The Assay Interview Project: Madhushree Ghosh

May 12, 2023

|

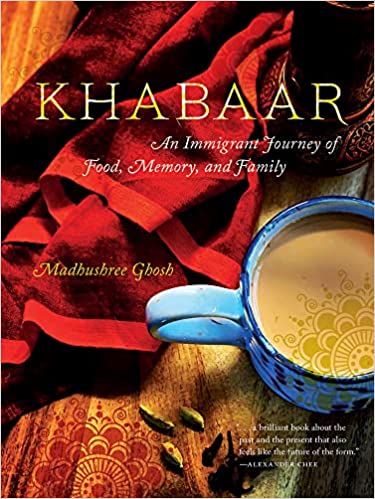

About Khabaar: An Immigrant Journey of Food, Memory, and Family: Khabaar is a food memoir and personal narrative that braids the global journeys of South Asian food through immigration, migration, and indenture. Focusing on chefs, home cooks, and food stall owners, the book questions what it means to belong and what does belonging in a new place look like in the foods carried over from the old country? These questions are integral to the author’s own immigrant journey to America as a daughter of Indian refugees (from what’s now Bangladesh to India during the 1947 Partition of India); as a woman of color in science; as a woman who left an abusive marriage; and as a woman who keeps her parents’ memory alive through her Bengali food.

Madhushree Ghosh is a woman of science. She has a PhD in biochemistry and a postdoctoral fellowship from Johns Hopkins University. She is an activist and a reader. She is a supporter of good food and good words, especially if they contribute toward making our world fair and interesting and shine a light on people thus far not in the limelight. Madhushree also does not suffer fools. I say this despite having never met her in person but because we have now been friends on social media for a number of years.

