The Assay Interview Project: Victoria Chang

January 31, 2022

|

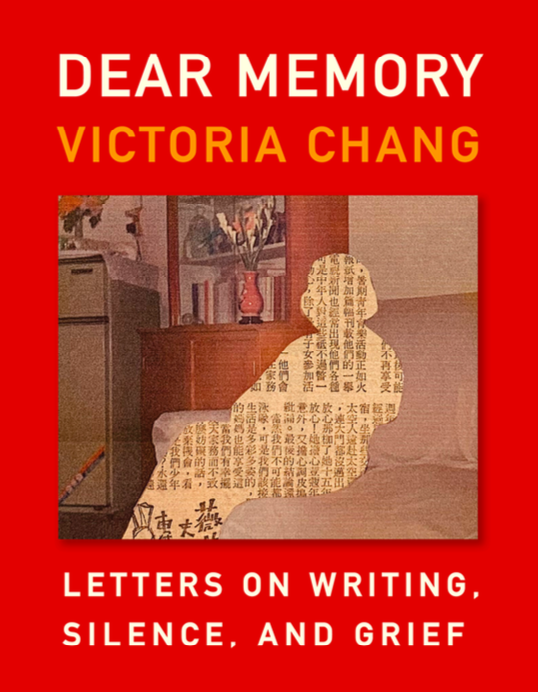

Victoria Chang’s latest poetry book is OBIT, which was named a New York Times Notable Book, a TIME Best Book of the Year, and received the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, and the PEN Voelcker Award. It was also longlisted for a National Book Award and named a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Griffin International Poetry Prize. Her forthcoming hybrid nonfiction book is Dear Memory. Other poetry books are Barbie Chang, The Boss, Salvinia Molesta, and Circle. Her children’s books are middle grade novel, Love, Love and picture book, Is Mommy? which was named a New York Times Notable Book. She has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Sustainable Arts Foundation Fellowship, the Poetry Society of America’s Alice Fay Di Castagnola Award, a Pushcart Prize, a Lannan Residency Fellowship, and a Katherine Min MacDowell Colony Fellowship. Her poems have been published in Best American Poetry. She lives in Los Angeles and serves as the Program Chair of Antioch’s MFA Program.

|

|

About Dear Memory: For Victoria Chang, memory “isn’t something that blooms, but something that bleeds internally.” It is willed, summoned, and dragged to the surface. The remembrances in this collection of letters are founded in the fragments of stories her mother shared reluctantly, and the silences of her father, who first would not and then could not share more. They are whittled and sculpted from an archive of family relics: a marriage license, a letter, a visa petition, a photograph. And, just as often, they are built on the questions that can no longer be answered.

Dear Memory is not a transcription but a process of simultaneously shaping and being shaped, knowing that when a writer dips their pen into history, what emerges is poetry. In carefully crafted collages and missives on trauma, loss, and Americanness, Victoria Chang grasps on to a sense of self that grief threatens to dissipate. In letters to family, past teachers, and fellow poets, as the imagination, Dear Memory offers a model for what it looks like to find ourselves in our histories. Phong Nguyen: I am in awe of how intensely personal Dear Memory gets. It confronts deep familial issues both past and present. I know that so much more went into this book than mere “courage,” but I must ask because of my own fear of soul-baring: How did you muster the will to write about such vulnerable subjects?

