The Assay Interview Project: Kathryn Nuernberger

February 28, 2022

|

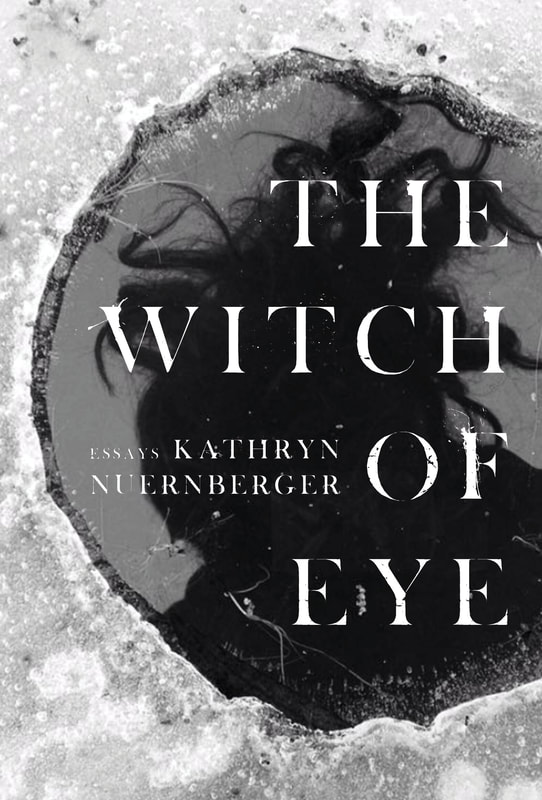

Kathryn Nuernberger is an essayist and poet who writes about the history of science and ideas, renegade women, plant medicines, and witches. Her latest book is The Witch of Eye, which is about witches and witch trials. She is also the author of the poetry collections, RUE, The End of Pink and Rag & Bone, as well as a collection of lyric essays, Brief Interviews with the Romantic Past. Her awards include the James Laughlin Prize from the Academy of American Poets, an NEA fellowship, and notable essays in the Best American series. She teaches poetry and nonfiction for the MFA program at University of Minnesota.

|

|

About The Witch of Eye: This amazingly wise and nimble collection investigates the horrors inflicted on so-called “witches” of the past. The Witch of Eye unearths salves, potions, and spells meant to heal, yet interpreted by inquisitors as evidence of evil. The author describes torture and forced confessions alongside accounts of gentleness of legendary midwives. In one essay about a trial, we learn through folklore that Jesus’s mother was a midwife who cured her own son’s rheumatism. In other essays there are subtle parallels to contemporary discourse around abortion and environmental destruction. Nuernberger weaves in her own experiences, too. There’s an ironic look at her own wedding, an uncomfortable visit to the Prague Museum of Torture, and an afternoon spent tearing out a garden in a mercurial fit. Her researched material is eye-opening, lively, and often funny. An absolutely thrilling collection.

Anna McAnnally: This is a book about witches, but this is also a book about, in places, etymology, love, salt, scarcity, narrative, ghosts, superstition, and so much more. In one of the more surprising turns, you discuss milk, saying, “The history of milk is a history of unexpected gifts and unexpected consequences.” Could you speak about how the journey of writing about witches lead you into so many other interesting spaces? What are some of the most surprising places that your research took you?

