The Assay Interview Project: Maggie Paxson

January 25, 2021

|

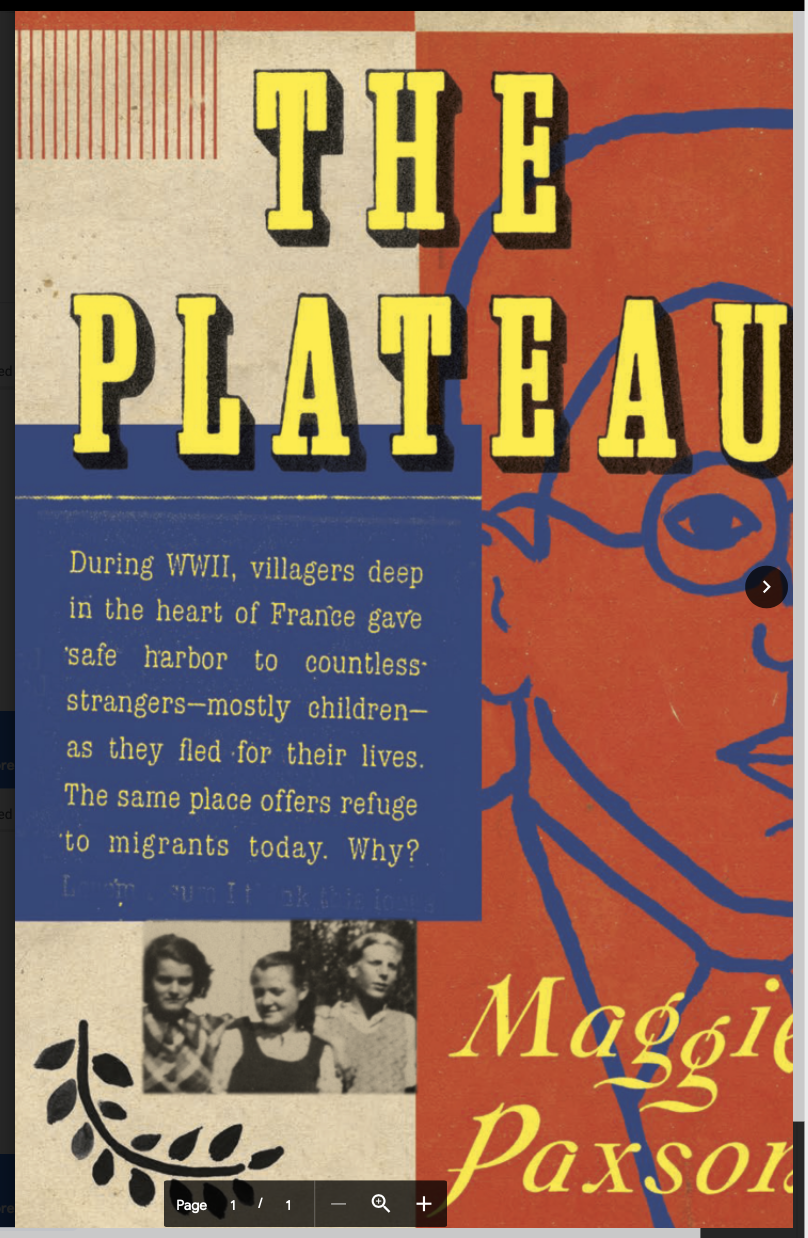

Maggie Paxson is the author of the critically acclaimed The Plateau (Riverhead Books, 2019), which was named a Best Book of the Year by Bookpage and described by the Washington Post as "a loving combination of personal memoir, historical investigation and philosophical meditation." A writer, anthropologist, and performer, she is also the author of Solovyovo (Woodrow Wilson Center/Indiana University Press, 2005), a study of magic, ritual, and social memory in a remote Russian village. Her essays have appeared in Time, Washington Post Magazine, Wilson Quarterly, and Aeon. Fluent in Russian and French, she has worked in rural communities in northern Russia, the Caucasus, and upland France. Paxson holds a B.A. in Anthropology from McGill University, and a M.Sc. and Ph.D. in Anthropology, both from the University of Montreal. She performs as a singer with the Imperial Palms Orchestra, one of the East Coast's leading big bands, featuring music of the 1920s-1940s. She has launched her own series of solo concerts of music from the Second World War–sing-along, participatory events that she calls "The Bomb Shelter Café.” She lives in Washington, DC, with her husband, writer Charles King.

|

|

About The Plateau: During World War II, in a remote pocket of Nazi-held France, villagers offered safe harbor to countless strangers against the threat of mortal danger. Anthropologist Maggie Paxson, certainties shaken by years of studying strife, arrives on the Plateau of Vivarais-Lignon to explore this phenomenon: What are the traits that make a group choose selflessness? Paxson discovers a tradition of offering refuge that dates back centuries but it is the story of a distant relative that provides the beacon for which she has been searching. Restless and idealistic, Daniel Trocmé had found a life of meaning and purpose—or it found him—sheltering a group of children on the Plateau, until the Holocaust came for him, too.

