The Assay Interview Project: Sonya Bilocerkowycz

January 1, 2021

|

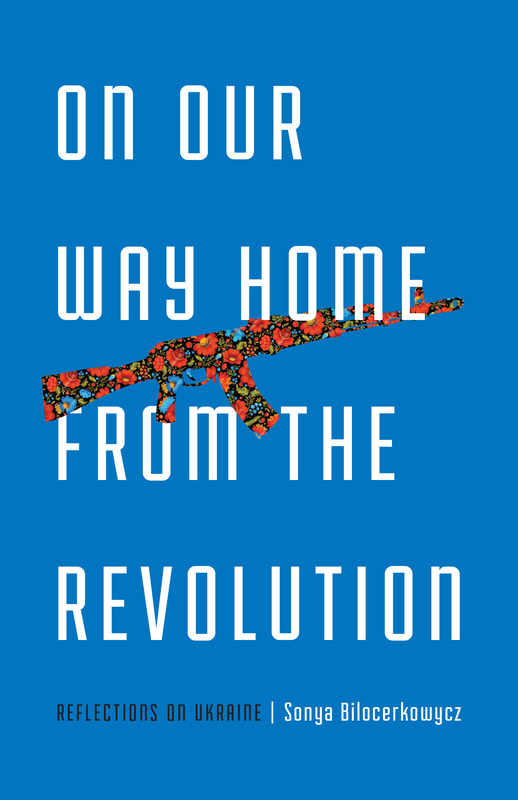

Sonya Bilocerkowycz is the author of On Our Way Home from the Revolution, winner of the 2018 Gournay Prize. Her work has appeared in Lit Hub, Ninth Letter, Image, Colorado Review, Guernica, and elsewhere. Before joining the creative writing faculty at SUNY Geneseo, she served as a Fulbright fellow in Belarus, an educational recruiter in the Republic of Georgia, and an instructor at Ukrainian Catholic University. Sonya is Managing Editor for Speculative Nonfiction.

|

|

About On Our Way Home from the Revolution: Reflections on Ukraine: In 2014, Sonya Bilocerkowycz is a tourist at a deadly revolution. At first, she is enamored with the Ukrainians’ idealism, which reminds her of her own patriotic family. But when the romantic revolution melts into a war with Russia, she becomes disillusioned, prompting a return home to the United States and the diaspora community that raised her.

Through these linked essays, Bilocerkowycz considers her inherited legacy of political oppression. As the daughter of a man who makes his living studying Ukrainian dissidents, the granddaughter of war refugees, and the great-granddaughter of a gulag victim, Bilocerkowycz examines her life in the light of complex political, social, and cultural histories. She invites readers to meet a swirling cast of post-Soviet characters, including a Russian intelligence officer who finds Osama bin Laden a few weeks after 9/11; a Ukrainian poet whose nose gets broken by Russian separatists; and a long-lost relative who drives a bus into the heart of Chernobyl. On Our Way Home from the Revolution is a fiercely honest and empathetic examination of heritage written with poised and unflinching lyricism. Bilocerkowycz’s essays muddle our easy distinctions between innocence and culpability, agency and fate, and leave us with a richer understanding of our own identities and responsibility to our histories. K. Mikey Borgard: This collection weaves a great deal of history into personal and generational narratives. You explore Ukraine’s Maidan revolution and European Union association, the Chechen Wars, the Bolsheviks, the Trump administration’s ties to the region, and many other significant historical events. You weighed the importance of background information and audience awareness when writing these narratives of witnessing and researching. How did you decide what context to give these events?