Kathryn Nuernberger: My experience with writing has been that way leads unto way. Before writing The Witch of Eye, I was working on a poetry collection, RUE, that featured a series of poems about plants historically used for birth control. While I had no trouble finding the names of plants that were “used to provoke the menses,” as the euphemism goes, I had a lot of difficulty figuring out whether I should be alluding to roots or leaves or stems or seeds in the poems. This knowledge, which was passed down by herbalists and midwives as part of an oral tradition, was largely excluded from written records or erased as part of larger campaigns of oppression. I knew many accused witches had been midwives and wondered if I might find these medical histories disguised in trial transcripts as confessions as or spells. They were not there – what I found instead was midwives being targeted because they were women with independent means and property, which could be fined away from them if they were found guilty of witchcraft. They were also people with power and influence in the community, which seemed to give inquisitors a bedeviled feeling. The most notorious of the accused were defiant and ingenious and pissed and I just couldn’t get enough of reading their testimonies. The challenge was that the testimonies were only recorded after the accused had been tortured or threatened with torture. Or the testimonies were only written down in loose summaries made by court reporters whose purpose was to justify the actions of the inquisitors. Even thought it’s a completely impossible thing to do, I wanted to try to represent these fierce resisting people in their own words, and also with fullness of their meanings, personalities, and intentions. This meant learning many fascinating things about their historical moments, geopolitical circumstances, and the relationships their communities would have had with the ideas of magic, spells, and the supernatural. At points in the book, you equate the devil to police brutality, the male gaze, capitalism, politics, and misogyny, while witches remain the brutalized victims of these forces. I enjoyed this flipping of the traditionally understood context -- it is not the witches who are communing with the devil; it is their persecutors. As you put it, it is the “judges” who put a “cruel spell” on the witches, not the other way around. You summarize this sentiment particularly poignantly near the end of the book: “how frightened the most secure people in our society are of the most vulnerable.” Talk about the journey of your research and writing and where you landed in the end. It was a real challenge for me, when reading these trial records, to get my modern head around the idea that every single person involved in these situations believed witches were real – the judges, the inquisitors, the kings, and the accused. I had been raised in a version of Catholicism that suggested believing there was such a thing as witches and that they had power at all was a form of paganism, a transgression. But there was once a time when everyone agreed that these evil beings existed, and the only question was whether or not you were one. Fully grasping these medieval ways of understanding the world required not only accepting that there are radically different ways of interpreting reality, but also realizing how much our individual senses of what is true and possible is shaped by the stories other people tell us about what is true and possible. Believing in scientific evidence, data, and double-blind studies, for many people, is the result of living immersed in communities that tell a particular kind of story that celebrates this way of knowing as particularly valuable. If you live in a community that instead immerses itself in a narrative about power and trust that puts Donald Trump on a pedestal, well, your odds of getting Covid and not understanding how or why that happened to you are probably going to go way up. But look, the stories we tell ourselves change all the time. And they change largely in response to which version of reality best serves our own self-interest. I don’t love that about humans, I wish it were otherwise, but this is the pattern I began to see as I read trial after trial, atrocity after atrocity. When rich white people started accusing other rich white people in Salem, suddenly the governor of Massachusetts declared that “spectral evidence,” which had long been a crucial element of witch trials, didn’t make any logical sense anymore. When it was impoverished white widows accusing the enslaved woman Titiba or the enslaved man known as John Indian, it wasn’t a problem for anyone in power. It was only after the governor’s wife had been accused of witchcraft that the whole idea of a witch suddenly became unthinkable, irrational, foolish magical thinking. There is no shortage of clever people who understand what a story is and how it works. I wish I could say these are the people who become writers, but in general, I think these are the people who become politicians, or even worse, campaign managers, or perhaps worst of all, pundits. As I was reading, I was on the lookout for people who understood they were in a story. Often it was the accused who came to that understanding, and sometimes they could use that understanding to figure out a “right” confession that would let them get out of their predicament alive. Other times they used that understanding to create a defiant confession, to put a hex on the crowd, or otherwise make people sorry they’d put such a person in the ground. But equally often it is clear to me that the judge or the inquisitor or the king or whoever it is running the trial knows or at least could easily understand the cruelty they are putting into the world if they cared to try. But instead they choose to look the other way because they like the way the narrative they are in benefits them. And I think the word for that is “evil.” The word they themselves chose for “exercising one’s power to cause harm” was “witch,” so I also