In The Plateau, Paxson blends anthropology, history, and personal introspection while delving into the philosophical and moral issues surrounding peace. The Plateau recently was awarded the 2020 American Library in Paris Book Award. Cheryl Weatherby: Maggie, first off, congratulations on your recent publication of The Plateau. It is a tremendous work and I thank you for your courage and vulnerability.

Throughout The Plateau, you ask, “Who does what with whom?" Why is that question important, and how does it help you build a "model" of how to study peace and the qualities that seem to make for a peaceful community? How has your work challenged assumptions among social scientists about peace studies? Maggie Paxson: When I was a kid, my high school let me take Calculus II at our local university. I loved math so much. I’m not sure if the universe ever felt as orderly and comforting as when I was able to imagine equations emerging into space and time—so brilliant and beautiful. When I started studying anthropology in college, no theory seemed more generative or powerful than even those rudimentary insights that math gave me: Begin a question right at the base of things, with rock solid foundations. Build from there. “Who does what with whom?” is a foundational question. With it, we can clear out our assumptions and see which social groups and categories actually matter in a given place or time. Whom we live with, sleep with, laugh with, buy from, work with; whom we invite over; whose house we sneak into the yard of; whose we don’t dare to. Whom we think of as good or bad or quaint or magical or dangerous or extra beautiful. Because it is such a basic question, there can be surprises—asking it here, there, and everywhere is a way of cleansing the palate of our common sense. The social “circles” or basic mathematical sets I describe are part of this, as well…they allow me to visualize, in the most grounded possible ways, the thing that I was aiming to study. There’s a democratic quality to using such foundational questions—no need for the alienation of jargon when you’re trying to talk with everyone. In the book, the kids at College Cévenol are given these big questions to play with, and they do great. As it perhaps becomes clear to readers, though, these more mathematical constructs and outlines and equations begin to take on a life of their own in the course of The Plateau. They rebel. They are fleshed out. They lose their flesh again. The cover of the book, I thought, was a beautiful echo of that evolution in the case of the face of Daniel Trocmé, in outline. It is a book where he begins as an abstract stranger—an outline of a being—who is shown, over time, in his fuller humanity. Then we see his humanity taken from him. And, in effect, given back. It was similar with the idea about peace. It began as a kind of mathematical problem, where I tried so hard to clear the decks. Then it became thicker and thornier and more than it had been at the start. At the beginning of your book, you describe how people seem to think that peace lacks analyzable “thingness," while war and conflict seem to be events—things that you can count or place into data sets. How did your understandings of peace change over the length of your journey on the plateau? In The Plateau, I grapple with the ideas of great thinkers on nonviolent resistance, like Martin Luther King, Jr., and Gandhi. The core of it for me was this: Every human being is capable of light and dark, good and evil, nobility and depravity, acts of peace and of war. But somewhere, in our deepest places, the light has a special, outsized power. If we listen to the “still small voice” of the light inside us, it will tell us where to go, how to be. It will finally tell us that it is terrible and wrong to let people be murdered for a national idea, to hate them for the color of their skin. It will finally tell us that humanity is, most truly, one. And the arc will bend, then, to its rightful trajectory. The drama of violence is easy to see—a gunshot, a killing, a war. The drama of peace is quieter, deeper, more like the waters that flow underground. This is a book where I had to slow down, turn away from the noise of things, and ask big questions, and then let those questions settle down, and farther down again. In the course of The Plateau, I worked to hone what I was looking for at the heart of a peaceful society—how we take care of one another, how we see strangers as friends. The question that I began with, “What is peace?”—against the backdrop of a violent world—became, in time, “How to be good, when it’s hard to be good?” I could no longer ignore that within the collective ecosystem of a peaceful, thriving world, lie individual souls with individual journeys; and that when those souls are animated by something light and bright together, they become magnetic filaments, all pointing to one direction. There is immense power in the seemingly small person, turning toward the light—toward a true north–together with others, in the aggregate. It can change the world. You weave your personal story line and private moments of pain and transcendence throughout the book’s sections of social science, historical biography, philosophy, and exploration of the sacred. Can you talk about your writing and editing process in relation to this weaving? Did you have a format in mind when you began this massive compilation? If so, in what ways did it evolve over time? And how might your work as a performer and visual artist influenced the form’s complexity? Form followed necessity. When I first outlined the book, I knew that there would be three separate threads: the story of the Plateau (and of Daniel Trocmé) in the past; the story of the Plateau today; the story of my own self—my own mind and heart and soul—wrestling with big matters. This was never going to be a history book. It was always going to