The Assay Interview Project: Patrick Madden

July 6, 2016

|

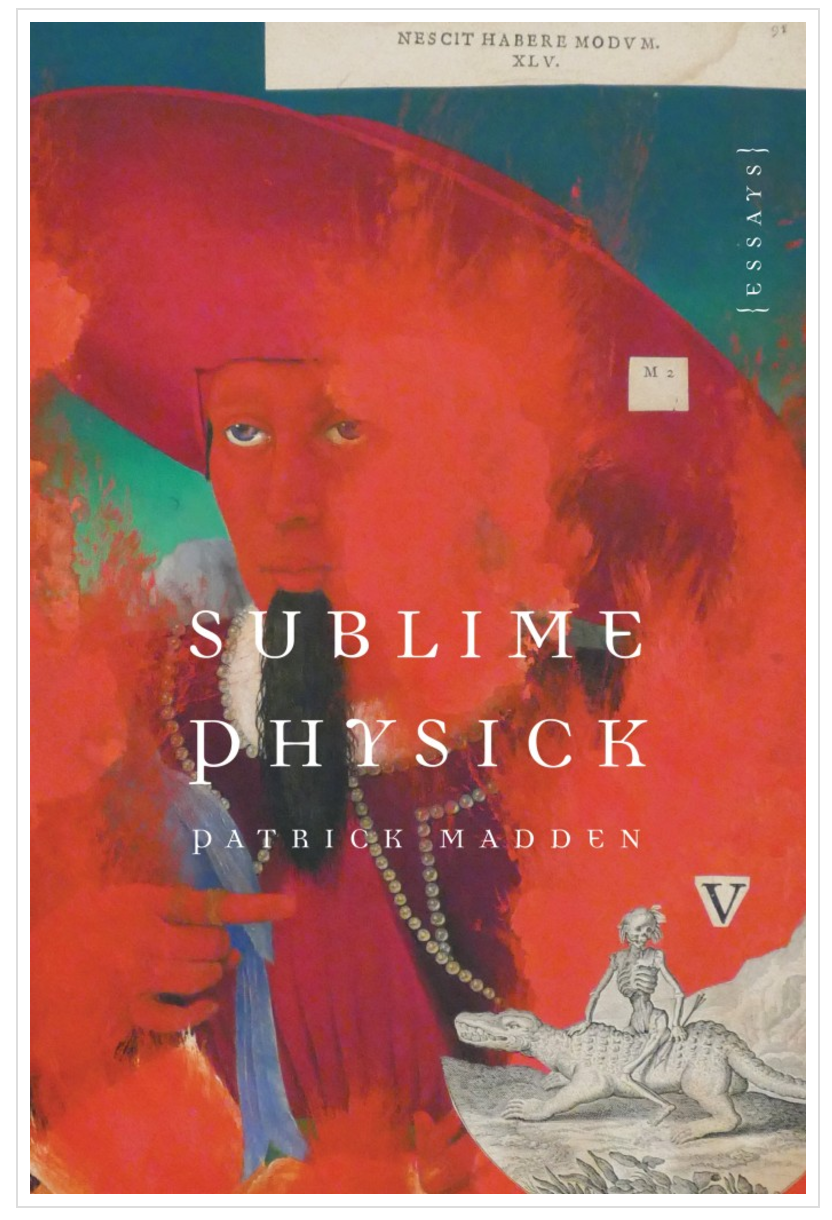

Patrick Madden is the author of Sublime Physick (2016) and Quotidiana (2010), winner of Foreword Reviews and Independent Publisher book of the year awards, and finalist for the PEN Center USA Literary Award. His personal essays, nominated for four Pushcart Prizes and noted in the Best American Essays six times, have been published widely in such journals as Fourth Genre, Hotel Amerika, the Iowa Review, McSweeney’s, the Normal School, River Teeth, and Southwest Review, and have been anthologized in the Best Creative Nonfiction and the Best American Spiritual Writing. With David Lazar, he co-edited After Montaigne: Contemporary Essayists Cover the Essays and now co-edits the 21st Century Essays series at Ohio State University Press. A two-time Fulbright fellow to Uruguay, he teaches at Brigham Young University and Vermont College of Fine Arts, and he curates an online anthology and essay resource at www.quotidiana.org.

|

|

About Sublime Physick: A follow-up to Patrick Madden’s award-winning debut, this introspective and exuberant collection of essays is wide-ranging and wild, following bifurcating paths of thought to surprising connections. In Sublime Physick, Madden seeks what is common and ennobling among seemingly disparate, even divisive, subjects, ruminating on midlife, time, family, forgiveness, loss, originality, a Canadian rock band, and much more, discerning the ways in which the natural world (fisica) transcends and joins the realm of ideas (sublime) through the application of a meditative mind.