Victoria Chang: This is a good question. I always tell my students just to write everything down first without thinking about audience or readers. Just write and be honest and authentic and then you can always delete everything later if you want. I think I tend to overshare in my first drafts and then have to go in and change a lot, but that process of being honest is a useful one for me as a writer, human, and thinker. I think I learn something from that process--I'm working through things as I go. I also believe that there are enough masks in the world as it is. We're always performing something so maybe for just a little while, I can not perform and just write what I feel/think. Some of the artifacts and documents you use in the book are relatively unchanged; others appear significantly changed from the originals (with text layered over them, faces cut out, etc). What guided your choice as to how, and to what extent, you were going to alter the artifacts and documents that you used in the book? Much of the making of this book was organic. What you ended up seeing was the process, meaning, you can see inside the body of the book, all of its organs and bones. I had no intention to make this book at all, so I had no preconceived notions of what this book would be which I think feels a little apparent in the outcome. It's a bit of a mish-mash of many things. The same is true with the artifacts and art. I made them alongside editing the letters, perhaps later in the process of writing. They started out as clip-artish type of art, but really changed over time. I'm not a visual artist by training, and that shows, but I think I did my best. Mostly, the art interacts with the text and vice versa. Early in the book, you ask: “Can I be the hawk and the storm that tries to kill the hawk? Am I willing to write about the dead?” This quote leads me to something I’ve often had occasion to think about: How does one represent the stories of those who cannot represent themselves? It sounds heroic in the abstract, but whenever I try to, say, write my father’s story, it feels appropriative or inauthentic. Do you feel you have to overcome a sense of appropriation or inauthenticity? Great question. This is a really hard one. There's a reason why this book has come out after my mother is no longer here and long after my father lost his ability to read or communicate. The act of writing is ultimately about writing our own perspectives but it doesn't mean that, in the process, you might not harm someone else. But at the end of the day, as writers and artists, we have to make that choice. If we don't write, we are silencing ourselves and our perspectives. I think the most important thing to know is that others will react to your writing, particularly if it is about them. But we have to write to survive as artists and so the way to do that is to write with as much integrity as possible and respect for oneself and others. And then after that, there's not much we can do. We can't control how others think or feel. In the context of American Chinese food served at Chinese restaurants, you write that “we perpetuate our own stereotypes, our own vanishing.” Assimilation is often associated with erasure in literature, especially Asian American Literature. For you, is assimilation always erasure, or are there less insidious versions of assimilation? I am so tired of that word, assimilation, because I have thought about it my whole life and have tried to assimilate everywhere I have gone (mostly unsuccessfully). So at this point, I don't want to do it anymore. I think in this way, the assimilation that I enacted helped me in all sorts of settings. I still do it all the time, though, honestly. But I think we all do–what is "professionalism" anyway? It's a form of assimilation. It's also a form of survival. And survival means one can get paid for being professional, feed oneself, and then use that money to make art. I just think each person needs to figure out how much to assimilate and when and why, and when to refuse assimilation for self respect or self preservation. Like everything, it's complicated. “Poets live between a fire and a great fire” is such a potent and memorable line. Is it something that all poets understand? How would you explain this revelation to non-poets? Poets hate explaining things! Because I think a lot of times, we're writing tones, not ideas, auras versus arguments. I'm not sure what this means exactly, to be honest. It just felt like a way to describe that kind of weird place that poets live in, that really vibrant yet slightly hellish space that poets emotionally live in, or maybe all artists. I think this books is obviously prose but once in a while, it feels poetic, meaning, it's hard to write anything without being a poet. You quote Winterson as saying that “the best work speaks intimately to you even though it has been consciously made to speak intimately to thousands of others.” How do you conceive of your audience when you write? And how do you think Winterson’s ideal of a work that “speaks intimately to you” is achieved? I think about this a lot, especially when I'm writing autobiographical material or into autobiographical material. At some point, I wonder why anyone would care about anything I'm writing about so I think a lot in general about making art versus telling a personal story. This is not to say that personal stories can't be art, but sometimes I think they get a little too involved in their own selfness and/or their own reality. I suppose the question is how to make art that is both incredibly intimate but also expansive? That's the big question for me when I'm writing anything, whether poetry or nonfiction or fiction. I think for other people, they might have different questions, but I think this is one of my big artistic questions. But perhaps I'm a writer of paradoxes--I'm interested in the micro and the macro, the personal and the collective, etc. The question of whether “a writer needs to suffer”: is there an answer? There are always answers! Or maybe responses is a better word. The older I get, the more I wonder whether everyone suffers in our own ways throughout life. If we live long enough, we will all suffer a lot, meaning we will all watch/witness parents dying, pets dying, the catastrophes and injustices of the world. I don't know if that suffering needs to be made into art, though, or whether that suffering makes the artist a more expansively human individual who then can make art that transmits to others in a way that is more resonant. So "needs" is probably not true, but maybe a writer "will" suffer and that suffering "may" make the work more interesting if we lean into it and listen to the suffering. Phong Nguyen is the author of three novels, The Bronze Drum (Grand Central Publishing, 2022), Roundabout: An Improvisational Fiction (Moon City Press, 2020) and The Adventures of Joe Harper (Outpost19, 2016), winner of the Prairie Heritage Book Award; and two story collections: Pages from the Textbook of Alternate History (C&R Press, 2019) and Memory Sickness and Other Stories (Elixir Press, 2011), winner of the Elixir Press Fiction Prize. He is co-editor, with Dan Chaon and Norah Lind, of the book Nancy Hale: On the Life & Work of a Lost American Master (Pleiades Press/LSU Press, 2012), part of the Unsung Masters Series. He is series editor for the Best Peace Fiction anthology (University of New Mexico Press). He served as chief editor and fiction editor for Pleiades: Literature in Context for eleven years, during which time he published the early work of some of the most celebrated fiction-writers of the last decade: Bonnie Jo Campbell, Amina Gautier, Zachary Mason, Christine Sneed, Alexander Weinstein, Tiphanie Yanique, and many others. He has worked as chief editor for Cream City Review for three years, and as an editorial intern for The Atlantic Monthly. His own stories have appeared in more than 50 national literary journals and anthologies, including Agni, Boulevard, Chattahoochee Review, Iowa Review, Massachusetts Review, Mississippi Review, Ninth Letter, North American Review, PANK, Prairie Schooner, River Styx, and Texas Review.

For Further Reading |