The Assay Interview Project: Sumana Roy

November 1, 2020

|

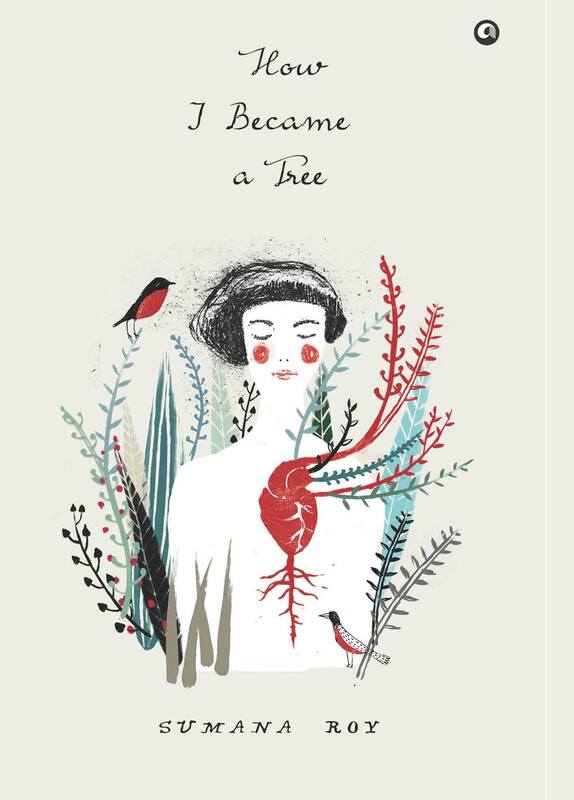

About How I Became A Tree: In this remarkable and often unsettling book, Sumana Roy gives us a new vision of what it means to be human in the natural world. Increasingly disturbed by the violence, hate, insincerity, greed and selfishness of her kind, the author is drawn to the idea of becoming a tree. ‘I was tired of speed’, she writes, ‘I wanted to live to tree time.’ Besides wanting to emulate the spacious, relaxed rhythm of trees, she is drawn to their non-violent ways of being, how they tread lightly upon the earth, their ability to cope with loneliness and pain, the unselfishness with which they give freely of themselves and much more. She gives us new readings of the works of writers, painters, photographers and poets (Rabindranath Tagore and D. H. Lawrence among them) to show how trees and plants have always fascinated us. She studies the work of remarkable scientists like Jagadish Chandra Bose and key spiritual figures like the Buddha to gain even deeper insights into the world of trees. She writes of those who have wondered what it would be like to have sex with a tree, looks into why people marry trees, explores the death and rebirth of trees and tells us why a tree was thought by forest-dwellers to be equal to ten sons.

Mixing memoir, literary history, nature studies, spiritual philosophies and botanical research, How I Became a Tree is a book that will prompt readers to think of themselves and the natural world that they are an intrinsic part of, in fresh ways. It is that rarest of things - A truly original work of art. First things first, if you have loved any of these books— H is for Hawk (Helen Macdonald), The Overstory (Richard Powers), The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating (Elisabeth Tova Bailey), The Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of Consciousness (Sy Montgomery), and All the Wild that Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West (David Gessner) — then, Sumana Roy’s How I Became a Tree is going to be your new favorite.