be about the world right now, the questions that matter right now. Because of that, each thread was absolutely essential. And each contained realities that were difficult to process: the fact of the Holocaust, the fact of world-sized conflagrations today, the suffering or death of individual loved ones, the fact of moral wobbliness or failure. Each thread had to be woven properly, in order to be kind to the reader. And each thread had its own voice, and each of those voices evolved in the course of the book. Weaving three threads took, basically, every single tool I possessed. I had to figure out how to do it, and that took time. I had to attune my ear very closely to the rhythms of movements, thread to thread to thread, musically. There were leitmotifs of phrases, and even regular onomatopoeic beats. My husband, Charles King, was my first reader, but I wouldn’t let him actually read text—he had to hear me read it all, out loud. I also had to focus hard on the logic of imagery over the logic of arguments (more on that below)—where images recurred and evolved over the course of the book: spiders, lightning, wind, stones. And I developed strategies to help me with all the complexity that no reader in her right mind would notice, like giving the architecture of the book some rules. For example, Daniel’s story and my story were not allowed to meet directly until after the crisis in the middle of the book—I couldn’t have a first-person moment during “his” time until then. There is also the fact that the first and last chapter are rough thematic mirrors to one another, as the second and second to last, etc. That is, the two halves of the book fold up like butterfly wings—where the dead center is a pivotal moment of truth. Reviews have said the book is “genre-melding.” The American Library in Paris called it “an unclassifiable work of anthropology, philosophy, and memory.” Surely, the fact that The Plateau doesn’t fit neatly into a category has meant that some readers will have a harder time finding it. But its complex structure was no caprice. As much as I respect play in all the arts, this wasn’t play. This was necessity. It was both more matter and more art. Regarding the first-person: I had written first-person essays before I embarked on The Plateau, but the first-person was always very small—a pair of (amiable!) eyeballs to help direct readers’ attention. Here, it became clear over time that given the thorniness of the journey, I needed to be more than eyeballs, however amiable; I needed to be a companion, a trusted guide. That was hard because I am generally a pretty private and rather shy person. My editor, Becky Saletan, saw the need for more of “me” before I did, and I’m indebted to her for that, as scary as the process was at times. But I wanted the reader to have her own journey, to get to be brave in her own terms, and ask her own hard questions. How could I expect that from her if I was unwilling to do it myself? Sometimes it was necessary for you to remove your anthropologist’s hat. Can you discuss a few ways in which this role removal helped you to broaden the observations necessary for your research? Right. At a certain point I gave up thinking that I, as a social scientist, could really handle the size and scale of the questions I was asking. That doesn’t mean that other social scientists couldn’t! Just—I knew it was beyond me. I took a deep breath and decided that I would do things differently. I wouldn’t do interviews. I wouldn’t ask directive questions. I stopped bringing my notebooks when I talked with people. I gave up the idea that I might find an “answer” in ways that were acceptable to my field. I wanted to play with kids. I wanted to pitch in in my little ways. I wanted to share meals with the beautiful refugee families and remember my own times of displacement, in their own dimensions. I wanted to empathize with my whole heart and not feel pressure to look like an expert of anything. One interesting artifact of that decision was that I changed entirely how I took notes. For as long as I can remember, I had rituals for that—with the kinds of journals I used, how I recorded a day, how I would make higher order guesses about systems with circles and arrows and the like. Instead, I started drafting what I called “sketches”—from around 500 to 1500 words—about a perplexing or vivid thing that I had witnessed or lived, usually the day before (after sleeping on it). The goal wasn’t to get down everything that had happened—as I had always tried to do in journals—but to try and reach the core of a moment. Many of those sketches ended up seeding the book. Like the spider moment in the car with the family. Or the one where I tell about how I was afraid to go to the forest alone, after the murder of the girl. Or the lightning in Warsaw, and then in Le Chambon. Learning to anchor myself in moments, scenes, poetic logics was a first step to being able to write a book that depended on those. It was a leap of faith. In the writing of The Plateau, there were further consequences of giving up a method. I sensed I needed the book to be structured through images, not through an argument. As I drafted the book, I began to sketch chapters out—I mean, really sketch them, with (primitive!) images of people and animals and landscapes and barbed wire and an outline of Daniel crouched in the corner. Again, it was necessity. Taking off my anthropologist hat meant needing to write differently, too. You discuss how important it is to live a full year in a place to really know it, to experience the harshness of winter there. Would you talk about your relationship to place writing? You describe land and its fragrances, architecture, and weather poetically. Your sensitivity to place and nature are evident in your descriptions of the streets you walked as a child, the Russian villages of your prior field work, and your delight when