The Assay Interview Project: Kerri Arsenault

January 24, 2022

|

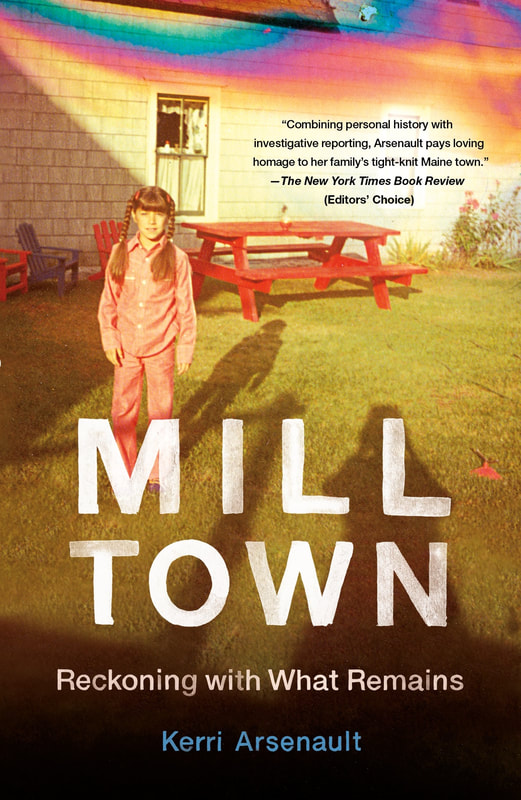

Kerri Arsenault is a book critic, teacher, contributing editor at Orion Magazine, nonfiction editor at the Franco-American journal, Résonance, and the author of the best-selling book, Mill Town: Reckoning with What Remains, which won the Rachel Carson Environment Book Award from the Society of Environmental Journalists and the Maine Literary Award for nonfiction. Her work has appeared in Freeman’s, the Boston Globe, Down East, the Paris Review, the New York Review of Books, and the Washington Post. She has also served on the National Book Critics Circle board for four years and has held 86 jobs. Starting January 2022, she will be an Associate of the Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard. Find Kerri online on her website, on Twitter: @KerriArsenault, on Facebook, or on Instagram: @kerriarsenault.

|

|

About Mill Town: Reckoning with What Remains: In sharp and inquisitive prose, Kerri Arsenault’s Mill Town: Reckoning with What Remains asks a question that is nearly impossible to scientifically and thus definitively resolve—is the paper mill in her small hometown of Mexico, Maine to blame for the town’s high rate of deaths by cancer? Arsenault sets out to get to answer this question anyway. She maps her family’s ancestral Acadian roots over regional histories to reveal how the impacts of industry, for better or for worse, all add up: as bioaccumulated toxics in our bodies, as sludge in the rivers, as identity and culture in the very fabrics of our towns, as well as in our own families and personal narratives. The knots of relation, loss, love, and family get knottier and snarl on each new fact. “Sometimes,” Arsenault writes towards the end, “there’s no clear answer to the riddle at all” (297).

Caylin Capra-Thomas: Mill Town is a text concerned not only with place (that is, Mexico, Maine, the mill town in question) but also with mapping, whether those maps chart the familiar paths we make with our habitual comings and goings or those we must carve on our own to leave home. You map lines that connect people to each other, to ancestors, and to place. Your text is as much about what is visible in these maps as it is about what is invisible, and maps, in general, say as much in what they leave out as they do in what they feature. What other kinds of non-geographical maps would you make if you could?