Second, if you have lived in the West (as in the Western Hemisphere) for as long as I have (14 years and counting), you might have forgotten the legacy of your part of the world. It’s not your fault per se. It’s the constant messaging that surrounds us here. It encourages us to believe that every single breakthrough in human consciousness, art, literature, and science has emanated from here, that other countries have just hung around, twiddling their thumbs, waiting to be rescued and educated, and the only gifts of their culture that count are the ones that can be parceled and consumed in tiny, digestible chunks such as henna and downward dog. And then you chance upon the extraordinary, life-altering essays that make up How I Became a Tree. In page after exquisite page, braiding research, memoir, biography, reportage, and sheer lyricism, Sumana reminds you of everything you have inherited as a citizen of the world—incredible myths, stories, and legends; the work of scientists who are also artists; educators who are also Nobel Prize winning writers; and how sometimes, in order to find community and yourself, you have to step outside your home and family, and seek the company of trees. If, like me, you start following Sumana on social media, here are a few things you might quickly learn about her: that she is deeply in love with her niece and nephew; she takes the most introspective and contemplative photographs, so much so that I think someone should collect them and turn them into a book of writing prompts; and that she is alternately amused and perplexed by her hometown, Siliguri, in northeastern India. Sumana is an Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Ashoka University, and the author of four books: the novel Missing, the short story collection My Mother’s Lovers, the book of poems Out of Syllabus, and my favorite, How I Became a Tree. Her works have also appeared in numerous magazines and journals, including Granta, Guernica, Berfrois, Prairie Schooner, The Bangalore Review, and Cha: An Asian Literary Journal. Sayantani Dasgupta: Thank you for this astonishing book. It is so immersive and richly detailed, it feels like one could have written it only after having lived several lives. How long did you live with the project? Where and how did you even begin?

Sumana Roy: Sayantani, thank you for all the things you’ve said here, and elsewhere. I cannot really say how many years I have spent thinking about becoming a tree. A few days ago, my mother reminded me of something I’d told her in 2004 – about whether it was better to remain a seed, which doesn’t have roots, than to be a tree. I cannot remember saying it to her, but what I do remember is the sadness of that time – my words might have been an unconscious reaching out to an alternate possibility of living? I cannot really say. I might have begun collecting my thoughts in notebooks around 2010 or so – I had a six-hour work commute, and I spent a lot of that time reading, looking outside the window, and writing. None of this was structured to a plan. I was living and struggling to remain alive – I was willing to take anything that would help me sit up, like a twig does to a creeper. I’d finished writing my PhD a few years before that, and I felt free to educate myself in a way that I hadn’t had the chance before. I began reading more literature in Bangla than I ever had, not from any professional ambition, but because it offered me secrecy. I was free of the noise that attends writing in the Anglophone world, and, because I had not been trained or conditioned by Bangla literary history, I could wander in its by-lanes and knock on doors without being intimidated by the critical reputations of writers. I became addicted to two things: my aloneness, and a kind of secrecy, about the withdrawal from the world that I was experiencing. Without my knowledge – and permission, of course – I became someone I hadn’t imagined. I walked all day inside forests, I felt liberated by plant life and my desire to experience it. There was a purity of affection that I might never experience again. SD: My copy of How I Became a Tree is heavily underlined, and I have notes scribbled on every page. Each of your beautifully braided essays touched on so many different subjects and themes. In one essay alone, you could go from discussing the practice of naming women after flowers to the people in Melbourne writing letters to their local trees to the passivity of “sleeping” beauties in fairy tales, the role of trees in Hinduism and Buddhism, to how our lives might look if we lived according to “tree time.” Your tone too goes from meditative to playful to introspective to inquisitive. How did you achieve this multi-layering, and how many drafts did it take you to get there? Whose work did you find useful and influential during the process? SR: Thank you, again, for these kind words. It’s not a ‘style’ that academics take to, and not one that is encouraged, as you know. I would take credit for it if I’d actually arrived at it. The truth is that I didn’t. Retrospectively, looking at it now, as one does at one’s choice of clothes in one’s early adulthood, I can see that it is only an extension of the person I am at various points of time during the day. This wasn’t because