In twelve essays that straddle the classical and the contemporary, Madden transmutes the ruder world into a finer one, articulating with subtle humor and playfulness how science and experience abut and intersect with spirituality and everyday life. For teachers who’d like to adopt this book for their classes, Madden has provided a number of helpful teaching resources, including a 40-minute lecture on his writing process and writing prompts for each of the book’s essays. You can find those here. Julija Šukys: First of all, Pat, thank you for this wonderful book. It’s a beautiful, melancholic text, penned, or at least published, at mid-life. We’re almost the same age, you and I, so I connected to the simultaneous gaze backward to childhood, forward to aging and death, and downward to the children at our feet. Tell me a bit about the organizing principle of this book. You write that the “essays all derive, in some way, from the physical world, and all reach, always insufficiently, toward the sublime.” Can you say a little bit more about this?

Patrick Madden: Thanks, Julija. I’m really glad you liked the book. I think that the middle of life (whether “midlife” or not) is a long period of relative stasis (I know I’m oversimplifying), so I hope that these essays can speak to lots of people, in the middle of life. As for the organizing principle of the book: I wanted to collect essays under a general characteristic that holds true not only for my own essays but for essays generally, and I discovered that phrase, sublime physick, while researching Amedeo Avogadro, the 19th-century Italian chemist who theorized that equal volumes of gas contained equal numbers of molecules, no matter the gases. We’ve since named Avogadro’s number (6.02 x 1023, the number of molecules in one mole) after him. Aaanyway, I learned that he held the chair of fisica sublime at the University of Turin. I thought it was a lovely oxymoronic term, because it suggests both the concrete and the abstract, the physical and the sublime. While I realize that this department was the equivalent of our modern-day “theoretical physics” (thinking about the science of the natural world), I played with all sorts of definitions and combinations that give insight into what essays tend to do. So this book collects many essays that have science themes and metaphors (I did my bachelor’s degree in physics), and they all make connections between the world of lived experiences (the concrete) and the world of ideas (the abstract), sometimes with a reach toward the spiritual (or sublime). As you know, I had a group of students read your essay, “Spit,” and the endeavor was wildly successful – my students are still talking about you. In many ways, “Spit” is a classic essay: it combines scene, research and reflection flawlessly. It’s conversational and intimate yet deeply, deeply intellectual, and it vacillates in the most surprising ways between the big and the small. It appears to be about one thing (saliva!) and turns out to be about something else entirely (redemption, forgiveness, self-forgiveness). Tell me about the writing process of this essay. I am smiling. They were a great bunch to talk with, and I’m glad the essay had a good effect on them. I hope one thing they can take from that essay is that they can write about anything, even frivolous or unappealing things, and they can write without knowing from the start where they’re going or what it all means. One night as I was putting my daughters to bed, I realized that one of them was learning to whistle, another was learning to snap her fingers, and the third was learning to ride a bike, and I had a flash of memory to when I learned how to spit. I thought this was an odd thing to remember, especially because I don’t usually have a good memory. So I began to write an essay about spit. It was all very superficial at first: I gathered all the memories and associations I could make with the literal act of expectorating. Of course, I knew that this would never work as an essay. I needed something significant, an idea to explore. I soon remembered what is probably the essay’s climactic moment, when I returned home for a weekend during my freshman year of college and I discovered that one of my friends was now hanging out with a different crowd, doing as they did. I got upset, we argued, and in the escalation of emotions, I spat at him. Because my friend had since died, very young, I began thinking about forgiveness. Beyond that, as I was trying to get some DNA research done on my ancestry (by sending a cheek swab for analysis), I met, through email and phone, a distant relative who’d never known anybody he was genetically related to. Even though our common ancestor lived centuries ago, he was pleased to get to know me. As we shared our experiences, I learned that he’d recently gotten into some legal trouble, so that the life he’d worked so hard to build was falling apart. I began to see him as a tragic hero, undone by his fatal flaw and events beyond his control. This was a challenge to the dear notion that people can repent and change. So I wrote toward this uncomfortable