I always held close the framework and mechanisms of genograms, which are similar to a family tree but also show patterns that may influence how we behave, like conflicts, traits, education, social relationships, divorce, behavior, illness, occupation, events, disease, alliances, and so on. These connections can reveal things beyond timelines or simple family trees. Many reviews have noted that, while broadly nonfiction, Mill Town elides or blends the genres of memoir and investigative reporting. I loved learning that you even consulted poets to write Mill Town. (Confession: the poet in me must know more!) Beyond writing about how Longfellow’s “Evangeline” misrepresents Acadia and Acadian history, what other poets or poems informed the making of this text and how? And more broadly, what was your experience with the slippery (hopefully not dioxin-laden) fish of genre while writing Mill Town? I’m thinking here, too, about other-artistic mediums beyond literature—the many photos you took while researching, and something like a syllabus of film and television, music, and visual art that influenced, shaped, or became important as you were writing. There wasn’t any particular poet or collection I felt directly influenced by except for maybe A Certain Clarity by Lawrence Joseph because he writes about the working class, capitalism and its discontents, politics, poverty, and love, and John Freeman’s Maps, which examines the effects of landscape and place. Poetry’s distillation of ideas, attention to words, and compression of emotion is what informs my writing. On my desk now? Shrapnel Maps by Philip Metres, Oculus by Sally Wen Mao, Unaccompanied by Javier Zamora, and Lessons on Expulsion by Erika L. Sanchez. Two books contain the word “map,” which I attribute to my obsession with the lines that divide and contain us. In addition to memoir and investigative reporting, I also see my book as a cultural criticism, because I investigate history itself: how we record it, how we archive it, how we teach it, who or what is memorialized and how, what remains invisible or visible, and who gets to decide all of the above. Part of the responsibility of being a kind of critic is to be informed about many things—film, TV, movies, music, photography, the general news stream, ideas, books. So, these things are not just flotsam and jetsam, but became part of the book itself. In Mill Town’s chapter titled “Buried in Paper,” you list the myriad kinds of sources from which you gathered information: “…I gathered information from historical societies, academic journals, the EPA, experts, legal briefs, sociological studies, poets, environmental historians, lobbyists, courts, lawyers, news articles, chemists, death certificates, and took thousands of photographs” (284). The buildup of source material begins to feel as weighty as that of the text’s other forms of accumulation. You have mentioned in other talks and interviews the many methods and tools you used to wrangle these materials into a book. I’m now curious as to the lifespan of artifacts and ephemera after the book. Where have they gone, and how might they factor into future projects? My research lies mostly dormant in a trunk in my office, in a zillion files on my computer, and in boxes in my attic. But I’m about to revisit it because the new project I’m working on may require some of the same research. I’ll probably never throw it away because it took me so long to gather. I accumulated information like our river accumulated debris, like my DNA accumulated toxics spewed from the mill, like we all accumulate identity. I was so impressed with your well-balanced and multidimensional portraiture throughout the text. Every character is fully human, including yourself, and while this knowledge can be fraught or vexing, the text shows us that sitting within the murkiness of others is a normal part of how we live and get by. My favorite example of this is in the chapter “Hope Springs Eternal,” at a Water District meeting whose agenda includes discussing whether to let Nestlé bottle water from Rumford Water District for Poland Springs. Here we are introduced to Jolene Lovejoy, a trustee of the Water District, who you describe as having “served the town for many years as a scrappy, surefooted Republican” in many various positions. You and she are clearly at odds on this particular issue, and probably many others, but the interaction between the two of you after the meeting does so well in casting her as someone who is both an adversary and maybe someone who is worthy of that position: She’s trim and perky and her short white hair shows off her tan. Jolene lives down the street from my mother, suffers no fools. Which I kind of like. We live in highly polarized times, and as you write in “What Goes Up Must Come Down,” “Humans generally prefer unambiguous situations” (45). How did you develop your ability to get beyond the notion of good guys and bad guys to navigate the muddy waters of human personalities? How should writers engage multidimensionality when their subjects are, whether because of death or distance, less known to them, and the record only contains their sins or good deeds?

One, stop talking and listen. Not just what comes out of people’s mouths, but what’s also between the lines of what they are saying or what they are not saying. Two, did I say listen? It’s a component of conversation most people forget. We all spend too much time arguing and opining and trying to convince people that what we believe is the correct thing to believe. That’s not a conversation. That’s just being a jerk. Also, if you listen, you will get to know that person and may find different sorts of alignments. I feel like our society has forgotten the tender notion of respect, which goes hand-in-hand with listening. Three, people are complex! People have the capacity to change! People can be two or three things at once that don’t agree with our binary designs! People should not be defined by one thing, like a political party or an opinion on abortion. These things are not concepts I had to force myself to consider. This is how I think. Is there any writing advice that you’ve heard frequently, whether given to yourself or to other writers, that you think is bogus or unhelpful? Based on the issue you think the advice is meant to address, what would you suggest instead? The best “writing advice” is to not adhere to too much “writing advice” but rather read…and read deeply. When I want to write beautiful sentences, I read beautiful sentences. Caylin Capra-Thomas is the author of the poetry collection Iguana Iguana, forthcoming from Deep Vellum Press. Her work has appeared in journals including New England Review, Pleiades, Copper Nickel, Colorado Review, 32 Poems, and others. The recipient of fellowships and residencies from the Vermont Studio Center and The Studios of Key West, she was the 2018-2020 poet-in-residence at Idyllwild Arts Academy and now lives in Columbia, Missouri, where she is pursuing a PhD in English and creative writing at Mizzou.

For Further Reading |