I had given permission to myself to write in a certain way. It was the only way I could have written it. I was groping for answers, and I was looking at various archives – the emotional and the intellectual. I suppose the writing reflects that. My problem with staying within the strict boundaries of a particular form and tone – as say, the ‘seriousness’ of academic discourse, where there is no place for humor, in spite of humor being a manifestation of sharpness – is that the person who begins writing is not the same person who finishes writing the essay or the book. How can the writing not reflect or hold that? The draft went through a couple of rounds of editing – first by David Davidar, who asked me to rewrite the concluding section (he wanted it to be shorter), and then by a friend who edited it like only a friend can. SD: One anecdote I especially enjoyed was when you brought home a large, dead tree from the side of the road. What was your family’s reaction? And do you still do that? SR: At the moment there are three large trees inside the house – one in the bedroom, another in the living room, the third on a stair landing. When I found them, they were already dead – one on the highway, the other two near a church close to our house. They were heavy, as I imagine the dead become. I had to find allies to get them to the house. Then there was Bimal da, the carpenter, who I requested for help. Brahminical about the ‘worth’ of wood, he declined having anything to do with them – ‘Ku-kaath,’ he said, ‘bad wood’. I told him that I hadn’t got them home for their wood, but because I didn’t want them to be left dying without dignity. He gave them stilts, and that is how they still stand. Do I still do that? Oh yes. There’s a beautiful tree trunk lying by the roadside near what used to be Chandmoni Tea Estate. I’d have tried to get it home had there been no restrictions of the kind created by Covid-19. I should add that I feel no missionary zeal about this. It is my selfishness – I’d like them to be home with me. There are old roots of several tea shrubs in the house. They are not furniture. They are residents. SD: There is so much research in this book. Of course, thanks to your gorgeous writing, at no point it feels like research per se but as if we are in the midst of the best TED talk, where a funny anecdote follows a striking observation or a thoughtful question. Research forms an essential component of my writing as well, which is perhaps why I am curious. How do you go about researching? And what role would you say research plays in your work overall, irrespective of the language and the genre? SR: The ‘research’ – and you know why I’m using the word in quotes – for How I Became a Tree began from myself. Who was this person, this person that was me? And then the centrifugality – were there other people like me who had felt a similar urge to become a tree, to live the tree life? Some of this came to me from what I’d read years ago, except that I hadn’t seen it then. One such writer was Rabindranath Tagore. Some chose themselves: the scientist Jagadish Chandra Bose, whose exciting and experimental work on plant life gives me goosebumps; the Buddha, whose teachings I have been trying to understand for decades now. I asked a few people, friends I could trust not just with their knowledge, but also those who would not judge the rather unexpected question: ‘Do you know of people who wanted to become a tree?’ One person whose support I must mention here is the historian Chandak Sengoopta. He directed me towards texts in Bangla, and often pointed out idiomatic usage about plant life to me in short messages on Messenger. Sometimes just a casual conversation with old classmates would lead me to a story or a news report. That was my ‘research’. I have now come to accept that research in the academic sense of the word is not for me – it doesn’t agree with my temperament, and, more importantly, it doesn’t agree with my body. Whatever comes to me from life I gather – I am a hunter-gatherer more than a digger. SD: Another of my favorite things about How I Became a Tree is looking at the world through your gaze. Curiosity and wonder are very close to my heart, both as a writer and a person, and your writing is exactly what I need from a book of creative nonfiction. How do you keep those senses heightened? How do you encourage your students to develop that gaze with respect to their own work and research? SR: I wish I could take credit for it, Sayantani, but this is just how I am, I suppose. Love for a person comes to me from a sense of wonder too, as does curiosity – I want to know more about the person because I find him so interesting. That is also how I experience other things in the world, and that also restricts my understanding and experience of the world – the things and people and spaces that do not evoke my wonder become uninteresting for me. You mention the senses – the senses are my point of entry into a text, literary or otherwise. I must experience the things I am writing about with not just my mind – wherever its location might be – but also through my senses and my emotions. It's hard – and perhaps wrong – to force my understanding on my students. What I do emphasize is honesty, by which I do not mean a moral