exploring Israel. How has connection to place influenced your ability to tell the stories you want to tell? My high school English teacher, Ken Wilson, was a displaced southerner who had also lived in India for years as a Peace Corps volunteer. He believed in place, he believed in walking, he believed in knowing the right names for trees and flowers. And those lessons—along with many others—stuck. A couple of micro-lines of poetry that I wrote for his creative writing classes stayed with me all these years and actually found their way into sentences in the first chapter of The Plateau. Then later, the kind of anthropology I studied was one that thought place was important. And seasons were important. I took on the idea that if we “exercise our faculties at large” in spaces—as one of my graduate professors put it, quoting a Robert Duncan poem—we can open ourselves to anything or everything. We can let the universe, in effect, speak to us in its own tongue. It feels like the first step of everything to know where you are. To be quiet and let the air and the trees and the cars and the rust on billboards and the light and shade and the din of others’ speech sink in. To see how people keep their distance, or crowd together. To walk through space, over and over and over again. To be on a train, overland. For The Plateau, I began gathering notes on elements of place: stone, tree, moss, wind, river. Birds. Even when I didn’t know the names for things. I knew they would matter. “Maybe we like to think there’s a kind of trumpet blast that sounds through history, that tells us when it is time to be on the side of the angels. But what if the trumpet doesn’t blast? What if the moments are so small- say, a neighbor who asks to come in even as I pretend not to be at home- that they pass without notice? And what if I am left, then, in terrible times, with my own frailties? Would I be good? Would I be good, after all?” As I read The Plateau, I felt I was witnessing your search for inner peace alongside your search for how to study peace as a contribution to humanity. In your writing, you have masterfully coupled moments of innocence, intimacy, and tenderness next to accounts of violence, chaos, and pain on the faces of those you care deeply for. Did you have a sense of scales and balance with these? Trauma exposure seems inherent to the field work you carried out for years as an anthropologist. If you experienced catharsis in your writing, did it outweigh this compilation's calls to keep revisiting trauma memories during editing and revision? I can say that this subject was very hard for me. But my own difficulty could never, in any universe, compare with how hard it was for the people who lived that period, or for the refugees of today, for that matter. At a certain point, I decided that there was a lot I didn’t know how to do in life, but I could bear witness. And so I needed to try. It is also a matter of faith for me that it makes no sense to write about goodness in a vacuum. The efforts in the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon during the Second World War would seem like common neighborliness if it weren’t for the fact that the world that surrounded that community was in bitter darkness then, and their benign actions put their own lives at great risk. Goodness is brilliant and resplendent when you see it in contrast to the darkness. Like in any painting, the truth of an image comes to life against its backdrop. The writing required me to exercise all the empathy I had, and that was hard—and in the aggregate caused me some of my very own real inner turmoil. But—and this is a big but—it also gave me moments where I felt like I could reach up and feel the transcendent, loving Something out there. Where I was overtaken by the beauty and mystery. Where the community of the Plateau could make me weep with gratitude for its very existence. It’s all of a piece. Taking things on wholly, getting to feel them wholly, even to the point of near-despair. Getting to catch glimpses, even in the peripheral vision, of the grandeur of things. For those of us in whom you have piqued an interest in the non-fiction writing of social scientists, would you recommend a couple books that have inspired you? My own inspiration comes from a lot of places, but rarely from social scientists themselves. This is not because there are no fine writers in that world. But for me, writing feels like an expansive, expressive act—where image, color, and voice matter—and the sweep of sound matters a great deal. So my inspiration comes from some nonfiction writers, yes—especially Antoine de Saint Exupéry (who was, first, a pilot), and Primo Levi (first a chemist)—but also from novelists such as John Steinbeck, where I learned about going from the granular to the grand and back, or Milan Kundera, who showed me how you can shift into idea-speak, and back into poetry. Just what I needed. And yes, poets have been so important—I’ll never get over Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass or Coleman Barks’ translations of Rumi (and the diction of each is probably detectable here and there in The Plateau). And then, yes…music, the development of my very own ear through songs that have haunted me. I don’t think I’ve ever told anyone this, but I especially wanted the very end of my book to be an homage to Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending. And I think it is. Your dedication and honesty have warmed my heart, and I especially loved listening to the audiobook of The Plateau read in your voice. I look forward to your next project! Cheryl Weatherby owns an herbal medicine farm in Harrisburg, Missouri, works as an acupuncturist, and studies graduate non-fiction prose at the University of Missouri. She combines hypnosis and neurolinguistic programming with creative writing as a therapeutic tool for kids

For Further Reading |