sometimes call them that, in the hopes that they might understand themselves more clearly. When reading about witch trials, I have found that authors and scholars often dismiss the concept of witchcraft entirely. They conclude simply that, since witches are not real, the witch trials were unjust. Your approach here is different. You succeed in discussing the injustice of the witch trials while still making space for the possibility of the existence and practice of witchcraft. Can you talk about this perspective and approach to the theme of witchcraft both then and now? If you dismiss the concept of witchcraft entirely it is impossible to understand the people caught up in the witch trials and those who inflicted them on others. I really wanted to understand who the accused were and I think the first step in understanding is to believe people when they try to tell you the truth of their lives. I would add that I, like anybody, am surrounded by people who believe things I do not believe. Sometimes I love them and want to love them better, so I have to practice looking at the world as they do in order to show them the care I want them to feel. Sometimes I am frightened of them and their political power and influence, so I have to practice looking at the world as they see it so I can protect myself and others as best I can. Sometimes I think that their description of what they believe and the world they see sounds beautiful and hopeful to me and I wonder if I could believe it if only I tried, so I do try. As your title, The Witch of Eye, suggests, eyes and seeing, or rather not seeing, play a central role in the book. You grapple here with what is seen, what is unseen, and what relationship seeing has to the truth-seeking. How do you navigate your sense of responsibility to your subjects, especially in light of their woeful misrepresentation by historical texts you consulted in your research? I do want to see the accused as fully as possible, despite the ways they have been misrepresented and scapegoated by those who benefit from seeing them as villainous. To do that, I tried to use methods associated with sub-altern approaches to historiography. By that, I mean I was on the lookout for evidence in the historical records of the lives of the marginalized, the impoverished, the erased, and the overlooked. What could be learned from studying the spells or songs or fairy tales passed down via an oral tradition, only recorded in snippets after centuries? What can be gleaned about by our ancestors by investigating the archaeological evidence in trash heaps? What truths reveal themselves if you read a trial transcript against the grain, assuming the accused are telling their truth while the judges and prosecutors are the ones with forked tongues? And I also wanted to be clear-eyed about our own moment in history. Could we who inherited early modern European criminal justice systems have really changed so much? I don’t want to presume that I would be so noble or brave or prepared to resist an inquisition if it set up shop in my town. In fact, we’ve all learned something in recent years of what kind of people we would be, what kind of people we are, when a tyrant starts casting accusations to shore up his base and secure his power. And we’ve also learned what kind of people we are when a few deputized authorities take it upon themselves to first target vulnerable members of our communities and then conduct extrajudicial executions. But more than pointing a finger at others, I wanted to see myself clearly in this book, my desires and foibles and moments of bravery and moments of complicity or cowardice. I turn my eye inward not because I think I am or should be the center of anything, but simply because I believe we really only have our own stories to tell with any certainty, all the rest is speculation and wishing. If there was one woman who you discuss in the book whom you could interview, which one would it be? Titiba of Salem is one of the only accused who makes it out of her witch trial alive and with her integrity intact. She never accuses anyone who hasn’t already been accused by others. That’s almost unheard of in a witch trial – eventually everybody succumbs to the torture and points a finger at somebody else. Titiba does not. Instead she tells an amazing story about nameless faceless people wearing the clothes of the wealthy somewhere near Boston who haunt her dreams. She describes a little yellow bird, she describes plants, she describes angelic and demonic beings in a whirlwind. She offers the people of Salem a chance to end their witch trial right then and there, by concluding they cannot know who these wealthy witches near Boston are, but thank God the Rev. Parish’s daughters seem to be alright now. These slaveholding villagers who imagined themselves somehow more human than Titiba declined the merciful out she gave them. Instead, they turned on each other and began flinging accusations wildly in all directions. They even forgot Titiba was there for a while. She suffered a terrible winter in their jail waiting for the trials to end, but when they were over, she was alive. And I’d like to talk to her about how many of her choices were planned, how much she was able to see coming, how intentionally she wielded the power of her stories. I’d like to figure out how those of us who would like to work a little magic on our own chaotic and maddening leadership might be as effective as she was. And I’d like to know whether she and her daughter, Violet, were ever able to be together again. Knowing what I do of slavery and history and the records about her that exist, I suspect the answer is no and it breaks my heart. But I’d like to be able to ask her the question, because what if the answer could in fact be yes, they were together and yes, they were happy, and that joy just happened beyond the edge of some page. Anna McAnnally is a second year Ph.D. student at the University of Missouri, Columbia, where she specializes in 19th century American literature

For Further Reading |