category, but something practical: to write about what one has experienced, no matter what the genre of their choice. No ‘theory’ can take the place of living. SD: I am so intrigued by one character in particular -- your paternal grandmother. Why did she crush a red hibiscus between the pages of her husband’s ledgers every day of her married life? SR: I hardly got to know her. She lived in the village – she was quiet and hardworking and stubborn in her resistance to things. I remember the ‘thakur ghar’ – as a child I thought it a doll’s house. I now think of it as her paracosm. I cannot remember my grandparents speaking to each other except indirectly, and never with intimacy or affection. My paternal grandfather was a businessman who had done well for himself after coming from Bangladesh a few days before 15th August 1947. He had the pride of the self-made man – this manifested itself as domination in the most unjustifiable ways. I think of that act of crushing a red hibiscus between the pages of her husband’s ledgers as her show of anger. Women have had to create an alternate vocabulary to be able to express their emotions, as you know – particularly of anger, annoyance and frustration. That she chose to do this with a flower she used to worship her gods I, like you, found striking. SD: Did you ever worry that the subject might not be “popular” or “accessible,” whether with audiences in South Asia or in the West? I ask because I come across students, as well as writers outside of my teaching life, who have read the latest “it” book (irrespective of the genre), and worry their writing must align with that in order for it to be published. SR: How I Became a Tree has not been published in the UK and the US. The rejection emails offer exactly this as the reason – that the examples I give would be ‘unfamiliar’ to readers in these cultures and countries. It has just been published in France and Germany – the publishers (Gallimard; Matthes and Seitz Berlin) have told me that the responses have fortunately not been about this imagined ‘unfamiliarity’ with writers and texts that I discuss. As you know Sayantani, this owes to a circuit of power – the Indian reader sitting in Siliguri must not be worried about not knowing the taste of doughnuts when they read about New York, but no, the American reader must be told what the litti is all about. It is an infantilization of the ‘Western’ reader that is hilarious and hierarchical. We must always explain ourselves – we’re always waiting at the immigration queue, for some kind of clearance or the other. That is why our literature must be Area Studies or a version of Festival of India. We are writers of handbooks of our cultures. Amit Chaudhuri, in his essay “I am Ramu” (published in n plus one) writes, ‘The important European novelist makes innovations in the form; the important Indian novelist writes about India. This is a generalization, and not one that I believe. But it represents an unexpressed attitude that governs some of the ways we think of literature today. …The American writer has succeeded the European writer. The rest of us write of where we come from.’ I will confess that much as I might like to be read by Americans, I cannot write in any other way or about any other thing that might happen to be sexy at the moment. It is not because I am arrogant, but because of my inability to write in any other way than what I do now. Even if I tried, the dishonesty and my lack of interest would show. No one would want to read the book, not even me. SD: Please walk us through your entire process of writing an essay, if you can. Once the idea germinates, do you write out an entire draft in one go? Do you develop it over time? Do you have a writing group that reads each other’s work and offers comments or does your work go straight from your computer to an editor’s? SR: I don’t have a writing group, Sayantani. My old nervousness about sharing my writing – and the secrecy that attends it, a habit from the time I kept my writing a secret from my family, who thought I was working on my PhD – remains. I am able to share it with only my closest friend, who is always kind enough to edit it. I then send it out. My desire for feedback is strangely very low – I also don’t read reviews (I stopped after reading the first few reviews of How I Became a Tree – I feel nervous, like I did in front of teachers in school). It might come from the need to protect myself – I am shy too, and asking for someone’s time to read and offer feedback is difficult for me to do. Having said all of this, I must add something that would be uncharacteristic for such a person – I love being edited. And I have complete faith in my editor. Let me try to answer your question about the life of the essay as honestly as I can. I am thinking back to some of the essays I have written recently. I think the essay is different from the lyric poem in this way – it is not impulsive. I can’t elope with the essay the way I can with a poem. I am trying to think – the idea for the essay comes from affection or annoyance, and it stays with me for months, often years, until it begins to come out of me in spurts. Quite often I hear it – the voice saying it. I begin writing. Only very rarely am I able to complete the essay in a day