My favorite detail about Madhushree, however, is her generosity. In spring 2021, I invited her to be a guest in my grad class on Food Writing. Madhushree “Zoom-ed” in to our class in Wilmington, North Carolina, from her home in San Diego, California; read from this fantastic essay, assigned an in-class writing exercise, and answered a variety of questions. When a student asked her for advice on how to put together a proposal for a creative nonfiction book centered on food, Madhushree answered in detail and later, once class ended, she emailed me her proposal so I might share it with everyone. No questions asked. In nearly fifteen years of teaching creative writing, I always hear writers and writing teachers talk about generosity. I have seen it in action too, quite a few times, and Madhushree’s gesture easily ranks in my top five. Luckily for us, Madhushree has published a memoir: Khabaar: An Immigrant Journey of Food, Memory and Family. She takes us to places as diverse as Singapore and India, Maryland and California. Luis Alberto Urrea calls her book “unforgettable.” I couldn’t agree more. Sayantani Dasgupta: You mention in the book that you don’t come from a demonstrative family. What kinds of mental gymnastics did you have to do in order to write this deeply intimate book? Was it ever tempting to turn your life stories into fiction instead and pretend that all this happened to someone else? Madhushree Ghosh: To be a demonstrative person in a non-demonstrative family is and has been sheer hell. I didn’t know that was the issue, because it’s not that the Ghosh family wasn’t passionate or emotional. We had all-out political discourses at the dining table, constructive arguments about social justice, but we ran away any time a hug was coming our way. I know Ma would hug me when I was a child and Baba would lift me up onto his shoulders every evening when he returned from work. But as my sister and I grew up, these became—for obvious practical reasons—few and far between. Hugs were for children, and we suddenly became young adults and then adults. “I love you” was a Bollywood ‘filmy’ term, most certainly a very western one. That never happened in the Ghosh family. All this to say, expression of personal love and emotion for each other was cringeworthy and hence to be avoided at all costs. And yet, here I was, the baby of the family, ready to hug and be hugged. It was only when I came to America, where physical expressions of love between family, friends and lovers was casual, usual and frequent, that I realized this felt right. This was me. So, whenever I went back home, I hugged my mother tightly and she complained though she smiled when I did. I squeezed my sister and she offered me awkward side hugs. I was and remain a Ghosh outlier daughter. Writing Khabaar was a whole lot of emotional curtain removal of the personal. I was careful to make sure my very private sister’s life wasn’t exposed and respected my now-dead parents in how and what I presented them. You are absolutely right—whether you write fiction or nonfiction, what you finally put on the page are characters and you can be very objective and practical about what is shared. One can talk about tender emotional aspects of one’s life without giving away everything that one holds dear and personal. The epigraph in your book is a quote by Arundhati Roy from her book My Seditious Heart. Could you speak to that? What is the role of politics and activism in your writing? I know you care deeply about issues of appropriation, colonization, and privilege. Do you think it’s every writer’s duty to bring in a strain of political questioning into their writing? While everyone I have interacted with understands Roy through her fiction, she has been my role model in her fearless activism. Writing for her is a tool to engage in social justice and her nonfiction shows. She may be problematic to some, strident, naïve and passionate to others, but as a social justice activist, her words hold her essence and I respect how she lives that life when frankly, she had such tremendously easier choices she could have easily gravitated to. The epigraph is “Another world is not only possible, she’s on her way. Maybe many of us won’t be here to greet her, but on a quiet day, if I listen very carefully, I can hear her breathing.” This in essence is what activism is about—as a writer, what we have are our thoughts and how we translate them to words that then translate into action. I come from a privileged middle-class Indian family—I did not want for anything, and my parents were progressive while traditional who were literary, politically-conscious and very aware of how they navigated their refugee status into middle-class lives. It is easy to then do the ‘crab in a bucket’ syndrome and say, “Well, we did it, so others can too.” Or, or, or, how about we look at it from the perspective of, well, perhaps there’s a reason why the underprivileged or the caste system may not be allowing some of us to get the same opportunities. Coming from India, where the country was three countries now divided by the colonizers, to not talk about colonization would be like saying I don’t need air to breathe. We have the privilege, us writers, that we have words we can use effectively. We have the ability to see social justice in action and in inaction. I choose to not shut up. That is not to say other authors will choose the same path—after all, if we are looking for freedom of expression, you can do whatever you want. But I ask you, you the writer, what made you want to write and if it was to express, why wouldn’t you do it to make this world better than how you found it? It—to me—is very obvious. Having lived in the U.S. for so long, do you worry that your gaze or worldview as a writer and as a person may have become more American? That