question: What is repentance? How can we forgive? And so forth. I felt that this was a substantial idea at the end of an initially inane essay. Some time ago, I was introduced at a reading as “an essayist,” and immediately felt a sort of revolt inside me that said “No! I’m not an essayist…” A few seconds later, I reversed this and thought, “Hang on, maybe I am an essayist…” It’s been a long road, but for what it’s worth, I increasingly define myself as such. By contrast, you seem to have understood early on exactly what kind of writer you were. In “On Being Recognized,” you quote Arthur Christopher Benson: “The point of the essay is not the subject, for any subject will suffice, but the charm of personality” (117). What is the point of the essay for you, Pat? Can you talk a little about your journey to the essay? Did you flirt with other genres before you settled on this one? Do you ever (as I did recently) get accused of fetishizing the essay? “Fetishizing the essay”! I like that phrase. I’ve never been accused of that, but only (I suppose) because it’s so obvious that I do it. People feel it’s unnecessary to even make the statement about me. Of course, I deny the premise, as “fetishizing” assumes that the obsession is “excessive or irrational,” and this is obviously false. In any case, I never really had any other literary goals, and though I like reading other genres, I’ve never seriously tried writing in them. Joseph Epstein says that essayists are all failed at other literary and artistic pursuits (e.g., Lamb the failed playwright and poet; Hazlitt the failed painter), but this is not the case for me. Unless I’m a failed physicist, I guess. Yes, maybe that’s it. I came to the essay because it promised a great freedom. I had a physics degree, but already before I had graduated I felt the narrowing constraints of lifelong expertise in a very small subject area. In physics, this smallness is doubly true: each physicist’s field is metaphorically small, but also a cutting-edge physicist will probably be working with subatomic particles, invisible even to microscopes, and the work tends to involve colliding accelerated particles then sifting through the computer data for years in order to get a read on what flashed into and out of existence during a nanosecond of interesting results. Aaanyway, I felt claustrophobic at the prospect of dedicating my life to this. Meanwhile, in the two years after graduation, I served a Mormon mission to Uruguay, which gave me a lot of time to think about my future. Gradually I realized that I loved to think wildly, without restraint, flitting from one subject of interest to the next as the spirit moved me. And eventually I discovered or decided that writing essays could be a way to keep my life open and free, to study what subjects inspired me for as long as they inspired me, and then move on. So I came to the essay knowingly, intentionally, and with great hopes. I think now that I was naïve, but also very lucky, so that my life has worked out to be what I had hoped for. By the way, I don’t know who introduced you as an essayist, but I feel that the title is a great compliment. Most people who would use it to describe you would do so knowingly, meaning that you’re an experimenter and explorer. One of my favorite passages in the book came in “Independent Redundancy,” where you announce your very own personal literary invention: the pangram haiku. It takes the standard haiku form (three lines of 5 + 7 + 5 syllables) but it uses every single letter of the alphabet (though not necessarily only once). One of your examples: Lost in flight, quiet Yellow jacket reproves me. Vexed, I buzz away. It’s clear from this essay that you delight in constraints, which was something I didn’t know about you. How can essayists use constraints to their advantage? How have constraints deepened or changed or pushed your writing into new territory? This is a good question on the heels of my answer about choosing essay writing for the great freedoms it allowed me. Do I advance a contradiction when I say that within the thematic and topical freedom of the essay, we might also benefit from somewhat arbitrary constraints upon our writing form? Well, whether it’s negative capability (which idea my friend Paul Westover says Keats probably got from attending a Hazlitt lecture) or simply that the notions don’t quite contradict, I find it acceptable to believe in both. For one thing, we’re all constrained by the language we speak and the words within that language that we know. When I write, I am limiting my audience to those readers who know English, at the very least. But I know what you’re really asking, and, yes, I love to constrain my writing, and the French literary group OuLiPo (workshop of experimental literature) has been a great inspiration for me ever since I learned of them and read some of their work in a class with David Lazar at Ohio University. This is a group of anti-surrealists who made up playful artificial constraints like the lipogram (writing without a particular letter; for instance Georges Perec’s La Disparition, translated as A Void, which