or two – then it’s like a spell, and I write as if there was no way to be disobedient to that voice. But mostly it spreads out over a period of time. I write other things – and other essays – at the same time. It grows as I grow older. I read something, it enters the essay as some kind of response, however tangential; I am hurt, I cry, that too enters the essay, as some form of questioning of my love; I am frustrated with the nature of my day, that will enter the essay too. It becomes a relationship, and then it ends, almost suddenly. The essay is done. I like the freedom of the essay as a form – it allows me more asides than any other form does. And, as anyone who has managed to survive my digressions in real life will tell you, no other relationship will possibly allow that. SD: You write fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction, and you write in both English and Bangla. What do you steal or borrow from each genre when you are writing the other? Are you a different writer in these two different languages? Do you think differently? I ask because I dream in Bangla, consume most of my entertainment in Hindi, but write in English. SR: I don’t write in Bangla, Sayantani – a regret, a real regret. I try to write Bangla in English – the beauty of Bengali, its sound and its script, the poets who have constantly refreshed and reinvented the language, the ‘shondhi’ sounds engineered by the Bengali imagination, bringing in multiple senses and histories and weather, all of these I’d like to import to my English. I fail, of course, as such desires are meant to. About genre, I am unable to make any distinction. None of us sets out to write a story or a poem or an essay. It is not like filling up an immigration form, after all. They come to me without my interference – sometimes as a poem, or an essay, and so on. These are public names – the names of these genres. I suppose I am on nickname-terms with them – by which I mean that their names are dependent on the immediate relationships that I am sharing with them at that moment. It is like the different names we have for a loved one. I also rely on what Michel Serres says in Five Senses – about one sense never being privileged over another, and how that is changed when it comes to the question of genre, where there is a heightening of one sense over the rest. I want to meet the text directly, without being told what it is. Just as I wouldn’t like anyone to tell me about the kind of person Sayantani is before I meet you, similarly with the text I want to read. SD: I remember a social media post where you had talked about your students imitating the structure of the Hanuman Chalisa, the 40-verse, devotional poem from 16th century India. As a professor of creative writing, in what other ways have you decolonized the curriculum, and what’s been your students’ reaction? SR: Thank you for this question, Sayantani. For the first fourteen years of my life as a teacher, I had no say in what I’d have to teach my students. The syllabus was set by a centralized group of ‘experts’, and though it underwent some kind of moulting a couple of times every decade, it paid no heed to the varying backgrounds and expectations of the students studying for the undergrad degree. When I first began teaching the poetry workshop at Ashoka University, I was nervous and unprepared. Saikat Majumdar, who heads the Creative Writing program there, had asked me to teach it after reading my poems. He’d placed trust in my ability to articulate what it was that was making me write the kind of poems that I had been. I was a student and teacher of what continues to be called ‘English Literature’ in India. I had no experience of the CW classroom or the MFA program. It was then, while designing the syllabus for the poetry workshop – though ‘designing’ sounds far too fancy and inaccurate a word for the kind of groping that I have been doing – that I decided, almost purely from a sense of instinct rather than formal education or directed by political correctness, that I’d like to read as many kinds and forms and sub-genres of the poem from non-Anglophone cultures, particularly those in India, with my students. I still remember my nervousness in the first class. I wanted to tell my students that I would not be able to ‘teach’ them how to write poems, but I would try to make them better readers of the poem, both their own work and that of strangers. To do so, I gave them the easiest analogy that came to me: to be an efficient singer, you had to be an attentive listener. I used the word ‘sruti’, the word that gives spine to ‘srota’, listener. ‘Sruti’, standing roughly for what was heard, was actually a knowledge system that had been pushed to the back of our consciousness because of the privileging of the written word over the oral tradition. None of my students responded to the word. They were unfamiliar with its sound. All of them were talented, as I could see in their writing, but their understanding of art and themselves had been formed by a monological Anglophone imagination. My resolve to change that grew stronger over that summer. Apart from reading poems in translation from various linguistic cultures, I decided to make them think about the forms that we were surrounded by: the Lokkhir