Sonya Bilocerkowycz: This was a tricky aspect of the composition process. I knew that I would have some readers with considerable knowledge of the post-Soviet space as well as readers with no background in this area, and I wanted the book to be accessible and challenging for both groups. Because I was in an MFA program at Ohio State when I wrote the bulk of these essays, I was attuned to the literary-minded reader who was mostly unfamiliar with this history, and I sought to involve them in it. But there were certain things I knew I didn’t want to compromise on. I included, for example, quite a few Russian and Ukrainian words throughout the text, some with definitions provided, others without. To whatever degree this book required a “translating” of my experiences for non-Ukrainian readers, I suppose I adopted Lawrence Venuti’s concept of foreignization. I wanted to be transparent about the narrator’s ongoing translation efforts. I wanted difference to be perceptible and respected, a recognition of the liminal space the narrator inhabits. And there are essays—like “Encyclopedia of Earthy Things,” which is full of historical references, cultural shorthand, and superstition—that I wrote specifically with a Ukrainian reader in mind. I hope non-Ukrainian readers will take pleasure in the language, imagery, form, etc., but because that essay is about the process of cultural mythmaking, it felt important to explore this concept via the myths of my community. I was also committed to including two essays about Belarus in the collection. Now in its 26th year of dictatorship and with few foreign visitors, Belarus is something of a “black box” on the map of Europe. It’s a humble offering, but perhaps these essays bridging Belarus, Ukraine, and America might cultivate new avenues for connection and understanding. In a few essays, you touch on the notion of belonging to Eastern Europe, of earning the right to connect with the region. The titular essay, for example, identifies you as a “tourist” of the Maidan revolution. Later, in “Duck and Cover,” you paint yourself as disparate from Anna Politkovskaya—a Russian journalist you hold in high regard—as if her contribution to history carries a weight you have not yet defined for your own. How do you view yourself connected to or separated from Ukraine and your Ukrainian heritage? Has your perspective changed since you finished this book? This question was the impetus for the entire book, which I began writing after that experience of being a “tourist” on Maidan. My family was very politically active in Ukrainian causes, and I grew up attending pro-Ukrainian rallies in the US. My first experience of protest, for example, was marching in downtown Chicago in the freezing cold during the Orange Revolution. But when I was on Maidan in 2014, something became obvious to me that wasn’t before, though it certainly should have been: the stakes were not the same for me as they were for my Ukrainian-born relatives and friends. In the middle of this hyper-Ukrainian event, I felt the American part of my identity most acutely. The project, then, became a return “home,” an unpacking of identity and trying to make sense of its contradictions. I suppose my perspective has changed in that I am more comfortable residing within those tensions. In A Stranger’s Journey, David Mura notes that his writing is most energized when in the presence of some threat, when the work calls him to disruptions that may involve “violating community taboos or idealized portraits.” In writing this book, I’ve come to embrace that threat as well. I was very intrigued by the curation of these essays. Some of them, like “Instructions for Parents in Upbringing Children (1950)” and “Article 54 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR (1927 & 1934)” actually come from documents that you reveal later in the collection. What was your organizational process like? What did you hope to achieve by embedding these documents-as-essays before their origins are revealed? Thanks for your attention to these odd little essays! In terms of curation, there were of course considerations of juxtaposition. For example, immediately following “Bloodlines,” an essay about animosity between Ukrainians and Russians, I include the brief essay “Instructions for Parents in Upbringing Children,” which is an actual counterpropaganda document from 1950 that essentially propagandizes Ukrainians for the task of resisting Russian propaganda. (“Don’t trust the Bolsheviks, avoid them at all costs.”) In a sense, this real document acts as supporting evidence for the cultural and familial claims I’m making in the previous essay. I also included these documents-as-essays throughout the first half of the book as a way of building up to the collection’s climax: when the narrator obtains archive papers that implicate her great-grandfather in state violence during the Nazi occupation of Ukraine. The papers were always there, whether we knew to look for them or not, whether we understood them or not. They were there, waiting to be understood. More generally, On Our Way Home from the Revolution presents a range of excerpts from propaganda, samizdat, literature, legal codes, political proclamations, newspapers, etc., and the narrator is continually asking which texts can be trusted and why—including the very text she is writing. At one point she quotes from her father’s book, which notes that “a significant share of dissidents were literati.” I guess you could say the narrator is obsessed with words and their political functions. One of the themes in this collection is fear. Each essay grapples with some kind of fear: generational, political, personal. At times, fear is layered and must be peeled back like an onion, as in your essay “The Village (Reprise).” In this essay, you translate records that implicate your great-grandfather in the deaths of seven people. You fear that your family may be an accessory. You wade through guilt that you say you may not have earned. When you settle into this vulnerability, you write, “What I mean is: the thing we are most afraid of is ourself.” I’m curious about how this theme resonates through this text. How do you understand these personal, raw fears in relation to the larger inherited, political, geographical fears that you depict? Do you believe them to be interconnected or something else entirely? What a great question. I think all these fears are interconnected, and they form a very twisted knot for the narrator. She’s afraid, for example, that President Trump will not step down even if he loses the next election. On its surface, this may seem like a fear that’s pretty far removed from the narrator herself. Trump has vast power and resources; his decisions and maneuvers occur in a realm of global influence so distant from the narrator’s own humble reality. And yet, I would argue that the narrator fears this precisely because she must grapple with the fact that one of her own relatives—a modest village peasant—has been accused of participating in state violence. She is concerned about corruption at the highest levels because she is concerned about it in her own family. She sees the potential for evil in herself, I think, and that refracts upward and outward to other levels of power. Perhaps a certain amount of fear is healthy, but what comes next? The narrator is interested in taking responsibility by disclosing this information about her great-grandfather. I think the book seeks to transform fear into responsibility. You often imagine the United States through the frames of Ukraine, like when you envision Washington, D.C. in miles of barbed-wire barricades in “On Our Way Home from the Revolution.” In “Swing State,” you write, “I read recently that Rachel Crooks, one of the women who accused Donald Trump of sexual assault, won a Democratic primary for the Ohio State Legislature. She decided to enter politics after the man who forcibly kissed her outside an elevator was elected President of the United States. Yes, sometimes an elevator is a war.” A book that explores naturally stops its exploration when it is published. If you could extend the exploration of your writing, if you could offer one takeaway or insight for your readers in 2020, what would it be? That the same nefarious interests at play in the post-Soviet world are at play here in the US. The Belarusian people have been out on the street since August 9, 2020, protesting another election stolen by the dictator. Protestors are facing immense police violence and repressions. As Walter Benjamin writes, police power is an “all-pervasive, ghostly presence in the life of civilized states.” I hope for American readers the same thing I hope for myself: the imagination necessary to view the struggle for liberation in places like Belarus or Ukraine as inextricable from our own liberation. ______________________________________________________________________________ K. Mikey Borgard is a Ph.D. student at the University of Missouri, Columbia, where he specializes in trauma literature and creative writing. He is a survivor of terrorism and has essays published in The Boston Globe and Fourth Genre. |