omits the letter E). For fun, I’ve written a number of OuLiPian works, and I’ve assigned them to my students as well. And I do think that the Pangram Haiku participates in the spirit of OuLiPo. And they’re still in action! I had lunch with OuLiPo president Paul Fournel a few years back when he came to visit BYU. I even attended his lecture, which he gave in French, which I do not speak or understand. I just sat there smiling, recognizing a few names like Perec and Queneau and Mathews. Most of the constraints I put myself to are not so rigid or obvious, though I do sometimes challenge myself to use a set list of words, for instance, or to sneak in a dozen or so Eddie Money song titles, or to enlist a platoon of clone writers, or… I have fun hiding Easter eggs throughout the book, mostly for my own amusement, I guess. I think, in some sense, writers are always working in hope of some kind of immortality. I know I am. You play with this idea in “Independent Redundancy,” citing posthumous books by David Foster Wallace and W. G. Sebald. You point to prequels penned by the original writer’s heir (Frank Herbert’s son, for example). You write, “I want to keep writing beyond my natural self” (181). How tongue-in-cheek is this declaration? To what extent is making children (yours are so present in this book and elsewhere in your work) a way of “writing” beyond one’s natural self? How do you reach for eternity and immortality through your work? Ha! This is a big question! I will try to answer it. A decade ago, Ian Frazier visited BYU, and I asked him to define literature. With very little hesitation, he said, “Literature wants to be immortal.” He invoked the common journalist’s lament that their work is destined to line bird cages (an idea at least as old as Martial, who says that his writing will wrap tunny fish in the market), and used it in contrast to literary work, which can be timeless, not tied to topics and events of momentary current interest. I waver on this question. I certainly want my writing to be artful and elegant and vibrant with a kind of living voice. And I would like to live on in my writing. I suppose this is somewhat inevitable, since I have children, and they will likely have children, and some of them will want to read what Dad/Grandpa wrote. I would like to be read by others, as well, but I expect not to be. I am only one among thousands of writers living now, one of the obscure writers whose books sell almost entirely to friends of mine. So it’s foolish to expect anything like the immortality of the Great Dead writers we still read. From the Romantic period, a scant 200 years ago, we really only still read two essayists: Lamb and Hazlitt. If we were to select the top two essayists from the early twenty-first century…I’m not sure who they’d be, but they’d certainly not be me. BUT, I did write a brief salutation to the artificially intelligent computers of the future, asking to be revived, and I’m not aware of anyone else who’s done that, so perhaps, once computers rule the world, and they can “read” books instantaneously, they will refind my essays and essentially bring me back to life. I think that will be cool. More seriously, I hold an essentially traditional Christian view of the eternities, and yet I am an essayist, which is to say a doubter and a hedger of bets, so I do in fact see both children and books as alternative pathways to immortality, and since I’ve done some sleuthing to discover nearly forgotten essayists of the past, I can believe that even obscure essays like mine might find readers a hundred or more years from now. I think I would like that very much, though just exactly who “I” would be then, I cannot say. My current self, projecting into the post-self future, likes the idea. And since I write in ways that attempt to translate my actual thoughts into words, I sometime allow myself the naïve fantasy that some of my essence exists in my essays. So why not believe that I can be resurrected through reading in the distant future? Finally, a few thoughts on word counts. “Independent Redundancy” is a long, long, long essay. Here’s what you write on that subject: With this, the last paragraph, I have surpassed thirty thousand words, a silly number of signs to string together under a single heading but a worthy goal nonetheless, as it is approximately the length of Montaigne’s longest essays. . . . I have risked losing the few readers I have, simply for the sake of arbitrariness, yet it was more than this. It was the way the thoughts accreted and would note dissipate. . . the way there is no end to thought. (222) When I read this, my heart sang, because it just so happens that 30,000 words is exactly the count that’s obsessed me since last summer. My newest book (book!) weighed in at a mere 30,000 words when I sent it off to the press in the early fall. I’m not proud of this fact. (Or maybe I am. I’m not sure.) But, between panic attacks and worrying about what I now call “the amazing shrinking book” (I lost 20,000 words in the editing process), I’ve been thinking a lot about form, length, brevity, verbosity, and the weight of a text.