panchali, the Hanuman chalisa, the ghazal, the rekhti, the refrain and incantatory nature of the mantra, among other forms. The Found poems that we read were often bilingual – words from neighbouring languages, Marathi and Telegu, for instance, lived alongside English in them. Sayantani, I will share with you something that is perhaps completely outrageous – it is my suspicion of the straight line, and my intuitive understanding of it belonging to a colonizing mission. It is perhaps still too early to share this with my students, but I’d like my students to be aware of, and then liberated of, the hegemony of the straight line, of the understanding of the ‘line’ in a poem. SD: In an interview with the Deccan Chronicle, you mentioned that you came to writing late, and so you have to work harder at it than those to whom writing might come easily and more naturally. I am one of those people who has been writing since I was six-years-old. At the same time, I am thrilled when someone falls in love with writing later in life, whether as a full-time profession or a hobby. There is almost a deeper, prayer-like quality to that love. What do you tell friends, acquaintances, and peers who may look at writing contests and opportunities that celebrate youth—all the 25 under 25 contests—and feel disheartened? What do you tell your students who may feel the pressure to publish their first book as soon as they graduate? SR: I came to writing very late in my life. Yes, I’ve shared this before – that my middleclass upbringing in a small town did not allow me to imagine the life of a writer. It was perhaps also because I did not know a single writer in Siliguri then. I can now see that reading is also a form of writing, but I did not have that understanding then. I was homesick for Bangla, the language of my living, and I wanted to return to it after the day’s reading for my PhD. It was then that I began writing – not in Bangla, a language I wish I could write in, but trying to write Bangla in English, an ambition and desire I retain to this day. We live in an ageist culture – women have suffered for this in several ways, to do with self-esteem related to their bodies of course, but also in the kind of opportunities they have allowed themselves to take. Women often come to writing after years devoted only to their families. And, quite often, people, irrespective of gender, find the confidence and even the subject material for their writing only in middle age. Under 25/30/35 lists are discriminatory – it is in the genes of lists to be discriminatory. I would tell everyone – including my students – to not bother about lists at all. Yes, there are professional compulsions about publishing early, related as it has become to getting jobs, and so on, but most people cannot afford the luxury of being full-time writers. And so I’d ask them to do justice to themselves and their work by giving it the time to grow, as I imagine books once did, books that stayed with us, books that we did not discover on any list. Anything linked to age is depressive and repressive, I think. Aging takes us closer to what we want to avoid as long as we can – death. To link writing and what is called ‘productivity’ to this limited understanding of time is a function of capitalism that we, as writers, have come to accept without protest. SD: And finally, the dreaded question: what are you working on next? SR: Arvind Krishna Mehrotra has a poem that has the title “Where Will the Next One Come From”. Most of the poem is now hidden from my memory, but it is impossible to forget the intelligence and the humor and vulnerability of the words in the title. Unlike the other things that come out of us – spit and snot and shit and sweat, for instance – we cannot be certain about the writing or art that will break out of us. I have been thinking and trying to write about the provincial reader, in India but also elsewhere. It began from a place of confusion – I do not understand much of what passes for ‘academic discourse’ in the Humanities and Social Sciences in India, particularly in its provinces, today. I wanted to understand how we got here – my teachers in college spoke and wrote differently. Gradually my interest has spread to other places where the use of the English language has its own peculiarities and hidden histories. This has also made me look at the singer and actor Kishore Kumar in a way I had never anticipated. So – I’m not sure about what I am really working on, but there are the little joys of these discoveries that I have been savoring in these home-bound times, Sayantani. An alumna of St. Stephen’s College and JNU, Contributing Editor Sayantani Dasgupta has an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Idaho. She is the author of Fire Girl: Essays on India, America, & the In-Between—a Finalist for the Foreword Indies Awards for Creative Nonfiction—and the chapbook The House of Nails: Memories of a New Delhi Childhood. Her essays and short stories have appeared in The Hindu, The Rumpus, Scroll, Economic & Political Weekly, IIC Quarterly, Chicago Quarterly Review, and others. She is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at the University of North Carolina-Wilmington, and has also taught in India, Italy, and Mexico.

For Further Reading |