you may have lost your Indian-ness? I would love to know what you think you have gained and or lost in the process of making a home here. I have lived in the US longer than in India and yes, that worldview as a writer is an interesting one. I’ve been told that you are pretty much stuck in the decade you left India—for me it is the nineties. I’m still unfamiliar with new customs in India. For example, we have to apparently stand up in movie theaters as the national anthem plays while we balance our popcorn and chai—what does patriotism have to do with popcorn in a darkened air-conditioned movie theater? Or, that open air markets have now been replaced by plastic-ensconced milk and vegetables. India is now more western in many aspects than where I currently live, in my opinion. Living in America gives me the luxury to get access to the stories of global immigrants and refugees, a platform to discuss these issues without ramifications of being sued, or jailed or worse, and also, whether it’s an immigrant or a country—we aren’t static. We change, we adjust, we morph and we evolve. To answer your question, I don’t know what my ‘Indian ness’ represents—is it a love for where we came from? Or is it what “Desi” means? Or whether what I am is what being Indian and American is. It’s a fascinating journey and I am here for all of it—even the loss of the Indian accent, the roll of the ‘r’s to me is an evolution, a change and this too is what being an Indian in America is. Do you read, think, or dream in any other language besides English? How do they impact how you write? Yes, I do actually—Hindi, Bengali and to an extent, Bollywood (which is a separate language in my opinion). I think being Desi is a state of being. The way we think, the imaginative methods we employ to tackle universal problems is very different from the western gaze and perspective. Yes, it affects how I write—not only in the fantastical elements that come naturally in this sort of writing, but in the introspective nature of the work. I personally love the big, bold, brash world of Bollywood and some of my writing, especially when describing conflict reflects that. When I translate my dream/imaginative ideas into words, using such flourishes are but natural to me. Add to that a dry sense of humor, makes it an interesting way to looking at age-old problems like patriarchy, social injustice or plain-old misogyny. I believe you entered the world of creative nonfiction and memoir long after you had successfully established yourself in your chosen professional field. How did this empower and or hinder your abilities as a writer? I ask this because the term “imposter syndrome” comes up a lot in writing classes and workshops. I ask this question specifically because I often find students grappling with issues such as, how does one stay a writer and continue to have faith in one’s writing when it seems everyone else is getting published but not them. Establishing myself as an executive within biotech, medical devices and oncology diagnostics was actually to my advantage as a writer. I was able to talk about that world without minimizing writing and vice-versa. This also led to other emerging women in science to acknowledge that they could have a life outside of science and still be good scientists. Imposter syndrome however, is a different story—as a woman of color coming from a patriarchal world and entering a white world of science, misogyny is part of the career minefield. And then to add to this, the prospect of trying to be a creative writer is ‘icing’ (not) on this proverbial cake. It was an advantage not to be a young writer—and by that I mean, it was okay not to be a successful writer while I established myself as a scientific leader. Of course I struggled to be a writer—but what being a scientific leader meant was that I didn’t question that I could get into a ‘new’ field and establish myself as I worked hard at it. Does this mean I don’t question myself and my ability as a writer? Absolutely not—that kind of angst comes with the writing life territory. But acknowledging one’s ability to be good in using both parts of one’s brain is half the battle won. But imposter syndrome as a writer is a different ballgame altogether. What you’re talking about is writer envy. I wish we could—as teachers and elders—start showing younger writers, ways to continue to work on writing without competing. What I write is different from what you do. Also, if I cheer you on your successes and you do mine, we both win. The pie is large and the rising tide lifts all boats—I say this because it needs to be said. I say this because it’s true. To be a writer is a lifelong struggle. Adding envy to it alongside imposter syndrome are issues we can easily sidestep if our teachers, supporters and mentors continue to reiterate why competition has no place in the writing life. The cover photo and several of the other photos in the book have been taken by you. What was your vision for the cover? What determined the pictures you selected? What do you want the reader to take away from them? The cover photo—that of Darjeeling tea in my favorite cup next to a sari fabric from Suta Saris (a woman owned business from Kolkata, run by two feisty feminist sisters) had huge significance to me. Throughout my reading and writing life, I came across the “Indian” paisleys, earth tones, a sad Indian/South Asian woman’s profile, long hair or the focus on spices, spice boxes and what was and continues to be considered Indian lit. I had promised myself I wouldn’t do that, because we Indians are all that and we are not and we are more. The tea image was a reflection of what it is to be Indian, but really, tea wasn’t indigenous to India. It was brought in by the colonizing British from China to Assam and Darjeeling to enable a