicine and the Theory of Evolution,”—and also, the part where I explained my theory of evolution was cut—we arrived at the new title for the chapter. American Seoul originally ended with “Parallel Universe” with me in Seoul in the summer of 2006. But my editor at Little A extended the arc of my book to include my divorce and my return to Seoul for the second time in 2019. I wrote eight new chapters including the prologue, which I suppose could be construed as “putty” to close “narrative gaps,” as you said. For instance, “Blood Flamingos in Uganda,” was written to close the narrative gap between me leaving Seoul and me starting medical school, and to give context to my history of sexual abuse as a child and the legacy of abuse that affected my son, Liam, in one of the final chapters of my memoir, “Legacy of Abuse.” The chapters that were eliminated from American Seoul were several “doctor essays” because I’d chosen a commercial press with Little A, and those essays were deemed “too esoteric.” Another chapter that was called “too literary” and cut from my memoir was “In Search of a Korean Cordelia.” I’m happy to report it was published in Cherry Tree last year as a stand-alone essay! I’m happy that my essay, which draws parallels between my mother and Shakespeare’s King Lear, is out in the world because I was told no one wanted to read about Shakespeare in a woman’s memoir when I was fighting with my editor to include it. I’m not sure a male writer would ever be told such a thing! One glaring leitmotif in American Seoul is grief. The grief of losing a homeland, a home, a family. The grief of losing childhood innocence, the grief of watching children die of illness, the grief of divorce, the grief of abuse. But I like to think there are also through-lines of joy and redemption and humor. I love dark humor, and I hope that comes through in my memoir. I like to think I’m a funny writer. I think it’s far better to laugh than cry at the tragedy of being human. You know, I was told I had to have an elevator pitch for my memoir, and I never got around to writing it. I still don’t have a concise answer about what my book is! I failed so miserably in writing “the jacket copy” of my memoir that my team at Little A came up with it—embarrassing, isn’t it? What writer can’t describe their own damn book? But I’ll say what I once said when asked about memoir: all good memoirs are really about the processing of grief. At the time, I was at a writer’s residency, and another writer who had written two memoirs immediately responded, “That’s not true!” Even after I offered examples of classic memoirs, critically acclaimed memoirs, best-selling memoirs. So, I’ve now modified my statement, “All good memoirs I care to read are about the processing of grief.” I hope people care to read American Seoul. Truthfully, Helena, I don’t know any writers who have written—at least to their publishers’ satisfaction!—the jacket copies for their books. Whenever I’m asked about elevator pitches or summarizing a memoir, I have to bite my tongue not to say what I’m thinking: “If I could pare down what this book is about in 1-2 sentences, I wouldn’t have had to write it!” Nonetheless, I think the jacket copy does capture something essential about the book, particularly these first two sentences: “She was everything everyone else wanted her to be. Until she followed her own path.” Not only in life, but in your approach to making the memoir itself. You followed your own path, and it led you here. What aesthetic and thematic challenges will you undertake next? What can we, your readers, look forward to? Thanks, Julie, for saying that I followed my own “path” in making my memoir! I consider it high praise coming from someone whose writings have and continue to expand the genre of what we call “memoir.” Give me a moment to sit with this, please! And as to what I’m doing next? I’m writing a novel. Who knew I’d write a novel? Not me. But in the middle of my divorce, when I thought I couldn’t go on—which seems very dramatic now!—a question popped into my head that I couldn’t seem to escape: “How does a person who has suffered unspeakable trauma go on living?” Several years prior I’d heard about the Korean victims of the Japanese Military sexual slavery—I’d thought about writing a long-form nonfiction piece, eventually. But the confluence in my mind of my suffering and those of the victims, who were mostly girls and as young as ten years of age, raped repeatedly, along with the generational trauma of Koreans from decades of subjugation and colonization by other nations, created a fiction opportunity. I heard the voice of a six year old girl (I swear I’m not schizophrenic!) who wanted me to tell the story of her sister, what the Japanese Imperial Army called “ianfu,” and where the misnomer “comfort women” came from and the surviving victims, who are now women in their eighties and nineties, disdain and refuse to be called—I had the honor of interviewing some of these surviving victims when I was in Korea in 2019. The Light of Stone Angels, the working title of my first novel, is the story of three Korean women spanning the time period from World War II to contemporary time. The main character is a Korean American woman, whom I’ve given some details from my life because I was too lazy to invent them, but whose life and story isn’t mine at all. It was so liberating to make shit up! Because it felt like I’d been driven crazy by my obsessive fact-checking in my memoir: “Did that person really say that? Am I really being fair to that person?” It turns out that I’m also suited to writing fiction—I love writing without boundaries. Julie Marie Wade is the author of 15 collections of poetry, prose, and hybrid forms, including Wishbone: A Memoir in Fractures, Small Fires, Postage Due: Poems & Prose Poems, When I Was Straight, SIX, Just an Ordinary Woman Breathing, and Skirted. With Denise Duhamel, she wrote The Unrhymables: Collaborations in Prose, and with Brenda Miller, Telephone: Essays in Two Voices. A winner of the Marie Alexander Poetry Series and the Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Memoir and the recipient of grants from the Kentucky Arts Council and the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund, Wade is an Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing in the undergraduate and graduate programs at Florida International University in Miami.

For Further Reading |