Forgive me the quick request for clarification: so you sent in 30,000 words (which was as-yet incomplete), but then added words to about 50,000, then edited back down to 30,000? I’m a bit confused about how you lost 20,000 words in editing and still wound up with 30,000. Sorry, I’ve gotten ahead of myself: the first draft of my latest book came in at a respectable 50,000 words. But it was clunky and didn’t hang together properly, so last summer, my husband and I did a sort of DIY writers’ retreat. For two weeks, I holed up in a cabin by a lake and worked to reshape the book. In the end, I cut right to the bone. After those two weeks, the book had shrunk from 50,000 to 30,000 words (this is how I ‘lost 20,000 words’). That sliver of a book was the version I sent to the press. My editor had some queries, which I answered, and the book grew somewhat. Now, a year later, I’ve allowed it to regain even more of its fat, so the final version will come in at a still-slender 37,000 words. For a time, I panicked at the book’s brevity, but it turned out that I was worried for no reason. My editor didn’t even blink when I told her (“confessed” might be more accurate) my word count. In your case, since your 30,000 words are one part of a whole, I get the sense that the opposite was true – the essay seemed preposterously long to you. In mine, because they purported to constitute a whole in and of themselves, the same number of “silly signs” (at least initially) felt uncomfortably short. How curious: each of us with our problematic set of 30,000 words. Two sides of the same coin…or something like that. In any case, all that thinking about form and the wholeness of texts rose to the surface as I read “Independent Redundancy.” Of course, a text should only be as long as its subject demands. (We all know this!) But I guess I’m curious to hear (read) you think on the page about form, length and how to know when an essay or a book is done. I love thinking about your questions. I don’t often get this deep into these ideas. Of course, I can’t really answer this. Certainly my opinions won’t hold true for everyone. But I’ll try to think a bit. I guess in a very basic way, a book is a thing with covers and pages with writing or pictures on them. Nowadays, this can be held inside a screened device, and covers and pages can simply be generated images. An essay is an experiment in language exploring an idea or an experience (or several of them). It’s an artistic representation of a mind thinking. It’s a loose sally, a pair of baggy pants, a salad of mixed vegetables and herbs. (I’ve lost the “basic way” I began with.) My 30,000-word essay fits within a book among eleven other essays because I wrote it around the same time I wrote its siblings, and because it takes real-world examples of imitations or plagiarisms or unintentional simultaneous discoveries and thinks on the concept of originality, trying to complicate the simplistic definition we sometimes believe. It’s so long because I kept finding worthy examples of “independent redundancies” that seemed to fit, not only in terms of subject matter, but in the general flow of the essay, which is cumulative, which admits a kind of example-stacking. One of the beautiful things about essays is that in their original form, they were anywhere from 300 to 80,000 words long. Montaigne really ran the gamut of possible lengths, so that really we shouldn’t have any expectation or requirement for essay lengths. As for how to know when an essay or a book is done, I am of two minds (at least). On the one hand, I tend to write over long periods of time and a great many words, and I revise repeatedly, and I feel like I have to achieve an approximation of some Platonic ideal essay, which is always a little better than my actual essay. In this sense, I feel as if my essay exists independently of me, and I’m discovering it as I write. But I also feel like this notion is too mystical, and that a writer is in control of what she writes, and when she stops writing, the essay is done. I’m trying to be pragmatic, or perhaps tautological: it’s done when it’s done. Simple. And on the third hand, I doubt that there’s any kind of transferable, general knowledge about finishing essays, or maybe I’m simply not sophisticated enough to distill any advice about the process. But it seems to me like each essay has its own compositional path, and if I successfully recognize when one essay is finished, that’s no guarantee that I’ll recognize when the next one is finished. Unless, of course, I revert to my second idea: that when I stop writing, it’s done. And finally, finally: I have no question. I only want to note the last image of the book: that of your unborn son Marcos jabbing his elbow to Karina’s belly. The jab restarts life (time) all over again after the loss of your previous baby. It’s a sublime, devastating, and breathtaking image – perfect in its power, truth, and restraint. Congratulations. Thank you so much. I am moved by the fact that you are moved. And I am truly grateful for your thoughtful questions. Julija Šukys is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Missouri, Columbia, where she teaches the writing of creative nonfiction. She is the author of three books, including Siberian Exile: Blood, War, and a Granddaughter’s Reckoning and Epistolophilia: Writing the Life of Ona Šimaite. Epistolophilia won the 2013 Canadian Jewish Book Award for Holocaust Literature.

This interview originally appeared at julijasukys.com. For Further Reading |