tea trade to bring to London/UK as good from their colonies that was cheaper than green tea from China. Masala chai is what happened to tea when the British sold it to Indians who were used to spices and sweet beverages. The image reflects what colonization means to us Indians. Where we believe chai comes from India. Which is does and it doesn’t and also is a reflection of colonization. The sari fabric while very Desi, is a reflection of the textile industry in India that is dying and now reviving due to the entrepreneurial efforts of women like those who run Suta Saris who market these affordable designer saris to contemporary Indian (and South Asian) women as wearable, sustainable, organic art. That in essence is what I wanted the cover to show—that India isn’t just spice and tea. And the tea you drink and see represents many other aspects of Indian history you, the reader, may not be aware of. The other pictures in the book are dishes I’ve made, mainly during the pandemic and I had enough time to devote to cooking. During the pandemic I was also unable to write as much as I used to. I channeled my creative energies to taking photos of what I cooked. Each dish either represents some aspect of my life, or that of the general world of immigrant foods. That’s what I want readers to take from each dish photographed. There are multiple stories in each image—whether it’s the coconut naru from my childhood that I now make in San Diego, a Punjabi kadhi with pakoras in turmeric-soaked yogurt or a fish curry Ma used to make when we lived in Chittaranjan Park, South Delhi in the seventies and eighties or the curry I now make in Ma’s memory. Each photo, each dish, has more than one story. What do you pay attention to as a writer when reading works by other writers? What techniques have you borrowed and from whom? I love the first paragraphs of narrative nonfiction, especially of writers of color. The start of an essay or a memoir tells you the journey they will take me on. For example, Grace M. Cho’s Tastes Like War (The Feminist Press, 2021) starts with, “I am five years old, walking down Main Street with my family. The usually sleepy downtown is a riot of balloons and streamers, a marching band thunders past. “It’s America’s two hundredth birthday,” says an old lady with short curls as she hands me a re-white-and-blue popsicle. Funny to have a birthday party for a country, I think and yet I am far too young to consider what it means to be patriotic, or American, or Asian in America.” To me, therein lies the struggle of the author of where she fits in, what is America and who is she. We—writers of color—tell stories that are more like tales. Which is to say, it’s imaginative, expanding and highlights a world the reader may think they know but would like to go on that journey with us. That’s what I love about memoirs by authors of color. Of course, the reportage style of Eula Biss, the detailed research by Suchitra Vijayan, the description of grief of losing her husband during COVID by Jesmyn Ward are all techniques that pull us into the story without losing the arc or the ultimate crux of what it means to be a writer. I enjoy these styles as well as understanding the braided narrative ways to describe complex perspectives like Jo Ann Beard in addition to Mayukh Sen and Sharanya Deepak’s styles of what we talk about when we talk about food, especially in South Asian worlds. Now that your first book is out in the world, what is your relationship with it? Do you feel protective given so many of the memories are of your parents who you write about with great affection and admiration? While this may be my first book, I have eight other manuscripts on my hard drive, so it doesn’t feel like it’s my first one, to be frank. I am grateful and humbled by the love this has received, and for the number of readers who have connected with it and reached out since it was released in April. I still have an out-of-body experience-like emotion about it when readers talk about it. It feels like they are talking about someone else and then I have to shake myself back out of that imposter syndrome. I also feel and this is what my writing mentor Dani Shapiro has said about what happens once a book is out in the world. I gave you what I think is my heart. What you do with it, as a reader, is your choice. My heart remains that, my heart. So yes, it’s a love letter to my parents. It will remain so. But I cannot expect everyone to read it with the tenderness and love I wrote it with. I can only hope you see the joy my family has brought me and I can only hope you too appreciate and enjoy that life and world with me. Born in Calcutta and raised in New Delhi, Sayantani Dasgupta is the author of the upcoming essay collection Brown Women Have Everything. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Idaho. Her essay “Rinse, Repeat” was named a Notable Essay of 2022 by Best American Essays. Previous books include the short story collection Women Who Misbehave, the chapbook The House of Nails: Memories of a New Delhi Childhood, and Fire Girl: Essays on India, America, & the In-Between, a Finalist for the Foreword Indies Awards for Creative Nonfiction. She has been awarded a Centrum Foundation Fellowship, a Pushcart Prize Special Mention, and the WILMA Woman of the Year award in Arts for 2022. She is a contributing editor for Assay: A Journal of Creative Nonfiction and the founder of Write Wilmington. Her research interests include Creative Nonfiction, Literary Fiction, South Asian History and Literature, Indian Cinema, World Religions, Fairy Tales, Folk Lore and Mythology. An Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at UNC Wilmington, Sayantani has also taught writing in India, Italy, Colombia, and Mexico. She is a Contributing Editor at Assay.

For Further Reading |